History is a funny thing. Many of us hated history class when we were in grade school, having to memorize the dates of wars and various occurrences that someone in the school system seemed to think we should know. Yuck, boo-ring! Who cared whether it was General Cromwell who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo…or was it General McArthur? And what in the world was Napoleon doing in Iowa anyway? That was then, and this is now.

But now that I am in my sixth decade on this earth, history has a different look. Now, for some reason, I do want to know what happened; when, where and how it happened; and who was involved. Then I want to know why it happened and what it meant to people at the time. I find myself looking to see if the event has relevance to today. If this had been told to me when I was in school, I probably would have said, “Okay, you want to go play some ball?”

I was born to parents who were, in large part, skeptics. Dad was the more obvious skeptic. He always wanted to know the “what” and the “how” of things, and he was pretty strong on trying to figure out the “why” as well. He would delve into just about everything that piqued his interest, and when he finished, he could pretty well explain it. I can look at my siblings and see that that gene was definitely passed along to each of us. My oldest brother, Jim, is Dad all over again, except in the mechanical skills area. He wouldn’t want to know how to fix an automobile, but turn him lose on genealogy, computer systems, or a historical project, and he sparkles like the Hope Diamond.

I was infected with that same disease at birth, and when I enlisted in the Air Force, my fate was sealed. I wanted to be a photographer, then a military policeman, but nooo…they sent me to intelligence analyst school. What does an intelligence analyst do? He looks for details that are often scattered and hidden in all sorts of places, tries to recognize which bits are related, and then tries to fit them together to tell the real story in the details. I have had to deal with this nagging need to go for the details ever since.

And so, when I first heard that James Cash Penney had come to open a store in Chillicothe, I became curious. A friend had mentioned that event several times, adding that Penney had been the guest speaker at the dedication of the remodeling of the First United Methodist Church in 1950. I had to find out why he would have done that.

I learned that Penney had somehow been involved in business with a man from Chillicothe, Thomas M. Callahan, out in Colorado. That was enough for me to want to know the details. And the details I found tell the story of Chillicothe, Thomas Callahan and J.C. Penney.

The Callahans of Chillicothe

The Callahans of Chillicothe

Born in Ireland on June 24, 1828, Celia A. Hood immigrated to the United States and came to Peoria County in 1846. She married Thomas C. Callahan in Peoria in 1848, and they set up their home in Chillicothe. They had seven children, four boys and three girls.

The Chillicothe Independent and Chillicothe Bulletin newspapers have revealed considerable information about the Callahans. When Celia Callahan died in 1908, the death notice commented on her high degree of honor and integrity, and lauded her for raising her children to be well-respected adults, despite having to do so alone. There is no mention of the absence of her husband, Thomas; it has not been discovered why he was not around to raise his family after the birth of his son, Felix, in 1868. There is indication that he was a “tinker” by trade and operated a pushcart in Chillicothe. Webster’s College Dictionary defines a “tinker” as “a mender of household utensils (as pots and pans) who usually travels from place to place.”

Those of you who can recall the character of Mr. Haney from the sitcom Green Acres have an idea of what a tinker might actually have been. There is no clear record that Callahan was the “Mr. Haney” of Chillicothe, but it might suggest why Mrs. Callahan, a strong Catholic woman, was left to raise their children by herself.

Celia Callahan rented a small frame building on the west side of Second Street, located approximately where the Commerce Bank drive-thru is now situated. It appears she began her dry goods business in the late 1860s or early 1870s, but there are no newspapers available prior to 1883 that could confirm that. The building was destroyed in the October 30, 1890 fire that wiped out over two-thirds of the Chillicothe business district. Callahan purchased land across the street and soon re-established her business in the building that now houses Covered Wagon Gifts, at 1042 N. Second Street.

The 1880 census for Lincoln, Missouri shows that Celia’s son, Thomas M. Callahan, was a 23-year-old school teacher, and his sister, Julia, was also teaching school in Lincoln at age 19. It indicates that they were boarders at the home of Dr. Z.T. Magill and his wife, Mary. The Callahan family headstone in the Chillicothe Cemetery shows Mary J. Magill as being buried there, confirming that Thomas and Julia were living with their sister and brother-in-law.

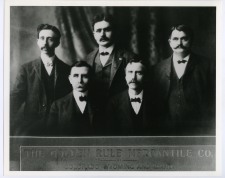

Thomas M. Callahan married Eliza Alice Barnett in Humansville, Missouri, in 1886, and later moved to Longmont, Colorado, north of Denver. They opened a dry goods store called “The Golden Rule Store,” which reflected Alice’ strong religious upbringing. Callahan took on a partner, Guy William Johnson, to help expand the business, and together, they began building a chain of dry goods stores across Colorado, Nevada, Wyoming, Idaho and Utah. Callahan became involved in many business activities in Longmont, and his reputation as an honest and skillful businessman grew steadily.

An Entrepreneur Gets His Start

An Entrepreneur Gets His Start

In 1897, a young man left Hamilton, Missouri, on the advice of his doctor, who said he was developing signs of tuberculosis and recommended that he move where the air was clean and clear. He first went to Denver, but soon moved to Longmont and decided to open a butcher shop. He happened to acquire the fresh meat business from the head chef at the Longmont Hotel, but when it came time to make the delivery, the chef demanded a fifth of whiskey as gratuity for placing the order. The young butcher was very religious, having been raised by a strict Baptist preacher, and was torn by the idea that he would have to bribe the chef to get the order, but he gave in. When it came time to renew his order, the chef again demanded the bribe of liquor. This time, the butcher refused to pay, and the chef took his business elsewhere. The loss of the hotel business doomed the fate of the young butcher’s business, and by 1898, he had to close his shop.

This young man had become known in Longmont for his high moral character, and he was offered a position as a retail clerk in the Golden Rule Store operated by Tom and Alice Callahan. He was James Cash Penney, who had worked as a clerk in the dry goods store in Hamilton, Missouri, when he was just 15.

Callahan and Johnson had established a plan to develop their chain store business. They would seek young men with strong moral character and train them to run the stores on their own. Callahan offered Penney a position in the Evanston, Wyoming, store in 1899, where he earned $50 a month. Six months later, Penney married, and he remained at the Evanston store until 1902. That year, Callahan offered Penney a third partnership in a Golden Rule Store to be opened in Ogden, Utah. He refused, but offered instead to open a store in Kemmerer, Wyoming, where it seems that he had relatives in the area. One problem faced Penney. He did not have the money to buy into the store as a partner.

Callahan and Johnson loaned him the necessary money to secure him a partnership, and Penney opened the Kemmerer store and moved into the upstairs apartment with his wife and first child. Penney then switched the method of business that was typical for the day. Back then, most people were paid once a month, making it necessary for most businesses to maintain accounts on a 30-day credit plan, but Penney decided to switch to a “cash and carry” policy. He was told that he would go broke in a short time. Penney promised to provide a customer with the highest-quality goods available, to be paid for at the time of sale. If the customer was unhappy or the product failed, Penney would replace it with a new item without additional cost to the customer.

At the end of his first year, Penney’s store recorded annual sales of nearly $30,000, with a net profit of over $6,000, and the Golden Rule Stores immediately changed their policy to “cash and carry.” Penney opened several more stores, and by 1907, the chain consisted of 18 stores in five states. That year, Callahan and Johnson decided to sell their dry goods business to Penney, who was eager to expand into every city in the U.S. and continued to operate under the Golden Rule name.

From comments published in the Chillicothe Bulletin, Tom Callahan made regular trips to New York and other major eastern cities to buy goods for his stores. Many of these trips included stops in Chillicothe to visit his mother and sister. When Alice Callahan named the first store of the chain “The Golden Rule Store,” her mother-in-law changed the name of her Chillicothe store from The Callahan Store to The Golden Rule Store. Meanwhile, Tom’s sister, Julia, opened a store in Princeville in the early 1900s, after she returned to Illinois and married Edwin Middlebrook.

Penney’s Dream Expands

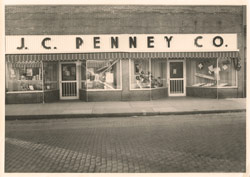

J.C. Penney pursued his dream of expanding his chain across the country, adding eight stores in both 1909 and 1910. In 1913, he incorporated the business under his own name, and each store was now a J.C. Penney store. He did not immediately rename all of the Golden Rule Stores; instead, he would change the name as he remodeled existing stores. Penney continued to expand, adding new stores each year.

Penney’s business expanded by 28 new stores in one action when he purchased the Yakima Cash Store chain, which extended from Colorado through Utah and Washington. It is not surprising that Penney made such a bold move to expand in this manner when it is explained that the Yakima chain had been established in the mid-1900s by none other than Thomas M. Callahan and his partner, John L. Barney.

Like Penney, Barney had been an employee of Callahan’s in a Golden Rule Store for 13 years, and in 1903, he opened the Barney-Callahan Store in Montpelier, Idaho. Barney operated that store until 1909, when he moved to Yakima, Washington, and opened the first Yakima Cash Store. The Yakima stores continued to be major suppliers of dry goods until the chain was sold to J.C. Penney. By the end of 1925, J.C. Penney, Inc. had grown to 674 stores with gross sales of over $91 million. In all, Callahan established and then sold J.C. Penney a total of 46 dry goods stores.

Thomas Callahan was born and raised in Chillicothe, and he maintained his connection by supporting his mother and younger sister through his very successful business from 1892 to 1929, when the last Golden Rule Store was closed and converted to a J.C. Penney store. Chillicothe’s connection to Penney’s success is confirmed by history. When Callahan returned to Chillicothe in 1929 to work for several months with his sister to close out the final Golden Rule Store, he was joined by J.C. Penney to make the official change-over.

Another confirmation of the significant contribution of Thomas M. Callahan to the success of J.C. Penney came from Penney himself. In 1949, the Chillicothe Methodist Church was remodeled, and the following April, the church’s men’s club held a dedication dinner and invited J.C. Penney to be their guest speaker. Three hundred people attended and heard Penney tell them of his life’s experience and the importance of his faith in his success. In that address, Penney gave clear recognition of the influence and help he had received from Chillicothe’s own Thomas M. Callahan. iBi

Gary Fyke is a former mayor of Chillicothe and member of the Chillicothe Historical Society.