Local roast masters reveal the secrets to unlocking a bean’s true character.

He stoops over the machine, an artist of his own accord. Into the belly of this beast—a gas-powered, steel-drum Diedrich roaster at thirty-thirty Coffee’s downtown Peoria location—owner Ty Paluska pours 18 pounds of green, unprocessed coffee beans.

“It’s almost magic,” the roast master explains. “You have this raw bean that you’re essentially just cooking, and within 12 to 13½ minutes, it creates this amazing coffee that, depending on where it’s from, is going to taste different.”

Within that window of time—a parameter determined by Paluska and his thirty-thirty cohorts through trial and error, as well as preference—the bean’s chemical and physical properties will be transformed, converting it from unpalatable seed to luxury good. “It sounds simple,” he adds. “But then, between all that, you’re just trying to not ruin it.”

At thirty-thirty, Paluska strives to build a culture based on the philosophy that “good coffee, in its green, unroasted form, is perfect.” Their job, he maintains, is to preserve that perfection through the roasting and brewing processes—a task he describes as “exceedingly difficult in its simplicity.” Having garnered national acclaim and recently added a second location at Junction City, it’s a job thirty-thirty appears to be doing right.

Charting the Territory

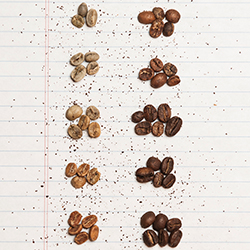

While most coffee today is roasted commercially and mass-produced, small-scale roasting is on the rise at specialty shops like thirty-thirty, who are dismissing the traditional, nondescript roasting “degrees”—such as French roast or city roast—in favor of profiles defined by flavor or tasting notes. It’s a cooking science, contingent not only on the bean’s origin and variety, but also on the “chef’s” senses—judging it by sight, smell, sound and taste to determine the perfect roast.

One minute, 30 seconds. Paluska points at the screen. “I love that—the rise,” he says, smiling as the temperature inside the drum, having stalled with the addition of room-temp beans, begins to climb again. He traces the graph mapped by Cropster Roast, a new piece of software he’s running on a trial basis, which conveys the roasting profile as temperature (y-axis) over time (x-axis). It takes the guesswork out of the process by tracing the beans’ RoR—rate of rise—over the duration of the roast, freeing Paluska’s hands to play with the machine, instead of scrambling to take handwritten notes on fluctuations in temperature, airflow and other variables.

Cropster allows for consistency in a trade that’s still relatively new, he explains. Paluska himself learned how to roast from a colleague, who learned it at a previous job—a trade learned by doing, passed on from one roaster to the next like a treasured recipe. “So much is still unknown about roasting coffee,” he adds. “It’s been done for [thousands of] years, but it’s still so new, and so unquestioned.”

Pure, Green Beans

In their pure, unroasted form, green coffee beans—actually the seeds of the coffee plant—are raw and inedible, but each variety embodies a unique flavor profile well before it hits the roaster. It’s the roasting that activates, via chemical reaction, the acids, proteins and sugars within the bean. And the variances in flavor can be stark, Paluska suggests. “The average person may not be able to explain the difference—like this has a tomato flavor, or this has more acid—but side by side, [anyone] could say, ‘This tastes different.’

“That’s why we put tasting notes on our bags,” he adds. “One crazy thing about roasting: there are thousands of potential flavors [with] the chemistry that’s happening inside the coffee bean… You have all these different acid chains that are changing while you’re roasting… Coffee has some of the most potential for different flavors as any other food out there.”

At thirty-thirty, Paluska tries to ask the questions that haven’t yet been asked, taking the art of roasting to a new level—one that reveals a bean’s true character. That requires “leaving the coffee oils within the bean to stretch the flavor,” or roasting just long enough to elevate the flavors to their tipping point—but not over. The desired results mandate close care under a watchful eye.

First Crack, Second Crack

Six minutes. The beans begin to pale, and Paluska pulls a few from the sample window. Nose to bean, he detects a nutty aroma, the beans having fully yellowed. But a popping sound, too, announces their progress. “When we get close to the 370° mark, you’ll start hearing that first crack,” he explains. “First crack” is the start of a light roast, the result of moisture within the bean having evaporated.

Eight minutes. The pops begin—a slow crackle that picks up quickly as the beans literally explode inside the chamber like popcorn. According to Paluska, beans should be roasted “light” only—between 12 and 13½ minutes, or between 406° and 410°F. (At 414°F, the shop’s espresso roast is the sole exception.) This range is lower than most coffee roasters, he acknowledges, but he believes it enhances the maximum flavor profile of each bean. Any hotter and he encroaches on “second crack”—the roasting stage characterized by a temperature of 440°F —when the bean pops audibly a second time and “those flavors, in the form of oils, are released.”

By second crack, you’re tasting carbon. “It’s like a ‘well-done’ taste,” Paluska notes. “We’re trying to highlight what’s there in the bean, but roasting it a little lighter, so you’re tasting the terroir [the unique combination of soil, climate and other environmental factors that influence its ultimate character]—a wine term. It’s pretty exciting,” he says with a grin.

But roasting so light requires using only the best beans, he adds. “If you’re getting high-quality beans, you’re going to be able to taste the full flavor. If you have a sub-par, commodity-grade coffee and you roast it light, it would taste bad, which is why a lot of places traditionally roast darker,” he explains. “When it’s a darker roast, you just taste what people are accustomed to tasting in coffee—that bitter, smoky sort of taste… A lot of people play on that. They can just get cheaper coffee and say, ‘This is what coffee tastes like.’”

But like every aspect of the culinary world, taste is subjective and prone to consumers’ roast-level preferences like flavor, time of day and fondness for caffeine (the darker the roast, the less caffeine). And just like brand loyalty, light and dark roasts yield devoted camps.

Life and Breath

Life and Breath

“Once the beans hit first crack, [they] are good to be ‘coffee,’” declares James Cross, owner of Leaves ‘N Beans Roasting Company. “You can pull them out and grind it and drink it, and it’s coffee. From that point on, the longer it’s in, the darker roast it gets.”

As he talks, his hands flit expertly around the shop’s artisan-choice roaster—an intimate choreography that’s second-nature after eight years in the business. To say Cross is enthusiastic about coffee is an understatement. In the Peoria Heights shop, where he singlehandedly roasts two or three times a week in a tiny room above his burgeoning wholesale and retail operation, his enthusiasm is quite literally fueled by the stuff. “You don’t even need to drink coffee to get the caffeine in your system—you just breathe it in back here!” he jokes. In all seriousness, a definite buzz hangs in the air.

Like Paluska, Cross lives and breathes coffee—a craftsman elevating the science of the roast to a serious art. That unreserved passion is evident in the variety and quality of his beans—an offering of more than 70 light and dark roasts, single origins and blends from around the world—appealing to a wide range of customer tastes. In the lighter roasts, Cross says, he’s bringing out “all of what the beans have to offer for taste,” while in the darker ones—he’s merely “taking flavor from the bean and adding flavor from the roaster.”

Everything at Leaves N’ Beans is roasted to order, requiring a 24- to 48-hour notice for wholesale orders so clients get “the freshest coffee possible.” Once roasted, he says, the coffee should be used within two weeks to maintain its “gourmet freshness.” Once it’s ground, time’s up. “You really don’t want to grind it until you’re going to brew it,” he explains. Paluska agrees. “After you grind it, its life expectancy is like 15 minutes,” he says flatly.

“Objectively Subjective”

Ten minutes, 30 seconds. Paluska stretches and grabs a lever, adding airflow to the beans. “We must make sure it doesn’t get too hot too quick.” Steam pours out from the top of the machine. “It’s starting to smell more like coffee,” he declares, turning on a fan to prepare the cooling tray, lost in thought.

“We try to be objectively subjective as much as possible,” he says. “There’s a difference between boxed wine and high-quality wine. Just because you like boxed wine doesn’t make you stupid, but there’s an understood quality that kind of goes along with that… Some people, that’s what they like—that’s what their palate likes. We get a bad rap sometimes, but we’re a craft industry, so we’re going to take a lot of pride in what we’re doing. And we know it tastes better because we’ve seen some of the best coffee in the world.”

Twelve minutes. Paluska turns, all attention to the beans. He jostles a few in the sample window, noting the change of color. Nose to bean: “We’re getting close.” The next 30 seconds, his laptop forgotten, the roasting becomes a sense-driven crescendo as Paluska puts the finishing touches on his beans—a flurry of sniffing, examining and listening until… CRASH!

Twelve minutes, 45 seconds. The lever released, a sea of evenly toasted, caramel-brown beans pour into the cooling tray. “414 degrees!” he announces, and with a click of his mouse, stops the graph in motion on screen. Here, they’ll rest for five to seven minutes until they hit room temperature, ready to bag.

The Perfect Cup

“We got an organic Peruvian in one time just to try,” Cross says. “Best coffee I’ve ever had in my life—the smoothest, cleanest coffee you could ever taste. I get made fun of for this, but when you drink it, the best way I can describe it is that it’s ‘fluffy.’ It almost inflates in your mouth,” he says dreamily. “When you drink it, it just fills your whole mouth and goes across your taste buds—a really, really good coffee. And because it’s so smooth and clean, it almost tastes like you’re just drinking the most purified water.”

That Peruvian bean is now a staple at Leaves N’ Beans, where Cross orders seven 150-pound bags of it at a time to satisfy his customer base. According to Cross, top quality is really all about freshness. “I don’t necessarily know what makes the perfect cup of coffee,” he admits. “My number-one goal is just to make sure it’s fresh.”

Twenty minutes. Paluska pops a couple of freshly roasted beans into his mouth from the cooling tray. The completed batch is a 50/50 blend of Costa Rican Tarrazu and Guatemala Waykan. Crunching, he points out the roast date and flavor profile stamped onto each of thirty-thirty’s individual bags of beans: “pear, mango, almond, chocolate, fruit punch.” The results of this meticulous process sell quickly—some 2,500 pounds per month—but for this roast master, it’s about far more than sheer numbers.

“[Craft roasting] is a very close-knit community, more so than a lot of other industries, which is sort of fun,” he notes. “This is not a job you do to make a great living—it’s a job you do because you love it.” And so, turning back to his craft, he pours another round of beans into the chamber, all senses ready for the next roast. a&s