How one couple’s collection beckons us to appreciate our common humanity

When I suggested it would take a year to tell me about every artifact or piece of art in his home, Bill Hohulin laughed but didn’t correct me. A year is a generous estimate—not only because of the sheer volume of treasures he and his wife own, but because each prompts a rich story of its procurement… and the valuable history of its function before it was theirs.

Discovering the World

Married for 57 years, Bill and Lydia Hohulin live in Goodfield, Illinois, in a home with floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking a forested backyard that slopes toward the Mackinaw River. The house—like its many tile murals, quaint nooks and outdoor courtyards—was designed and built by Bill, who briefly studied architecture before pursuing a degree in education.

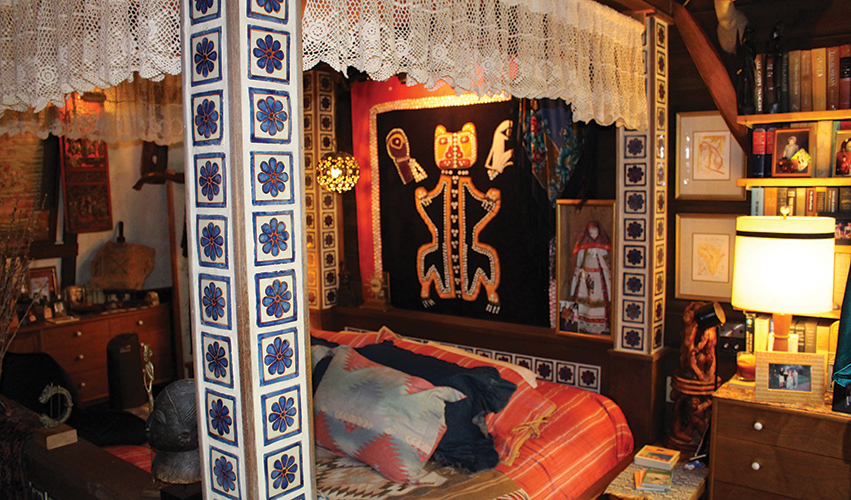

As retired schoolteachers, Bill and Lydia have a shared interest in artifacts that can help educate people about our world’s many diverse cultures. Their home resembles a museum: an aesthetic banquet of unlikely oddities. “We want to give people accurate and respectful information about other cultures’ religions and traditions,” Lydia explains, leaning against a pillow made of colorful wedding saris from the state of Gujarat, India. “The artifacts help us to do that.”

In a living room which houses rare, handmade string instruments, a Tibetan spire and a prominent zebra hide, among various other curios, Bill talks about his first interaction with collecting as a nine-year-old boy. That summer, he was confined to a dark room as doctors tried to recover the sight he had lost in one eye. With little else to do, he began saving stamps from the envelopes of the many cards he received, enthralled by the geography and cultures they represented.

In a living room which houses rare, handmade string instruments, a Tibetan spire and a prominent zebra hide, among various other curios, Bill talks about his first interaction with collecting as a nine-year-old boy. That summer, he was confined to a dark room as doctors tried to recover the sight he had lost in one eye. With little else to do, he began saving stamps from the envelopes of the many cards he received, enthralled by the geography and cultures they represented.

“I traveled the world vicariously,” Bill remembers. As he grew older, the horizons of his gathering expanded. He and Lydia agree that the beginnings of their mutual interest in artifacts expanded from the couple’s initial collection of authorized prints by 19th- and 20th-century artists. The collection, which includes works by Picasso, Miró, Chagall and Dali, is displayed behind a credenza topped with glass decanters of aged liquor, sparkling in the light of a low-hanging, beaded chandelier.

The couple speaks convincingly of these artists’ depictions of primitive objects and the worldviews they represent. By transferring the various artifacts brought to Europe during the colonization and exploration of Africa and the Far East into cubist or surrealist paintings, they helped influence Western understanding of the people of the world.

From her living-room seat, Lydia motions toward a collection of what appear to be African tribal masks displayed in columns on a nearby wall. “The way [they] went with the whole movement of modern art is totally an amazing study in itself. To know people by how they mask.”

Cultural Reflections

The way the Hohulins interact with their artifacts, however, is fundamentally different; they are much more interested in accuracy. From the global reaches of stamp collecting to the indigenous aesthetics of tribal masks, Bill and Lydia were led to the desire to gather artifacts as a reflection of culture. Unlike the turn-of-the-century artists they were drawn to—whose cultural representations might be muddled or figurative—the Hohulins aim to use artifacts to teach about real traditions, religions and events around the globe.

“Does it have aesthetic value? Does it have historical value? How does it fit into that whole realm that we’re trying to portray to our students?” These are the questions Lydia asks before any purchase.

A couple hundred years before these modern artists came along, natural artifacts from around the world were collected in Renaissance-era “cabinets of curiosities.” The houseguests of wealthy collectors would marvel at the flora and fauna being unearthed in places Europeans were discovering for the first time. These objects were often utilized as props to tell stories of an exotic and mystical nature—like narwhal whale tusks that were said to be magical unicorn horns.

While the objects in these cabinets of curiosities were subject to interpretation—at times belittling or exoticizing the cultures from which they came—they also broadened the viewers’ understanding of the world. The Hohulins’ own modern-day cabinet of curiosities might conjure comparisons to this cultural pilfering, if the intentions behind it are misjudged. But the way they present their objects, with respectful appreciation rather than mystical storytelling, promotes a helpful curiosity in a modern world torn apart by divergent ideologies.

Sharing Their Treasures

I ask if the couple would show me three of their most treasured items; they each pick one and agree on one more. Lydia selects a French provincial clock, standing about seven-and-a-half feet tall in a corner of the living room. Made in 1860, it was found in North Carolina by her brother, an interior designer, who knew she wanted one because she had seen a nearly identical clock on a visit to the French farm her great-grandfather grew up on. In her own home, it serves as a reminder of her heritage and the family who came before.

After admiring the clock’s hand-painted flowers and intricate metal swan pendulum, Bill leads us downstairs to his favorite item: a birch-bark canoe, handmade by the Chippewa. It functioned as a water-worthy vessel on the Great Lakes until about 200 years ago, after which it spent time in a museum that later liquidated, sending it into the Hohulins’ possession in 1984. It’s one of the first things they hung in this room, which is why the books, tapestries, robes and countless glass wares are so neatly displayed around it, despite its lengthy frame. Bill has always been enthralled by the way the canoe was built, since its makers likely didn’t have access to metals to cut and form the wood.

After admiring the clock’s hand-painted flowers and intricate metal swan pendulum, Bill leads us downstairs to his favorite item: a birch-bark canoe, handmade by the Chippewa. It functioned as a water-worthy vessel on the Great Lakes until about 200 years ago, after which it spent time in a museum that later liquidated, sending it into the Hohulins’ possession in 1984. It’s one of the first things they hung in this room, which is why the books, tapestries, robes and countless glass wares are so neatly displayed around it, despite its lengthy frame. Bill has always been enthralled by the way the canoe was built, since its makers likely didn’t have access to metals to cut and form the wood.

The couple then leads me through a hallway decorated with glazed, hand-painted terracotta tiles from Mexico, and out a basement door to a landscaped pathway, along which stood a bronze sculpture called “The Indian.” The artist, Bill Jauquet, has been featured in museums and exhibits across the country; some of his patrons, Bill tells me, include Steven Spielberg, Emmylou Harris and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The Indian has a well-defined visage: “Bill Jauquet’s favorite face,” Bill notes. In front of him are dangling dream-catchers, and projecting from his head are decorative spikes, a sort of modern interpretation of a headdress. Though Jauquet never specified his inspiration, it reminds the couple of Black Hawk, which makes sense given the Wisconsin artist’s proximity to where the great Sauk leader lived and fought.

Caretakers with Intention

Back in her school’s teachers’ lounge, Lydia’s friends would sometimes notice her eating a meager lunch and guess that she and Bill must have bought another artifact. Indeed, upon stepping through their front door, one might wonder how two Midwestern schoolteachers could accumulate such an impressive display.

“We made sacrifices for the things we thought were worth it,” Lydia says—and it’s easy to see that they continue to bring her joy. She laughs and tells me that many guests ask how she dusts it all. “I get a kick out of dusting because it takes me to those times when we purchased it, and each one [is] a great memory.” Living amongst these curios—clearing them of dust, serving tea in them, telling time with them—is a simple reminder of how useful they’ve been to others, and now to the Hohulins.

This sort of intentional caretaking is a responsibility akin to the researching and accurate retelling of the objects’ history. Perhaps the necessity of preservative care is among the reasons collecting is generally done by public institutions today.

“Private ownership has led to a lot of abuse of artifact gathering and collecting,” Bill notes, as we discuss the issues some might take with the magnitude of their gatherings. “The typical mindset of museum curators is that private ownership abuses the ownership of artifacts because all the people can’t see it.” And the future of the Hohulins’ collection is not certain; while they hope it will continue to be valued and shared, they believe it has already fulfilled its purpose.

“Our gathering of artifacts was so that we could share them,” Bill says. “That was the intention, always,” Lydia adds.

Our Universal Past

Jill Rocke, a former student of Bill’s, remembers his passion for teaching history, recalling moments when he would use artifacts in class to bring lessons to life. “One day I walked in and he was sitting on this rug with no shoes on. I remember his feet, how his toes were formed. I can tell you where I sat… what the room looked like,” she explains, seemingly amazed at the vividness of her own memory. She believes the tangible nature of Bill’s teaching made her appreciate history in a way she hadn’t before.

Today, Jill teaches her own fifth-grade history class and recently asked Bill to borrow a few Native American artifacts to aid in a lesson. “It was unbelievable how many kids were in awe that [the artifacts] were from the Native Americans.” At the end of the school year, it was one of the things they remembered most. Jill thinks the artifacts led her students to more concretely grasp the idea that history is real: that it happened, and we are where we are today because of it.

Being surrounded by these items from the past—and truly understanding what they are and how they were used—allows for a collective appreciation of those who came before us, who paved the way in tools, trades and traditions. The Hohulins’ background as educators may help in the delivery of their storytelling, but anyone interested in collecting should realize the great responsibility that accompanies it. Intentionality is at the core, decorated by curiosity and respect.

Amid the challenging nature of collecting, the Hohulins’ thoughtful approach prompts us to stay curious about those who are different from us. In a world torn by cultural conflict, their curiosity cabinet urges us to search for similarities. It’s a warm, Midwestern reminder that the vast differences of the world can feel at home in your living room, and hopefully, your heart and mind. a&s