The members of Tri-County Construction Labor-Management Council (TRICON), an association of union construction contractors and construction labor unions, approached Bradley University to perform an occupational demand and supply analysis to project the employment in the building trades for the next five to 10 years in the Peoria Metropolitan Statistical Area (Peoria, Tazewell, Stark, Marshall and Woodford counties).

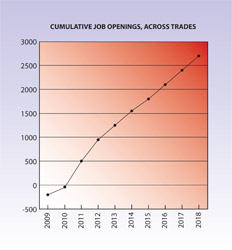

The review of anticipated job openings reveals substantial demand for labor in each of the trades. Looking at the combined impact of workforce needs, aggressive efforts to sustain staffing in the trades will be required. The anticipated staff losses over the coming years highlights the need to continue to recruit, train, motivate and sustain the kind of trades employees needed by contractors.

Editor’s note: The following was excerpted and adapted from “Occupational Demand/Supply Analyses and Market Assessment of Union Construction Contractors” by Drs. Rajesh Iyer, Kevin O’Brien, Bernard Goitein, and Danielle K. Pasko of Bradley University, a report published in June 2009.

Demand Factors: Aging Workforce

One of the two major sources of demand for workers in the construction trades are those workers needed to replace retirees. Like the workforce in general, the construction workforce is aging, and the effects of this trend will be significant.

In 2005, the Construction Labor Research Council (CLRC) reported that the baby boom cohort will reach retirement age over the 2005-2015 time period. The number of males 55 to 64 years old will increase from 11.6 million to 18.3 million, and the number of new retirees will reach levels not seen before in the United States. The construction trades, like all industries, will feel the impact of this unprecedented outflow of workers from the labor force.

Trends in Construction Employment

Trends in Construction Employment

The other major source of demand for workers in the construction trades is the growth in employment related to trends in construction activity. Since most of the local building trades are primarily employed in nonresidential projects, the trends in this sector must be analyzed as well as construction employment in general. The complicating factor is the current recession and how it will affect the local economy. Specifically, how much longer will it last, how much more will construction employment drop and how long will it take before construction employment in the Peoria area returns to pre-recession levels?

In the current recession, the downturn in the nonresidential construction sector of the economy began in mid-2008. Since that time, nonresidential construction has declined by seven percent. This is comparable to declines in recent recessions at this stage of the downturn. In the 1982 recession, nonresidential construction fell by almost 28 percent before the sector began to expand again. The same figure for the 1991 recession was a drop of 31 percent, while the decline for the 2001 recession was 25 percent.

Given the experience in previous recessions, further declines are expected. A January 2009 report by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) projected a decrease in nonresidential construction of 11 percent for 2009 and five percent for 2010. These estimates did not include the effect of the Obama stimulus package, which may blunt the declines. Including the previous seven percent decrease in nonresidential gives a projected decline of 23 percent for the whole recession.

In March 2009, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development projected a 17.8 percent drop in nonresidential construction for 2009, with a 6.4 percent decline for 2010. Again, including the previous drop in nonresidential gives a projected decline of 31.2 percent in nonresidential spending over the entire recession. This larger projection even includes the effect of the Obama stimulus.

In terms of employment, at the Peoria metro level, data was not available for the 1982 recession. In the 1991 recession, construction employment decreased by 31.1 percent from its peak level. In the 2001 recession, local Peoria construction employment actually increased.

From both national and local data, the current recession appears to be following the 1991 recession most closely. In the current recession, construction employment had already declined 9.8 percent by February 2009 and 21.7 percent from its peak level. If the 1991 pattern holds, local construction employment can be expected to fall at least another 10 percent. Thus, the market will not reach its low point for at least a year, and in the projections for the local unions, it will be assumed that employment demand will fall another 10 percent for 2009. Given the expected sluggish nonresidential construction market for 2010, employment growth should fall by another five percent if national patterns are followed.

How long will it take local construction levels to reach pre-recession levels? Nationally, for the 1991 recession, 86 months elapsed before employment recovered to pre-recession levels. At the local Peoria level, the recovery only took four months to achieve pre-recession levels. Given the severity of this recession, the local employment recovery should take much longer than four months.

One reasonable estimate would be a symmetric recovery. Given that the recession led to three years of employment declines, it would then take local construction employment three years to recover to its pre-recession (2008) levels. In recent recessions, the local market has not taken this long to recover. A compromise estimate would be two years for the local construction market to recover to its pre-recession levels. Two complicating issues for this forecast are the unique severity of this recession and the local Peoria effects of the Obama stimulus package. After the recovery, the projection is that employment growth will return to

long-term trends.

Supply of Workers to the Construction Trades

Supply of Workers to the Construction Trades

While the number of retirees will be accelerating in the near-future, the growth in the labor force will be slowing. According to the national Construction Labor Research Council (CLRC) report for the U.S. as a whole, the labor force will only grow 1.1 percent per year in the 10-year period starting in 2005, the slowest growth for the labor force since the 1960s.

What about the labor supply needs of the construction trades? The CLRC study estimates that the industry will need 185,000 new entrants per year to meet the demand for workers from both retirement replacement and employment growth from new spending. Construction employment is projected to increase by 1.6 percent per year. Recall that the labor force over this same period, which can be viewed as labor supply, is projected to grow only by 1.1 percent. Thus, it will be a challenge for the construction trades to generate enough new supply of workers to meet future demand.

Will an actual shortage of construction workers occur? An actual shortage, i.e., a literal shortage of bodies, will probably not occur. If a shortage occurs, it will show up as a shortage of properly trained, skilled, productive workers. As listed in the CLRC study, there are a number of factors that will influence the supply of workers needed in the construction trades. One is the level of immigration to the United States, particularly the rapid growth of Hispanic immigration and the growth of Hispanic workers in the construction trades. A second factor that will affect the needed supply is increased productivity in the construction industry, which will lessen the need for workers.

A third factor is the type of training needed by new entrants. According to the CLRC, there are currently no reliable figures for the number of workers being trained in the construction industry and the adequacy of their training. In 2005, by one count, there were 225,000 persons in government-registered apprentice programs, but this figure is not complete and does not indicate how many people actually complete the training. Yet some general conclusions can be made about the state of training in the construction trades. First, most of the training is done in the unionized portion of the industry. Secondly, of those workers who receive formal training, the amount of training received differs greatly by the type of craft trade being examined.

While the above discussion concerns national trends, what about the factors affecting supply in central Illinois? Some concerns are examined in an article by Bashir Ali in the Workforce Network News in July 2008. Over the next five to 10 years, there is an estimated labor shortage in central Illinois of 7,000 to 18,000 workers. In central Illinois, only 50 to 60 percent of high school students meets or exceeds standards as defined by the Prairie State Achievement Exam. The figures are worse for students in inner-city schools. In addition, there are constant concerns about skill and employability traits (attendance, work ethic, etc.) of the workforce. All these factors will present a challenge for developing the supply of workers needed for the construction trades in the Peoria area. iBi