A distinctive collection of artwork will open at Lakeview Museum on October 1st and continue through January 15, 2012.

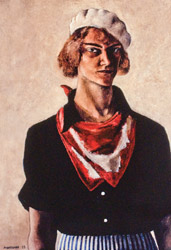

Isn’t she lovely? Her name is Bessie Potter Vonnoh, and she was 35 in 1907 when her husband painted this vision of her with one of her statuettes. She was a remarkable sculptor, a pioneer woman artist. By the time she was 22, she had her own studio in Chicago at the Athenaeum Building, on the same floor as popular sculptor Lorado Taft, known for his large-scale works and his book, The History of American Sculpture, published in 1903.

Bessie Vonnoh and a number of other accomplished women artists, well known in their day, left a legacy worth noting. They made a difference in American art, enriching the cultural experiences of their Illinois communities. It is their work you will see and their stories you will learn at Lakeview Museum’s fall exhibition, Skirting Convention: Illinois Women Artists 1840 to 1940.

What Women Do

Seventy paintings, drawings, sculpture, prints and photographs, gathered from around the state, will be on display. These artists had plenty of restrictions and unique challenges to overcome, but they did what women always do, regardless of their circumstances: they worked hard and produced art, no matter what.

The problem is we don’t know much about them. They weren’t included in writings that would have kept their memories alive for the future. When you come to the exhibit, you will see the work of 64 women artists and learn about their experiences.

When Bessie Vonnoh began her career in the early 1890s, she had a decision to make—compete with other sculptors (mostly men) for commissions to create monuments, soldiers on horseback, large castings of senators and the like…or think of another way to use her talent. And that’s what she did. She created statuettes, which she called Potterines. They were 12 to 14 inches tall, cast in plaster and tinted in pale colors. She sold them for $25 each.

Friends, society women and their children sat for her. She made enough money to rent her first studio and to begin casting her statuettes in bronze. Eventually, she constructed larger pieces for the garden, and then two figures of children that were placed in New York City’s Central Park as part of a memorial to Frances Hodgson Burnett, author of The Secret Garden.

Friends, society women and their children sat for her. She made enough money to rent her first studio and to begin casting her statuettes in bronze. Eventually, she constructed larger pieces for the garden, and then two figures of children that were placed in New York City’s Central Park as part of a memorial to Frances Hodgson Burnett, author of The Secret Garden.

Mastering the Medium

Bessie married the Impressionist painter, Robert Vonnoh. Her friend, Nellie Walker (1874-1973)—also a sculptor who worked with Lorado Taft—preferred to remain single. She once said that hers was “an ideal way to live, no husband to please, no children to disturb one, good friends to converse with, who will give help when needed, yet all the privacy one could wish for.”

Nellie learned to work with stone from her father, a stone cutter in Moulton, Iowa. At 19, she carved a portrait bust of Abraham Lincoln that was displayed in the Iowa Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. But she is best remembered for two works: her larger-than-life, bronze statue of Chief Keokuk that overlooks the Mississippi River in Keokuk, Iowa, and her dramatic depiction of Lincoln and his family entering Illinois for the first time that stands on the Lincoln Trail near Lawrenceville.

Illinois women artists like Nellie Walker resolved to master the techniques of their medium, wanting always to improve, learn a new style, even create unique styles of their own. Cecil Clark Davis (1877-1955) was a woman ahead of her time, excelling at sports and making light of convention, smoking with the men after a chic city dinner, and in 1899, insisted upon a platonic marriage when writer Richard Harding Davis proposed. She maintained studios in Chicago, London, Rio de Janeiro and Marion, Massachusetts, where she practiced constantly to enhance her

artistic abilities.

Look, Really Look

Look, Really Look

It was an instructor of art history at Chicago’s Art Institute that influenced an entire generation of artists in the Windy City. Kathleen Blackshear (1897-1988) introduced her students to non-European art and cultures, taking them to the Field Museum and the Oriental Institute to see the arts of Africa and Asia. They were as inspired by these fresh visual experiences as she was. It turned out that among her students were the creators of the Monster Roster and the Chicago Imagists, the novel Chicago art styles of the 1960s.

For her own work, Blackshear sketched and painted members of the African-American community in her hometown of Navasota, Texas, where she summered each year. In 1936, she broke racial barriers in Texas by exhibiting a portrait of two African-American girls at the Centennial Exposition in Dallas.

Another early artist and teacher, Ruth Van Sickle Ford, would tell her students to “look, really look” at the art. Then she’d add sarcastically, “Here, do you want to borrow my glasses?”

When you visit the exhibit at Lakeview Museum, please do look—and listen. Ruth Ford won’t be there to hand you her glasses, but if you bring your smartphone or iPad (or any device with a camera), you can connect to the Web and hear more about each work and its creator.

Come see what these women accomplished, learn their stories…and keep an eye wide open wherever you are for women-made art. a&s

When you find a work you love or a story that engages you, would you let us know? Email comments to the Illinois Women Artists Project at [email protected].