A born performer, Dexter O’Neal shares the gospel of funk with a growing audience across central Illinois and beyond.

A few years ago, he got a call on his cellphone: the band scheduled to play the Rhythm Kitchen Music Café had cancelled, and they needed a replacement. Dexter O’Neal agreed to perform, though he had no plan, no prepared material, not even a band. What he did have, however, was natural talent and a lifetime of experience—and he knew exactly how to pull it all together.

The singer/guitarist showed up that night with a group of music vets including Ron “Ocie” Jamison, Stan Burns, Tyler Dringenberg and Bryan Moore, and without a single rehearsal, they laid down a set of funk, soul and R&B so electrifying that by the end of the night, there wasn’t an empty seat in the house. Soon they had a name, and that raw energy would become a trademark of Dexter O’Neal and the Funk Yard, propelling the group to the forefront of central Illinois’ music scene. After decades of musical ups and downs, it is perhaps not the outcome O’Neal expected—but, he says, it has been one of the most rewarding.

A Push to Perform

O’Neal was born in a small parish near Ferriday, Louisiana, where “there’s nothing to do but farm and be quiet,” he jokes. Though Ferriday is home to just a few thousand residents, music fans may recognize it as the hometown of three famous cousins: Jerry Lee Lewis, Mickey Gilley and Jimmy Swaggart. It was against this backdrop of rockabilly, gospel and country music that O’Neal first cut his teeth on the American music scene—a hodgepodge of sounds rooted in jazz beats and hillbilly boogie.

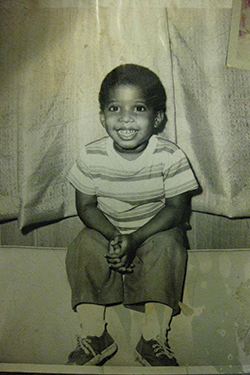

With his parents still in college, O’Neal lived for a time with his grandparents in rural Louisiana—they were the ones who first pushed him to perform. “I was three years old when I first sang in front of a church audience,” he recalls. It was obvious from that initial Sunday-morning performance that the kid had a gift. “There is no one in my immediate family who sings or plays,” O’Neal adds, smiling. “They looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, it had to be God, because we don’t have it!’”

Soon, he was singing in church on a weekly basis. “That’s how it started for me. By the time I was six, I was as comfortable performing as I was tying my own shoes.” Growing into his talent, he was pushed in different directions. “My grandfather wanted me to sing the blues, and my grandmother wanted me to sing in church,” he explains. “My goal was to please them both.”

Soon, he was singing in church on a weekly basis. “That’s how it started for me. By the time I was six, I was as comfortable performing as I was tying my own shoes.” Growing into his talent, he was pushed in different directions. “My grandfather wanted me to sing the blues, and my grandmother wanted me to sing in church,” he explains. “My goal was to please them both.”

By the age of five, O’Neal and his parents had moved to Bloomington, Illinois, where he continued singing in church and first picked up the guitar. Listening to his father’s record collection, he would try to pick out the guitar lines, and by the time he was 10, he could play songs like The 5th Dimension’s “Age of Aquarius.” “I would bring out my little Fisher Price turntable and listen to old Stylistics and Temptations 45s. I would go through them and see which one was hot.”

As his interest in music expanded, O’Neal would pick up a new instrument and play it for a short time, only to quickly leave it behind. When his lack of focus and interest in sports threatened to derail his vocal pursuits, his mother struck a deal with him. “She told me she didn’t care what instrument I picked up or put down, I could not stop singing—and that was that,” he explains. “She made me sing barbershop and choral music… jazz choir, too.”

A photograph of opera singer Luciano Pavarotti hung on his bedroom wall—with growing confidence in his abilities, that’s who O’Neal saw as his competition. “I had the picture on my wall with the word versus between his picture and my own,” he laughs. Soon, he was getting into community theatre and garnering state titles in vocal jazz and choral music, but it took a stint in the military to open his eyes to the possibility of a career in music.

Dexter Takes Flight

“This was my first interaction with people who were making music for a living,” O’Neal recalls of his experience watching a traveling Air Force band. When he asked how he could perform with them, they told him to join the service. “I was all in,” he laughs. “So I joined and went through basic training. I got to the point where they were going to assign me a job in the band… but there were no open positions.”

He got into accounting and ended up in the weapons unit, but O’Neal never stopped searching for an opportunity to return to music. When he heard about an Air Force talent show and its prize—a spot in one of the service bands—he was determined to win. At the first event, he tied for third place, allowing him to advance to the next round. “When I got to nationals, I was number one.”

For the remainder of his time in the Air Force, he traveled the world with Stars of Sound, a service band that once opened for Whitesnake at the height of their fame. “Whitesnake convinced me that I should be an artist,” he says, laughing at the unlikely pairing. “They said, ‘Dexter, you’re the real thing. You can do it!’” Nine months of touring with Stars of Sound gave him the experience he felt he needed to pursue a career in music. When he left the service at 21, “I started going after record deals, but there were no cell phones or Facebook back then, so I couldn’t call Whitesnake for help!” he jokes. “I had to carve out my own way.”

By the age of 23, O’Neal was earning royalties from “throwaway” songs he wrote for other artists, and record labels were flying him to L.A., Atlanta and New York—“grooming me to be the next Luther Vandross!” But while they promised the world, the labels ultimately could not deliver. Despite modest success over a decade of touring and recording, O’Neal had to leave his dreams of stardom behind—though he continued to produce music and perform back in central Illinois.

That transition, O’Neal admits, was difficult. “You go from having demos with Grammy Award winners to singing at [bars] to 50 people,” he shrugs. “You feel like you’re losing. You start to think… How long is it going to last? Am I ever going to ascend?” But he eventually began to see the benefits: he was getting more feedback playing smaller venues, which drove him to hone his skills further. “My school was on the large stage,” O’Neal says. “But my education came from the local scene.”

The Magic Trick

If you ask about his career, O’Neal won’t mention that he is a musician. Instead, he’ll talk about his day job as a computer architect at State Farm, or his love of basketball. Music is just part of life, as natural as breathing. “It’s such a part of me that I don’t think about it as a separate thing.” It’s his drug, and he has a complicated relationship with it.

“All of my band has the addiction,” he explains. “If I let myself, I would play every waking moment I possibly could.” He depends on his wife, artist Natalie Jackson O’Neal, to keep him in check. “She keeps me grounded. If the balance is off… she pumps the brakes for me.”

O’Neal describes himself as an introvert, though he admits that may surprise anyone who has seen him perform. “Sometimes people think an introvert is socially inept… all it means is that you are not ‘charged’ by people,” he explains. “That’s not how I refuel.” On stage, he channels the energies of his extrovert mother; for him, a performance is inherently spiritual. “I pray every time before I perform. I ask God to allow the people to see him through me… I’ve never not had that prayer answered.”

At the end of the day, O’Neal aspires to lift his audience up and away from their daily grind. With a smile, he recounts one moment of transcendence—just a single instance among countless others. “I had the guys hold a note, and while it droned on, I told the audience that I was going to perform a ‘magic trick,’ he says. “‘I’m going to make all of your problems disappear. I’m going to make you forget about your boss… your husband and the fight you had on the way to the club. As soon as this music stops, we’re going to forget all about it and have a good time.’”

The music stopped. And with a one, two, three… the beat dropped, and the crowd leaped from their seats—a roomful of world-weary patrons transfigured into mass cathartic jubilation. It’s a “trick” that now comes second-nature to the dynamic frontman. “You can’t tell me it’s not the music. I’ve seen the magic of it.”

The music stopped. And with a one, two, three… the beat dropped, and the crowd leaped from their seats—a roomful of world-weary patrons transfigured into mass cathartic jubilation. It’s a “trick” that now comes second-nature to the dynamic frontman. “You can’t tell me it’s not the music. I’ve seen the magic of it.”

An Ear on the Street

Some years ago, Dexter O’Neal was in New York City, amidst talks with Sony and RCA about a record deal. One evening, he says, he accompanied his cousin to an open mic night, and O’Neal performed a few songs. Afterward, they were called over to sit at a table—where the cousins found O.J. and Nicole Simpson, Terry Bradshaw, Bryant Gumbel and Greg Gumbel. “You can imagine the look on my face,” he laughs. “Suddenly, a drunk man comes up to me—pawing at me!—and tells me how great I sounded. He asked me to play with him, and being thirsty for opportunity… I said, sure, let’s go!”

As it turns out, the man he performed with that evening was the late Jerry Garcia—but it was months before he discovered it was “that guy from the Grateful Dead.” Over the years, O’Neal has found himself surrounded by some of the finest musicians in the world—from opening for the Temptations, to a run-in with guitarist Jeff Beck, to a rather hilarious encounter with Patti LaBelle—but in the end, he’s not concerned with anything but the present. “Duke Ellington used to say, ‘Keep one ear in the conservatory and the other on the street,’” he muses. “I believe it. If my heroes can evolve, I can evolve.”

As Dexter O’Neal and The Funk Yard prepare the release of their first album, they continue to garner critical acclaim while playing more than 130 shows a year to ever-larger crowds. In 2016, the group was even voted “Best Performing Artist” in Peoria Magazines’ Best of Peoria competition, but O’Neal is most proud of their benefit shows. “Last year, we fed 150 families in Peoria and helped raise over $150,000 for charities,” he notes.

Looking to the future, he hopes to continue to provide a joyful means of escape—sharing his passion, his addiction, his magic trick with all. “The music is for the audience,” he explains. “We just get to be the vehicle that it flows through.” a&s

For a schedule of upcoming shows or more information, visit dexteroneal.com.