From the streets of London to Peoria’s Warehouse District, Colt Sandberg is always pushing, ever moving.

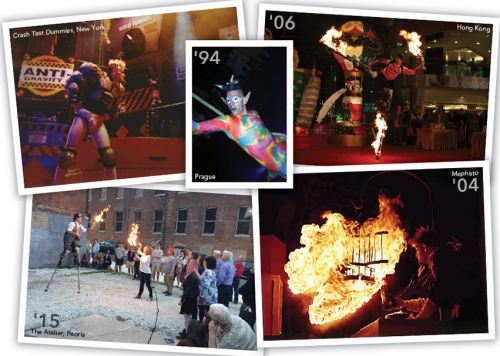

It’s First Friday, and a man on stilts is struggling to escape from a fastened straitjacket outside The Atelier, an art studio in Peoria. A variety of facial expressions are painted across the crowd—amusement and confusion, skepticism and awe—as all await the fate of the man whose head rises more than 10 feet above hard pavement. Some snap pictures on their cellphones, others back away, and several cheer. An otherwise typical gallery visit has become a crash course in street performance by “Cosmic” Colt Sandberg.

In a photoshopped world of computer-generated imagery, it’s not often one sees old-school, Buster Keaton-style stunt work—but traditional street performance challenges its audience in a way CGI does not. It’s no hoax: the dangers of broken bones, busted knees and dislocated shoulders are quite real… and so is the vulnerability shared by performer and audience. Today, as Colt Sandberg “sculpts” his largest piece of art to date—a building in Peoria’s Warehouse District—he hopes to harness that sense of creative intimacy.

A Showman’s DNA

Colt Sandberg spent his childhood growing up in Princeton, Illinois after his parents’ divorce. From time to time, he would visit his father, architect and former Peoria Councilman Gary Sandberg, and these moments had a significant impact on him—including the initial spark for the “life-or-death edge” that saturates his life and art. “My dad was a racecar driver,” he explains. “I grew up with the smell of gasoline… playing with engine bits.” A true iconoclast and Peoria icon, his father also fed Colt’s love of architecture—and his desire to push boundaries. “We’ve got it in our DNA to create and to push.”

After spending time in Chicago and Los Angeles, Colt moved to London in 1992 at the age of 21, working as a chef in a local pub. One evening, he was hitchhiking back to the city when a musician from the south of London picked him up. By the end of the ride, they were not only friends, but roommates. Before long, he struck up a friendship with their neighbor, an art dealer and rigging technician at the Piccadilly Theatre, who traveled abroad twice a year to bring artwork back to London. One day, he asked if Colt was interested in taking over his work at the Piccadilly while he was away. He accepted the challenge, and soon, Colt was walking through the stage doors as a rigger. For the next three months, he lived and worked as someone else. “No one questioned it.”

After spending time in Chicago and Los Angeles, Colt moved to London in 1992 at the age of 21, working as a chef in a local pub. One evening, he was hitchhiking back to the city when a musician from the south of London picked him up. By the end of the ride, they were not only friends, but roommates. Before long, he struck up a friendship with their neighbor, an art dealer and rigging technician at the Piccadilly Theatre, who traveled abroad twice a year to bring artwork back to London. One day, he asked if Colt was interested in taking over his work at the Piccadilly while he was away. He accepted the challenge, and soon, Colt was walking through the stage doors as a rigger. For the next three months, he lived and worked as someone else. “No one questioned it.”

At the Piccadilly, he would hand-crank furniture onto the stage and rig artists up in gear to fly them high above the audience—his first taste of live performance. In between cues, most of the crew would head to the pub. “After the first couple of weeks, I got sick of the pint thing,” Colt says. “I noticed that next to the dressing room was an old set of juggling fire torches from the ‘70s. For the next two months, I taught myself how to juggle during my breaks.”

Soon he was working the festival circuit, including the legendary Glastonbury Festival, where he performed for much of the ’90s. Between festivals, he would travel the continent with friends, trying to make ends meet as a street performer—and on Christmas Eve of 1993, he found himself in Spain. He describes himself as a “terrible juggler” at that point.

“I didn’t even have juggling balls… I was just using oranges. We were that destitute,” he recalls. “You can only drop an orange so many times before it’s nothing but a mess.”

Running out of oranges, he asked a boy from the crowd to get more from the store. When the boy tossed one up to him, it hit Colt in the head, and the audience laughed. “And then one of those light bulbs happened,” he recalls. “I realized I didn’t have to be… the perfect juggler—I just had to be funny and interactive.”

He spent the rest of his time in that city having local children throw oranges at his head—“playing the village idiot”—much to their delight.

Rooted In Movement

As Colt’s skill and confidence grew, people began to take notice. Arriving in Athens, he was immediately booked on a TV show. He learned to walk on stilts, then he was juggling on top of them—which wasn’t easy on his body. “They’re uncomfortable,” he describes. “You bleed and you bruise and it hurts… a lot. You have to have a tolerance for pain, or you learn it.” When he added fire to his repertoire, the crowds continued to swell. “It was dangerous,” he notes with a smile.

Traveling across Europe, Colt began to meet other like-minded artists, including an eight-person circus from Switzerland. This led to his first group collaboration, a self-described mixture of the performing arts, fire, clowning and music. Utilizing a 1940s-era military crane for aerial acrobatics and trapeze, Kran (English: “crane”) was a completely different kind of production, an open-air, absurdist circus complete with Shakespearean, good-vs-evil storylines. No longer just a solo performer, Colt was now part of a larger narrative.

“I could use my skills, have a character and develop a dialogue with the audience,” he explains. “It wasn’t just doing a trick for the sake of a trick.” He built props and learned to juggle flaming toilet plungers—while throwing knives. He even learned to play the saxophone for one act. “We were not about doing ‘technical’ circus. It was really all contemporary, absurd and fun.”

Following this initial circus experience, Colt continued to hone his skills as he toured around Europe. “I was booking myself in London, Prague and Athens every weekend,” he says. “I didn’t even take my makeup off.” After six years of constant travel, late-night parties and street shows, he was ready for something new.

Riding the momentum of his success in Europe, Colt hit New York City in 2001, where he landed a role in a Broadway production called AntiGravity’s Crash Test Dummies. Produced by the up-and-coming performance troupe AntiGravity Inc., “it was a theatrical storyline about the dummies who test cars,” he explains. “But we were the dummies in the basement who test household goods, trying to become the dummies who test cars.”

Crash Test Dummies was a hit—the New York Times called it a “slam-bang show.” “We really turned New York on its head,” Colt recalls. Soon, the AntiGravity team was offered a contract for a project in the Bahamas—but their trajectory literally changed mid-flight. Having boarded a plane in New York on September 11, 2001, they were grounded in Miami for days as flight authorities scrambled in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks. Amidst this air of uncertainty, the investors bailed—and “that project just disappeared.”

But Colt never stops moving. His next collaboration, another AntiGravity production, was a personal tribute to New York, a benefit performance in the wake of 9/11. In the years that followed, he was a key technician on the design and construction of Dragone Macau, a large aquatic theater in China; a pyrotechnician and stunt performer with the DareDevil Opera Company; and a senior technician with Cirque du Soleil, the world’s largest theatrical producer. He was never without a project: from assisting with tsunami recovery efforts in Thailand, to transporting sailboats around the world, to his continuing work with Cirque du Soleil in the show Kooza. Ever nomadic, Colt was not rooted in any particular location, but in himself. “I’m open to being uncomfortable,” he adds.

But Colt never stops moving. His next collaboration, another AntiGravity production, was a personal tribute to New York, a benefit performance in the wake of 9/11. In the years that followed, he was a key technician on the design and construction of Dragone Macau, a large aquatic theater in China; a pyrotechnician and stunt performer with the DareDevil Opera Company; and a senior technician with Cirque du Soleil, the world’s largest theatrical producer. He was never without a project: from assisting with tsunami recovery efforts in Thailand, to transporting sailboats around the world, to his continuing work with Cirque du Soleil in the show Kooza. Ever nomadic, Colt was not rooted in any particular location, but in himself. “I’m open to being uncomfortable,” he adds.

A Sculpture in Brick

“And now, here I am with this huge technical challenge—and at the same time… an artistic endeavor. It’s personal.” Colt Sandberg is referring to his latest project: a 19th-century building in Peoria’s Warehouse District which he has dubbed “Advance Space.”

Originally home to a cigar factory, then a manufacturer of window blinds, its renovation was intended to be a joint endeavor with his father. After his dad’s untimely death in 2013, Colt chose to continue the project, hoping to turn the building into a creative space. He calls it “his biggest sculpture to date”—a picturesque, yet practical piece of three-dimensional art that belies his roaming spirit.

“This is the first project I’ve taken on that has a permanent-like quality,” he affirms, spying a new artistic medium in these old bricks. In the Warehouse District, he sees the bigger picture, and hopes to bolster the community and spirit that are essential for the arts to flourish here. With his theatrical background and incredible technical skills, he could provide a “Cirque-quality” level of production to a variety of artists and performers. And with River City Labs, Peoria’s “makerspace,” having recently moved into its second floor, the building is already a creative force.

“What’s important to me is that people really start coming together,” Colt says. “I want everyone to ‘advance their space’ when they walk in that door—whether it’s the bricklayer, a guy making a drone, or a girl painting. And maybe one day, I’ll put a little cabaret in the back corner…” he muses, “turn it into an old speakeasy.”

And this is where we find “Cosmic” Colt Sandberg today: sculpting a space for others to create, to dream and to experience novelty. It’s the fulfillment of a personal passion—the union of his life and work. “I’m not producing a street show… but my formula hasn’t changed,” he declares. “I always like to take people through a bit of a journey with me.” a&s

To learn more about Advance Space, visit facebook.com/advancethespace or email Colt Sandberg at [email protected].