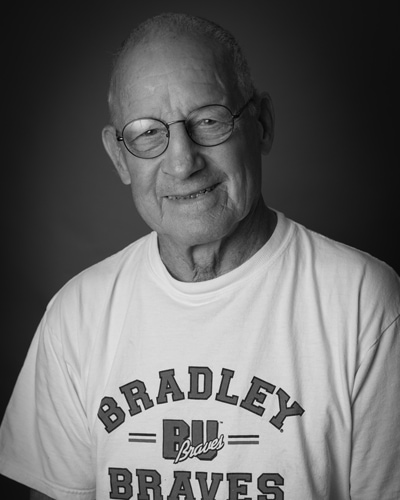

Photography by David Vernon

A full-sized tennis court sits on the 95-acre family farm in Norwood, Illinois, where Dr. Donald E. Rager and his wife, Laura, call home. Defying his 86 years, a weekly tennis match tops the list of current pastimes of the hesitantly retired doctor, who in fact, still works—interviewing candidates for medical school and delivering the occasional lecture. Spry to his core, Dr. Rager’s energy is contagious—it’s no surprise he’s touched so many lives through his passion for teaching and healing through medicine.

Born in Peoria, Rager graduated from Woodruff High School in 1950 and worked as a machinist apprentice at Caterpillar for three years before serving the U.S. Army in Korea from 1953 to 1955. He graduated from Bradley University with a bachelor’s degree in biology and chemistry in 1960, and from the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago two years later. Returning to his hometown, he opened a solo practice and worked in general internal medicine for two years before becoming chairman of the Department of Internal Medicine and residency program director at OSF Saint Francis Medical Center. He held that position until 1982, when he was named Director of Medical Affairs at OSF Saint Francis.

His first retirement lasted just five years. In 1999, he returned to the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria (UICOMP), where he had been a faculty member throughout his career, in order to serve as interim regional dean. He then served as regional dean for five years, playing key roles in establishing UICOMP’s Cancer Research Center and founding the Donald E. Rager, M.D., Clinical Skills Laboratory.

Dr. Rager has earned a string of honors in his lifetime, including the University of Illinois College of Medicine’s Clinical Instructor of the Year and Faculty Member of the Year awards; the Endowed Leadership in Cancer Research Award and Golden Apple Award for Teaching Excellence; Christ Church Limestone’s St. Barnabas Award; the Central Illinois Workforce Development Board Appreciation Award; and Easterseals’ Pillar of Distinction. He has served the community on a range of boards, including the Red Cross Central Illinois Chapter, Children’s Home Association of Illinois, Bradley University and Peoria NEXT. In their free time, the Ragers enjoy traveling and spending time with their three sons, 10 grandchildren and 23 great-grandchildren.

You are a Peorian through and through, born and raised here. Tell us about growing up.

I was born in 1932. At the time, my parents rented a home in the Averyville area. I walked to school, Kingman [Primary], just a few blocks away. I was not much of a student in those years (laughs). I remember what they called, “passing the grade on condition”… That happened for several years. But in eighth grade, I had a teacher that I really liked. She taught me about bird watching, and she and I developed a relationship, and I began to become a little more studious.

One of the more important assistants in my whole life’s development was my brother Chuck—he’s four years older than I am. He was the star athlete… and a scholar. I stumbled along, and the coaches all had expectations that I would be a good athlete. I was what I called the sixth man on the basketball team—I was never on the starting five, but always got in the game. That was good enough for me. Then I injured my knee my senior year of high school.

In the later part of my senior year, my father, who was a longtime employee at Caterpillar [as] the supervisor of inventory control, sat me down and said, “They’ve got a great apprentice program at Caterpillar and you ought to sign up for it.” So I signed up and became a machinist. I wasn’t thrilled with it, but I became mechanical and learned how to run all kinds of machines and factories.

You served two years in Korea—thank you for your service. What was that experience like?

I was anticipating that I was going to be drafted during the Korean conflict, so I signed up for the Navy Air Corps. They had a training program above Chicago [Naval Station Great Lakes]. They accepted me, and we had all these goodbye events with family. But I had a physical exam in Chicago, and they said, “That left knee is too unstable; we can’t take you,” so they sent me back home (laughs). But then a few months later, the Army said, “We don’t care about that knee.” So I got drafted in the Army.

I was sent to infantry school in Fort Riley, Kansas. About halfway through my training, I ran into a friend from Woodruff—an athlete from Peoria. He said, “You don’t want to go to Korea as an infantryman.” So he put me in truck mechanic school. I shipped over to Korea in 1952. I was in Pusan, as far away from the shooting as you could get.

We had an inspection of our motor pool and we flunked it, so the company commander fired the motor sergeant who had been in the Army for 20 years. I didn’t even have one stripe, but he promoted me to motor sergeant (laughs), so I took over the motor pool. Then we had a big fire that burned down our whole ramshackle company, so they requisitioned two Caterpillar bulldozers to build a new company on another little hill overlooking the Yellow Sea.

When the first dozer came over, one of the men there, who… was a heavy equipment operator in his civilian life, said, “We have another one coming, and I’ll teach you how to run it.” I was the closest to being another qualified person because I worked at Caterpillar, so… I finished out my career in the Army as a Caterpillar operator.

When the first dozer came over, one of the men there, who… was a heavy equipment operator in his civilian life, said, “We have another one coming, and I’ll teach you how to run it.” I was the closest to being another qualified person because I worked at Caterpillar, so… I finished out my career in the Army as a Caterpillar operator.

But… right next to our company in Puson was a Maryknoll Sisters Hospital for both the military and civilians. I volunteered there in the evenings and enjoyed the work. I thought, this is kind of fun—maybe I’d like to do this in the future.

What was it about that hospital that sparked your interest in medicine?

I’ve always thought that you shouldn’t go through this life without leaving a mark, and I wasn’t going to leave a mark as a machinist, although I still do machine work. I wasn’t going to make a mark as a bulldozer operator, although I still drive tractors around the farm. I thought medicine was the place to go.

…But it didn’t happen that way. I got discharged and Cat contacted me and said, “Do you want to complete your training in machine work?” And I said no. They said, “Why don’t you go into engineering? We’ll give you a scholarship.” So I went to Bradley for mechanical engineering. I took one year and I said, “I don’t dig this.” But I was getting straight As. I learned that if I worked hard and was studious, I could conquer [anything]. So I changed to pre-med.

Tell us about meeting your wife and raising your family while attending medical school.

We happened to end up in the same class, English Master Works, at Bradley—so that sparked the flame. About a year later, we got married—in 1956, in the fall—and we had our first son, Brad. And then in ‘58 I was accepted into medical school, so we moved to Chicago. So we lived there, I went to medical school, and the rest is history. We had two more kids—Brian, and then two years later, Bruce.

Why did you decide to leave Chicago after your residency and come back to Peoria?

These days, I still interview candidates for medical school and the university. When I interview them, I ask questions like, “How many medical schools are you applying to?” “Twenty.” “How many are you interviewing at?” “Twelve.” That’s the way it works—there are so many more individuals applying for schools than can possibly get accepted. But I applied to [just] one, because I couldn’t afford to go anywhere else: the University of Illinois. I got accepted, but that’s absolutely unheard of—no one in their right mind would do that these days.

We then decided to also take our four years of residency training in Chicago [at the University of Illinois Hospital]. At the end, the chairman of the program asked me to stay and take a fellowship in infectious disease, but I said, “No, I’m going back home and I’m going to practice medicine.”

So you knew all along you wanted to return to Peoria?

Yep. He said, “So you’re going back to the end of the railroad tracks?” And I said, “I sure am!” (laughing) So I did. I set up a practice of general internal medicine as a solo physician… but at the same time I stayed connected to the University of Illinois Hospital. I used to go up to Chicago once a week and train medical students. I spent one day every week along with Bill Albers [pediatric cardiologist] and Ralph Bransky [thoracic surgeon] for two or three years.

That’s devotion!

Well, I like teaching (smiling). When I got established with my practice in Peoria, I applied to all three hospitals and was on staff at all three… At that time, the only residency program in Peoria was at Saint Francis in internal medicine. They decided they wanted to update their residency education and set out to hire a full-time chairman, which they’d never had before. So I was the first full-time chairman of the Department of Internal Medicine and the residency program director at Saint Francis.

When I got there, Ken Furlong had left and went to Methodist, so I inherited the coronary care unit. I became a cardiologist—I didn’t have any choice (laughs)… until a couple years later I could recruit [and] hand it over. Then I spent some time in the original dialysis unit… and I became director of that unit for a year… My life in internal medicine was all about that—I was a specialist in about four different things. I even did all the liver biopsies at the hospital for a couple of years, for lack of anybody else who could do it!

But I guess one of the important things I learned about learning on the job is that there had to be a better way. Learning on the job is risky business for all those poor patients out there… We finally established the [Donald E. Rager, MD, Clinical Skills Laboratory] in order to develop methodology that would be more appropriate to learning these things.

Tell us about the College of Medicine campus in Peoria and the thinking behind its inception.

There was something called the Campbell Report—a state-commissioned report on medical schools in Illinois. Amongst the things he found was that there were five medical schools at the time—all in Chicago—and only 30 percent of the physicians that would graduate from those schools ended up in Illinois. The state was appalled at that. So, they set out to develop a methodology that would keep physicians in the state of Illinois.

They learned that where the trainees took their final years of residency training was most likely where they would settle in for practice. So they decided to disperse medical education and get it all out of Chicago. That spawned the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine and the expansion of the University of Illinois College of Medicine to the sites of Peoria, Rockford and Champaign-Urbana. So I got knee-deep in that and became a part of the original medical school development… and eventually we ended up with a medical school [in Peoria]. We have to thank a lot of locals for that. Dick Carver was the most important—he was the [Peoria] mayor at the time.

Tell us about retiring, and then “un-retiring.” Did you get bored?

(Laughs) While I was the medical director at Saint Francis, I decided it was time to retire. I was 62, and that was in 1995. So I retired—had a big party and got all these awards and dispersed all my patients in various directions. I was happily working on my tractor down in the barn, and I kept teaching at the medical school, gave a few lectures here and there.

So a call came in from the medical school [his name had come up as a potential candidate for the deanship]. My wife and I didn’t think they’d choose me. So I said, “Okay, put my name in the hat and we’ll see what comes of it.” Well, in December 1999 after a few meetings, I became the interim dean. They said they were initiating a nationwide search for a dean, and it’d probably be a year and a half, or two. The next thing you know, it’s five-and-a-half years later! And I said, “Okay, now I really have to retire.” (laughs)

As it turns out, those were fun years in many ways because… I no longer had patients to see or night calls, and it was an organization of professionals—physicians, PhDs, nurses and civil service employees—who were incredibly good with people. So I learned more about teamwork in those years and took classes in management.

Let’s talk about Peoria NEXT. How did that collaboration come about?

At the time I was hired as dean, I had meetings with all the big shots in Chicago and we talked over what they considered were the issues in Peoria that needed to be dealt with going into the future. At the top of the list was that research was anemic in Peoria. I took that seriously and set out to get information about research capabilities and what it took to build a research program.

I got the word out that we were seeking some key researchers, and along came Dr. Rao, cancer researcher from the Neuroscience Department at the [University of Texas’] Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. He was looking to make a move so we made a pitch… and we ended up recruiting him. It was really upstream, and we didn’t think it would happen, but magical things do happen… He wanted to branch out and start researching breast cancer, melanomas and other cancers, and needed five key researchers to head up all these divisions. He had a huge vision of what the future might bring.

Dr. Rao is since gone… but this research effort didn’t end with him. I said, “How else are we going to recruit and generate research activity in Peoria that’s more robust? So I got talking with the community advisory group [at UICOMP] and… [former Caterpillar CEO] Glen Barton, and I had a lot of conversations with others. And we said, “Let’s create a Peoria research facility, a collaboration, a ‘research university without walls.’” So we set out to do that, and that became the Peoria NEXT initiative. Bradley and ICC joined and Caterpillar pitched in, and we slowly grew.

The design was to simulate and move research from the laboratory into practical life. That’s what the Peoria NEXT Innovation Center was all about and that’s been really quite successful here. The building [801 W. Main Street in Peoria] got built and many organizations got products developed there, but as time went on, we began to scale down and decided to go down the pathway of research support that didn’t involve medical research. I was on the board of Peoria NEXT from 2002 until we just closed our doors this past December 2017. It doesn’t exist anymore as a separate not-for-profit, but Bradley took over the building and the whole enterprise. As it turned out, we ended up giving the Community Foundation [a large gift] to use on scholarships at Quest [Charter Academy] for students’ futures in science and education.

How else have you stayed busy in your retirement, the second time around?

Because I don’t like to let any grass grow under my feet, we decided the Clinical Skills Lab needed to expand. We have first-year medical students here [in Peoria] now. Up until the previous year, students had their first year at Chicago or Urbana, but… this is an expansion of a class size of 104 students or so, and we need more space. So I’m now heading up fundraising activity to expand the facilities.

Meanwhile, I’m involved at [Christ Church Limestone] and raising funds to rebuild the [bell] tower. We’ve managed to put together enough money to get that started… This is my latest passion. The church was built in 1845 and is still standing. We’re doing repairs on it now. It’s made of local limestone—all laid by hand—and the inside is local walnut. Meanwhile, I took on the job of chairman of the graveyard committee.

What does that involve?!

It involves learning about graves and graveyards, and that’s a lot of fun. The first burial was in 1834, before the church was built. There are a lot of old graves, but we also buried two people there last year. It’s an active graveyard, but the stones have not been taken care of. So I went to a gravestone repair workshop in Ohio [with Laura] in June.

In terms of legacy, what do you want to be remembered for?

Coming up as a common man who saw opportunities and grasped them, and leaving behind a better world. That’s all anybody wants to do, I think: to leave behind a better world. If I did my part in that, then I did my part. In spite of the sacrifices, medicine must have been a rewarding career.

I wouldn’t do anything differently. I say that to all those I interview to become medical students: if you’re up for it, there’s nothing more rewarding in life. You’ll gain friends, and you’ll go to your grave being happy that you left something behind.

Anything else you’d like to add?

In the end, we also have to have faith in a higher power, and to look for guidance day by day. You go through life in a prayerful manner and hope for the best. iBi