Through a lifetime of chasing dreams, Judy Page has given it her all… and has no regrets.

Once you’ve heard her voice, you will never forget it. Bursting forth is a deep, vocal caress that channels the cries, pain and longing of love lost; the whispers of stories scandalous and vexing; and the unscripted silences that allow you to sit back and just… take it all in.

Singing background vocals with Ike and Tina Turner, meeting up with an old acquaintance by the name of Richard Pryor, and honing her unique style with a popular central Illinois band in the 1970s—these are the stories that color and shape her performances. She may not recount them, but you can see it in her eyes and hear it in her voice and infectious laughter.

Judy Page-Adkisson Stokes’ life is a song itself. And like any good jazz number, you’re never quite sure where it’s heading next.

Learning to Sing

Judy grew up near Bradley Park in Peoria, not far from Corn Stock Theatre. In her earliest years, she remembers learning songs and harmonies from her mother. “I was three when I learned my first song—and of course it was a spiritual,” she recalls. At family gatherings, relatives would pay her a nickel or a dime and beckon: “Sing this song for me!”

Her voice was explosive, drowning out those around her. “Judy, start us off!” her schoolteacher would say with a knowing grin, as she led her classmates through every word of “The Star Spangled Banner.”

When school was over, she would come home and head straight to the basement. This was her domain: a large mirror leaning against a wall and a hairbrush that made for a makeshift microphone. “I’d sing in the mirror and see how I looked,” Judy explains. “Nobody upstairs paid any attention.” Her entire family could sing, so she felt encouraged to grow that talent. “But they didn’t have that desire to want to be on stage, I guess. It’s not that I wanted to be a star… that never even occurred to me. I just wanted to sing.”

Even before her teen years, Judy performed in talent shows at the Carver Center in Peoria. At 15, she landed her first professional gig with an eight-piece R&B band. Meanwhile, her high school choir director helped her tone down her voice and learn how to blend in with a group: “She taught me how to sing with a person next to you.”

A young Judy Stokes onstage at a Carver Center talent show, 1957, with her sister Jonelle Stokes Johnson and Eddie Mae Washington

Around this time, Judy started sneaking out to catch live music at places like Collins Corner, a rowdy and legendary club that featured a mix of jazz and R&B bands. Though she rarely got further than the parking lot, she’d stand outside and listen. For her, the music was as fascinating as it was addictive.

On the Road

Soon Judy was going to shows at Baty’s Barn, a musical venue on Galena Road in Peoria that was hosting up-and-coming soul and R&B acts. She first saw Ike and Tina Turner perform there in 1962. A year later when the powerhouse duo returned, Judy was back in the audience. “Ike Turner gets on the microphone and goes, ‘I’m looking for anybody out there who knows how to sing… I’ve got to replace an Ikette!’” Though Judy’s friends encouraged her to go up to the stage, she shyly refused. But someone decided to pass her phone number along to Ike Turner.

“The next day I get a call from the Jefferson Hotel—and it was Ike Turner,” she explains, the astonishment still present in her voice decades later. “Somebody told me you know how to sing,” came the voice on the phone. He asked her to come to the hotel for an audition.

Thinking back, Judy laughs at a memory almost too absurd to be true: rushing from the kitchen to her father, breathlessly asking for permission to head to the Jefferson Hotel in downtown Peoria to audition for the Ike Turner. “You’re not going out to a ho-tel to audition for somebody!” he responded. Crestfallen, she shuffled back to the phone. “My dad says I can’t come down there.”

Instead, a determined Ike Turner found his way to her family’s front door. “I stood in that living room—I mean, talk about scared!” Judy laughs. Mustering up the courage, she sang Etta James’ “At Last”—and she did it acapella. “How would you like a job being an Ikette?” Turner asked.

“Oh my God!” Judy recalls exclaiming. “I have graduation coming up in two weeks!” Turner needed someone immediately, but he promised to call her after she graduated. “I thought I blew it,” Judy says. “But two weeks passed, graduation happened, and I believe it was the next day that the phone rang.”

“This is Ike Turner. You ready to come on the road?” Judy’s mother, not yet ready to send her 17-year-old daughter off alone, accompanied her on her first-ever plane trip. When they arrived in Atlanta, Judy was quickly ushered into a rehearsal. “The girls were there and they’re trying to show me what to do on stage,” she recalls. Each of the Ikettes performed their own special song, and Ike had decided that Judy would sing “At Last.” Asking when she would first sing it, Ike’s response caught her by surprise: “Tonight.”

After her initial performance as an Ikette, Judy had no voice left. “I couldn’t even talk, I was so hoarse,” she recalls. That intensity continued, night after night. When she complained, Ike told her to sing through it. She was dressed up in shimmery, glitzy dresses (“with the fringe and all that stuff”), a wig and spiked heels, and at Tina’s insistence, absolutely no runs in the stockings. “I remember the first couple of nights on stage. I didn’t know the routines, and I was running into them!” she laughs. “It was an experience… And one that I’ll never forget.”

After her initial performance as an Ikette, Judy had no voice left. “I couldn’t even talk, I was so hoarse,” she recalls. That intensity continued, night after night. When she complained, Ike told her to sing through it. She was dressed up in shimmery, glitzy dresses (“with the fringe and all that stuff”), a wig and spiked heels, and at Tina’s insistence, absolutely no runs in the stockings. “I remember the first couple of nights on stage. I didn’t know the routines, and I was running into them!” she laughs. “It was an experience… And one that I’ll never forget.”

After a few days, Ike Turner managed to convince Judy’s mother that she could return to Peoria. In hindsight, his insistence that Judy would be safe (“I’ll take care of her!”) feels a bit foreboding. Tina Turner, Judy notes, was “just a sweet as she could be,” and Judy learned to stick to her like glue—as Ike became a growing threat. “He was pursuing me so much that I was scared to death. On the bus he’d make jokes: ‘We got a fresh piece of meat here! Who’s going to get her first?’ I’d be sliding down in my seat… and Tina would say, ‘Leave her alone, Ike!’”

Asked if she was ever starstruck by Ike’s advances, Judy smirks, responding with an emphatic no. “I knew what kind of reputation he had,” she says, shaking her head. “He would have [Tina] out behind the building, beating her. She would put makeup on and get back on stage like nothing had happened… He made it very clear what he was after. I was genuinely afraid.”

Meanwhile, touring took the group through the “Chitlin Circuit,” a performance route where African Americans could perform in racially segregated areas. As Judy ventured across the South, she encountered painful and violent displays of hatred. “It was the first time I had ever seen signs that said ‘Colored’ and ‘White.’ I was like, ‘Wow, they really do that stuff? You really have to go into a different door?’”

After six months on the road and increasingly scary encounters with Ike Turner, Judy finally called her mother and asked for a plane ticket back home.

Cross-Country Meeting

When Judy returned to Peoria, she knew she had to find a job, especially given her parents’ insistence that she would never make a living as a musician. Working for the school district, the telephone company, and eventually Caterpillar, a pattern soon emerged. Judy would get a job, save up money, quit, go on tour, call her parents for help, return home—and then the irresistible lure of music would take her back on the road.

“In the interim I managed to get in 25 years at Caterpillar. Amazing. How’d I do that?” she laughs. “I knew that if I left Caterpillar and came back within three years, I would not lose my seniority.”

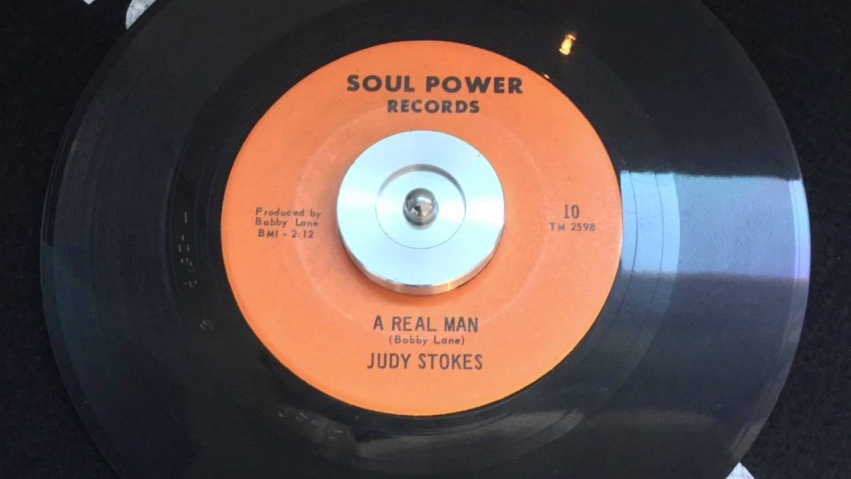

Although Judy downplays it today, her 1967 single is actually a rare and sought-after collectible, selling for hundreds of dollars online.

In 1967, Judy recorded and released her one and only 45rpm record in Rock Island, Illinois. “It was horrible,” she says, recalling the experience. Although she downplays the record today, it is actually a rare and sought-after collectible, selling for hundreds of dollars online. Thinking back to the B side of the single, entitled “A Real Man,” Judy purses her lips and sings mockingly: “‘My man! Makes me feel real now ya’ll…’—that stupid song is what I had to sing over and over again.” As a woman—and especially as a woman of color—she says that singing songs that were overtly sexist was expected of her.

The following year, Judy had an opportunity to move in with a cousin who lived in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. It was 1968, and the city was a cultural hub of the United States. She found a job at United Airlines and began to explore her new surroundings, always keeping her eyes open for opportunities to catch live music. One night, as she was heading home from work, she noticed a familiar name on a marquee: Richard Pryor.

“Did I mention the Carver Center? That’s where I first knew Richard from,” Judy explains. Growing up, she frequented the community center, where Pryor got his start emceeing events at the encouragement of Juliette Whittaker, head of Carver’s theater program. “We’d always ask Miss Whittaker, ‘Do you have to get him? He acts so stupid all the time!’ You had to wait for him and he’d drag everything out. We wanted to do the music!” Pausing, she sighs and shakes her head in mock disgust. “He was just so stupid!”

But when Judy saw Richard’s name in San Francisco, she knew she had to see him again. “Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles were opening for him… so I called him on the phone,” she says. He told her he’d leave two tickets for her at the door. When she and a friend showed up, they were ushered into his dressing room. “He’s got a couch, a chair and a coffee table with every kind of drug you can imagine,” Judy recalls. When she asked if he remembered her from their youth, he responded, ”Yeah, yeah, yeah! I remember you… you were ugly,” he joked, “but you could sing your ass off!”

But when Judy saw Richard’s name in San Francisco, she knew she had to see him again. “Patti LaBelle and the Bluebelles were opening for him… so I called him on the phone,” she says. He told her he’d leave two tickets for her at the door. When she and a friend showed up, they were ushered into his dressing room. “He’s got a couch, a chair and a coffee table with every kind of drug you can imagine,” Judy recalls. When she asked if he remembered her from their youth, he responded, ”Yeah, yeah, yeah! I remember you… you were ugly,” he joked, “but you could sing your ass off!”

The legendary comedian was on fire that night, and Judy recognized all the references he made to their hometown. “He was talking about Peoria and different people that I knew. My friend and I spent most of our time… rolling on the floor, laughing,” she says, her eyes lighting up at the memory.

While Richard would soon become one of the most famous entertainers in the world, Judy was still trying to find a direction forward. When friends encouraged her to enter a local talent contest, she agreed. “I didn’t win that night, but I was first runner-up,” she notes. When she returned the following week, she won—and continued to win for six weeks straight.

But, as she considered a job offer with the club’s 13-piece band, Judy heard her mother’s voice: You can’t do that for a living. “I opted not to take that chance,” she explains. It was time to return to Peoria.

Full Circle in Peoria

Back in her hometown, Judy returned to Caterpillar—and kept right on singing. Soon she was on the road again with a popular Midwestern band, the Marvin Sims Review, with whom she had toured briefly before her move to San Francisco. “That’s when my mom was really having a fit,” she laughs, recounting situations when her mother had to bail them out, sending money to buy food or gas. She also began singing under the name “Judy Blue,” forgoing her father’s surname, Stokes. Today, she sings under her mother’s maiden name as Judy Page.

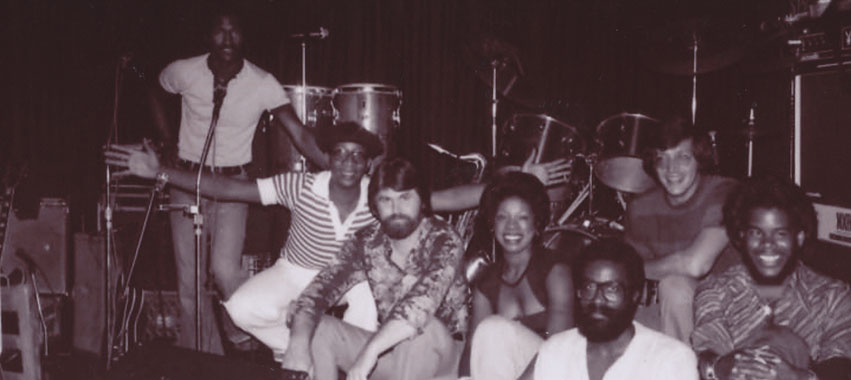

In the late seventies, Judy joined Kriss/Kross, a newly formed band featuring some of Peoria’s top musical talent: Preston Jackson, Steve Degenford, Gary Adkisson (Judy’s deceased ex-husband), Bryan Moore and Dave Parkinson. “We did contemporary jazz… people didn’t know that’s what they were listening to,” she explains. “But it’s different because they were throwing in up-tempo jazz. They were a little R&B, a lot of blues—and so I’d mix it up.”

Kriss/Kross members Preston Jackson, Alvin Butler, Dave Parkinson, Judy Page, Keith Boswell, Steve Degenford and Gary Adkisson, ca 1979-80

Over time, Judy says she began to sing jazz almost exclusively, returning to her first love. “This is the music that I’d be singing downstairs in that basement,” she says, recalling her childhood. “I still have most of the albums—Sarah Vaughan, Nat [King] Cole—that’s what I was using to sing down there.” Her life had come full circle.

In 2001, Judy had the opportunity to open for the great Ray Charles at the Peoria Civic Center, performing with Preston Jackson & Friends at the Tri-County Urban League’s annual Black & White Gala. Several years later she formed the band Speakeasy, which featured most of the members of Kriss/Kross, and today she lends her vocals to Judy Page & Friends—a rotating but familiar cast of characters, including guitarist Steve Degenford, who has been at her side for decades.

As Judy’s voice has deepened over the years, so has the raw intensity of her singing. “I don’t holler over the whole band,” she notes. She prefers intimate rooms and alert audiences: seated on a stool, dressed beautifully and singing the songs that move her—and everyone around her. “I love good lyrics—I’ll do a song just because I like what it’s saying. The music’s always pretty that goes with it anyway—but boy, the stories that the lyrics tell…” The stories from her own life are as plentiful as the thousands of songs she has memorized—and she somehow manages to convey it all in the poetry that is her voice.

A Healing Force

A Healing Force

Surprisingly, although Judy has been performing for decades, she has always struggled to feel at ease on stage. As a child, her mother suggested that she find a spot above the audience and stare at it, hoping it would ease her nerves. Laughing, Judy says that her mother’s advice stuck. “I sing to myself—I don’t look people in the eye,” she admits. “I guess I’m just in that zone and I’m concentrating on vocalizing.

“It takes a mental toll on you,” she adds. “I tell myself to open my eyes every now and then. Let them know you’re okay, Judy!” she laughs.

Because she sings from the joys and heartaches she has experienced throughout life, her performances are intrinsically emotional. “I’ve bottled that emotion up and I let it go.” In this regard, music has been a healing force for Judy. “That music is my man, my love. It won’t hurt me—it won’t break my heart,” she says. “Music just makes me happy.”

Asked what she hopes her audience takes home with them at the end of the night, Judy hopes they hear their own life’s story in the music. One of her favorites, she adds, is Shirley Horn’s “Here’s To Life”—a modern-day jazz standard. Closing her eyes, she begins to sing softly: “No complaints and no regrets / I still believe in chasing dreams and placing bets / But I have learned that all you give is all you get / So give it all you got.” a&s