Consumer demand for quality and security is fueling a return to a local food system.

Drive ten miles in any direction from Peoria, and farmland will envelope you. Drought aside, “the corn row corridor walls of cornstalks” still rise like Sandburg’s words, stretching far beyond the eye. Midwestern soil lends itself to the cream of the crop—our topsoil in particular, is “some of the finest cropland in the world,” notes a recent National Geographic feature. Here in Illinois, corn and soybeans define the prairie landscape, having increased from 60 percent of the state’s total cropped acres in 1950 to over 90 percent in recent years. And most of that which is yielded is exported, leaving the state—and its soil—in a quandary.

Last year’s Central Illinois Green Expo welcomed renowned food analyst Ken Meter, president of the Crossroads Resource Center in Minneapolis, to Greater Peoria. During his visit, Meter outlined his study of central Illinois’ food system—an examination commissioned by the Edible Economy Project, a collaborative effort to build connections between local food producers and consumers. He found that central Illinois consumers purchase $4.3 billion of food each year—more than 90 percent of it imported from outside the region.

Meter calculated that if our region’s consumers purchased just 15 percent of their food directly from local farms, those farms would earn $639 million in new income. But that figure is a far cry from current local expenditures, which stand at about three percent. And while the region is capable of producing over 80 percent of the area’s total consumer volume, according to FamilyFarmed.org’s report, Building Successful Food Hubs, it currently produces just six percent. All told, Meter suggests that the 32 counties in his study are losing $5.8 billion each year through the export of local production and import of our mainstay food supply.

How can we tap this potential market? According to a recent study by the research firm Mintel, nine out of 10 consumers would buy local produce if it were conveniently available. So, why isn’t it readily available? And how do we change that? Moving forward starts with an examination of the local infrastructure.

Reading the Land

The concept of local food is nothing new. While just one percent of Americans live on farms today, a century ago that figure was closer to 40 percent. These farmers were responsible for the majority of the food consumed in the country. Few foods were processed or packaged, and fresh produce and dairy products typically traveled less than a day to market, while consumption was dictated by local seasonality. But after World War II, the U.S. food system shifted, suggests a recent USDA report. National and global food sources replaced local ones because suddenly, anything was possible. Lower transportation costs, new refrigeration options, technology that enhanced regional specialization, and expanded free-trade agreements fueled consumers’ ability to demand essentially anything, and large-scale factory farming led to the production of huge quantities of cheap food.

In the face of regional specialization, “many local farmers could no longer produce competitively,” the report continues, especially in light of exotic exports allowing access to increasingly bigger and better fruits and vegetables year-round. California became known for almonds; Honduras: bananas; Florida: oranges; Idaho: potatoes; and so on. Life became, in many ways, luxurious, dependent on exports.

These trends transformed the nation’s agriculture and food industry. Small- and medium-sized farmers were perhaps hit hardest, as value chains became driven by larger players. Illinois’ current infrastructure, for example, includes just a handful of post-harvest aggregators and processing facilities that can support small- and medium-sized growers. Limited channels prevent these smaller growers from getting their crops to distributors (like Kroger), wholesalers (like Sysco), and contract food suppliers (like Sodexo), which together constitute 80 percent of wholesale distribution and 99 percent of total food sales, according to the USDA. Direct-to-consumer channels like farmers’ markets and CSAs, or consumer supported agriculture, currently account for less than one percent of total produce purchased in the United States.

But recently, consumers are returning to the idea of local food—defined as “less than 400 miles from its origin, or within the state in which it is produced,” according to the Food, Conservation and Energy Act of 2008. Some say the movement is sparked by fear, as an unpredictable economy and global conflict have led to questions of how domestically secure we are in our own fuel and food. Some say the costs of transportation affects the bottom line, and we must buy local to reduce those costs. Other consumers are simply considering the geographic dimensions of their everyday choices in an effort to be “greener.” In any case, a shift to a more local food system can provide access to safe, healthy and secure channels for fresh food. There is also an economic incentive behind the shift.

The Local Dollar

“The current system takes wealth out of our communities,” Meter asserts. “Local foods may be the best path to economic recovery.” In the report, he suggests that food can be an economic engine. “The best path to economic recovery right now,” he explains, “is having more community-based food solutions and buying less into the industrial model of raising foods.”

But some disagree, arguing that today’s high crop yields and low costs reflect gains from specialization, trade and large-scale economies. Some even say the return to a small-scale agricultural model could be economically catastrophic. The authors of the controversial book, The Locavore’s Dilemma—a counter-argument to the bestseller, The Omnivore’s Dilemma—argue that increased levels of food security are due to the evolution from small-scale subsistence agriculture to international trade among large corporate producers. And with an ever-increasing global population, they suggest that we need these economies of scale to continue to make advances in technology, yields and food safety.

MacClean’s magazine summarizes the book’s argument as “the belief that the only way to feed an ever-growing global population is to produce more food on less land with fewer resources, which means the family farm will continue to die a gradual death in favor of corporate agribusiness… [They] argue that if we were still using 1950s technology to produce our food, we would need to plow an extra land mass the size of South America just to feed the world’s population.”

There are, however, solid numbers on the opposing front. Since the average fruit or vegetable purchased in the Midwest travels 1,500 miles from farm to plate, there are obvious environmental benefits to buying locally. Money spent locally also creates jobs—2.2 for every $100,000 in local food sales, according to a report by the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Put another way, a 2011 USDA report found that fruit and vegetable farms selling to local and regional markets employ 13 full-time workers per $1 million in revenue, while those not engaged in local sales employed just three full-time workers per the same.

Buying local also increases the average farmer’s income by cutting out the middle man. “The farmer now gets less than 10 cents on the retailer food dollar,” explains The Good Earth Food Alliance, a central Illinois-based CSA. Buying directly from the farmer allows them to receive the full retail price so “families can afford to stay on the farm, doing the work they love.”

It also benefits the broader business community, suggests Terra Brockman, founder of The Land Connection. “When people buy their food locally, that money doesn’t just go to the farmer and that’s the end of the story… That farmer then buys from the local hardware store, puts it in the local community bank, or spends it at the local diner… [it] keeps cycling within the community.”

Connecting Farmers & Farmland

Connecting Farmers & Farmland

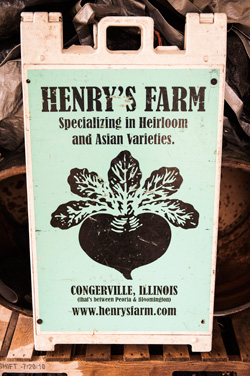

An author and farmer by trade and heart, Brockman comes from a long line of Illinois family farmers. This upbringing, in addition to having lived and worked around the world, adds credibility to her belief that Illinois farmland is capable of growing the best food in the world. Her family, too, is living testament: Brockman’s sister, Teresa, raises over 70 varieties of fruits in Eureka, and her brother, Henry, over 650 varieties of vegetables on 10 acres nearby.

In her own words, “[Henry’s] farm is nestled… in the Mackinaw River Valley, a mecca of diverse, organic and sustainable farming hidden in the rolling hills of a small river valley… surrounded by oak and hickory forests.”

Motivated by the diversity of this land, Brockman is an advocate for sustainable agriculture, as evident in her book, The Seasons on Henry’s Farm: A Year of Food and Life on a Sustainable Farm. She long ago recognized that among the many pieces of the local food puzzle, the farmer must come first. Thus, she incorporated The Land Connection as a nonprofit in 2001, with a mission to preserve and protect farmland and help train new farmers. Brockman pours her passion into a year-long course designed to assist anyone wanting to launch and run a successful, diversified farm. The program features business planning seminars, field days and one-on-one mentorships with area farmers.

One of the challenges today, she explains, is that fourth- and fifth-generation farm families are struggling with succession planning, as many elderly farmers’ kids and grandkids have left to pursue different careers. “What’s going to happen to that farmland?” she asks. “We’re trying to influence that answer. Part of that land could be long-term leased, or bought by new farmers or… investors who want to help the local food system and then rent to new farmers. We are trying to make people aware that they have options—they don’t just have to sell.

“We feel that The Land Connection is the first piece, without which you can’t really have the other pieces of the food system,” Brockman explains. “If you don’t have the prime movers—the actual farmers on the ground and the farmland that they use to grow local foods—then you’re not going to get very far down the local food path.”

Building a Hub

The Edible Economy Project, steered by the Economic Development Council of the Bloomington-Normal Area, Heartland Community College (HCC) and The Land Connection, grew out of a recognition that central Illinois needed to scale up its local food economy. The long-term goal is to provide farmers access to an expanded market and local consumers access to fresh, healthy local foods. The project’s first step is to build a food hub network, which would allow smaller producers to reach crucial wholesale markets by providing the missing link in the food system chain. The plan for central Illinois, says Catherine Dunlap, associate director of HCC’s Green Economy Initiative, is to create what is called a minimal food hub.

“Instead of having one large facility where all the crops go to get processed, the food hub will be on site at a farm,” she explains. “We’re completing a survey of people interested in the project. To participate, they must have a central location, be close to an interstate, and have loading docks and cooling facilities.”

This ambitious goal got a bit easier with the recent receipt of a $99,000 USDA Rural Business Enterprise Grant to aid in developing three of these hubs. Once they are established, the Edible Economy Project will help coordinate the transportation of farmers’ crops from these central locations to interested buyers. The idea, explains Dunlap, is to serve as a matchmaker among the coalition of farmers, food hubs and buyers. So far, she says, the interest has been overwhelming, with local universities and colleges, grocery stores and restaurants among the interested parties.

The group is also fast-tracking a co-op grocery store, Green Top Grocery, set to open in Bloomington by the end of next year. It will coordinate classes in conjunction with HCC to educate consumers on the importance of buying local, among other topics. But farmer education is also key. Many small farmers want to expand, but don’t have the knowledge or time to do so, Dunlap explains. “Our group is serving as a facilitator to help coordinate these efforts.”

For the Long Haul

About six years ago, the Illinois Stewardship Alliance, a membership-based organization that advocates for local food systems, brought a group of farmers who were marketing to the Springfield area together for a discussion.

“We wanted to see what we could do to support small and diversified farmers in growing the local food system,” says Lindsay Record, executive director. “One thing that came out of that discussion was the need for increased public awareness.” The next year they launched the “Buy Fresh, Buy Local” central Illinois chapter, part of a larger national campaign, which publishes an annual guide of retailers, restaurants, distributors, farms and markets.

One sponsor of the local chapter is the Spence Farm Foundation, owned and operated by Marty Travis and his wife, Chris, alongside Spence Farm—the oldest family farm in Livingston County. They promote sustainable farming and educate the public on the value of small farms and farm heritage. “Knowing where we’re from helps us to know where we’re going,” explains the foundation’s director, Carolynne Saffer, noting that the Travises lead by example.

“They’ve refined their succession planting and the rotation of different plants on their own land, and they work, always, toward a long-term vision of where they want to be,” she says. Long-term planning is also a cornerstone of The Land Connection’s Farm Beginnings course. Brockman individualizes the program for each prospective farmer, and requires students to present their three- or five-year business plans at the end of the course.

Cooperating for Comparative Advantage

Brockman also promotes sustainable farming, pointing to their family farms as examples of how to produce without chemicals, and how to plant a variety of crops—models that are not only healthier, but can generate more revenue for farmers.

“One of the main advantages of planting with diversity in mind, is that if you have failure with part of your crop, you’re more likely to have some of your crops be successful,” Safford explains. Amidst the worst drought Illinois has seen in over half a century, the benefits of this approach are easy to fathom.

So, why don’t more farmers vary their crops? It goes back to the idea of regional specialization. Although some alternative crops may grow quite well in Illinois, they may not enjoy a comparative advantage under Illinois conditions. For example, some types of edible dry beans grow well here, but have a comparative advantage in other regions of the country. This is not to say that they necessarily grow better there; rather, they are capable of producing more income than other crops grown there. Transportation costs and proximity to processing facilities must also be factored into a crop’s agronomic suitability—one of four objectives of plant breeding— before determining whether or not to grow it. (The other factors include yield, quality, and resistance to pests and disease.) Considering all the factors, it’s easy to get deterred from growing anything but that which yields the most product for the best price. But that concept is flawed.

“We need new entrepreneurs who are willing to bridge some of the gaps in the local food system,” Record says. “We’re finding that the growers can grow it, and there’s a growing demand where restaurants and institutions want to buy it, but that connection from the farmer to the buyer is not direct. We have such an efficient global food system, where you can get things overnight from across the country—or even across the world—but it’s not that simple to buy something from your own backyard.” One of the problems, she explains, is that many farmers don’t use invoices, want to be paid [up front], or don’t do their marketing cooperatively, so buyers must purchase from each farmer individually.

But Chris and Marty Travis, she explains, have developed a model that challenges this notion, featuring 25 farms that market cooperatively in farmers’ markets, restaurants and a CSA. A recent survey by the Illinois Stewardship Alliance found that only half of central Illinois farmers have a product list—an essential link between farmer and consumer—but the Travises depend on it. They send a weekly email with product availability to about 200 potential buyers.

“They’ll deliver the products to Chicago, Champaign-Urbana and Springfield, and they provide one invoice to the restaurant or business, cutting checks individually to the farmers,” says Record. “We need more people like them, but it seems to not be an easy thing to duplicate. It’s a lot of work, and you have to have this certain willingness to work together. In any business, people sometimes view each other as competitors, and… there can be some hesitation to [work] together.” Education will change that, she says, but we also need to focus on the consumer.

Know Your Food, Know Your Farmer

Dan Grillot sometimes gets into trouble for his bluntness. A regular vendor at the Peoria Heights and Peoria RiverFront farmers’ markets, he puts it this way. “If you want to buy your produce from [a large grocery chain], that’s fine. But where does it come from? What’s sprayed all over it? How long has it been sitting in the warehouse? … What’s it going to taste like?”

At the two markets alone, Grillot and his wife, Miseon, “sell just about everything they produce” on their 20 acres in Canton, DMG Bee Haven Farm, including several varieties of “tomatoes that taste like tomatoes.” As customers line up to try the Russian heritage, giant heirloom and tart grape varieties, their testimony backs his word.

Being a small farmer, sometimes his prices are a bit higher, he admits, but they have to be in order to make ends meet. “Do I feel bad about charging a premium price? No, not at all,” he says. “Do I sell a superior product? Yes—you pay for what you get.”

Anything the Grillots don’t sell at the markets, they donate to The Salvation Army—some weeks up to 30 pounds of food. There is more supply than demand at the farmers’ markets, and this year, that news prompted a program for those who qualify for federal food subsidies to take advantage of the RiverFront Market’s fresh foods through its LINK card program. Although news in early August that the grant money nearly ran dry is further evidence of gaps in the local food system infrastructure, a fund has since been set up at the Community Foundation of Central Illinois to serve the same function.

Simply put, in order for the food system to become truly local again, more people need to jump on the bandwagon. Saffer offers an example commonly used by the Spence Foundation in one of its classes for kids. “We hold up two apples and say, ‘This apple came from Johnny’s backyard, and he’s your next-door neighbor. This other apple came from Washington State. They’re both very tasty. But Johnny will benefit directly from you paying $4 per pound. Meanwhile, the other apple has to travel all the way from Washington—there are distributor fees, truck driver fees and grocery store fees. Yes, those people need to make a living too, but when you’re actually purchasing directly from your neighbors—the people you’re connected to—it keeps the money local and it drives economic opportunity.’”

While attendance at farmers’ markets is up nationally, according to the USDA, most run only about 20 weeks of the year, which can be deceiving. “Most people think they can only eat local foods for six months a year. I eat local foods 12 months a year, and it’s actually not that hard,” Brockman stresses.

She believes that once the infrastructure is in place, consumers will realize the extensive potential of local food. “The food hub will make it easy to store crops year-round, especially root vegetables… and if we have people producing enough of them and a facility where we can keep them at the right temperature and humidity, it’s not hard at all… The food hub will become a packaging place where you can dry, freeze or can food for year-round consumption.”

Urban farming initiatives are also increasing consumer awareness. Tazewell County may soon allow residents to own backyard chickens, pending a decision on whether to allow certain types of agriculture on residentially-zoned property. Meanwhile, the rise in gardens—both personal and community—is another sign of commitment to the urban farming movement. It’s estimated that the addition of a garden can increase the value of your home by five to seven percent, and save $530 in annual expenses, depending on what you plant, according to John Robb of resilientcommunities.com.

For those without their own yards, community gardens abound: an organic garden on Forrest Hill offers four-by-eight foot plots at $10 a pop; kids learn how to grow produce near Logan Recreation Center; the West Bluff Community Garden is tended by local volunteers; and the Renaissance Park Community Initiative tends a new garden on Main Street, among others.

From Farm to Table

From Farm to Table

The trend for fresh food is contagious. Chefs surveyed by the National Restaurant Association in 2010 ranked locally grown produce the No. 1 menu trend. Eighty-nine percent of fine-dining operators serve locally sourced items, and nine in 10 believe demand for locally sourced items will grow in the future.

For Libby Mathers, it’s simple. “When you can get fresh, locally-produced food, not only does it benefit the local economy a lot more, it’s better. It tastes better, it’s fresher, the flavor profile’s better, and the quality is better.”

A Delavan native, Mathers returned home nine years ago with a dream to open a restaurant with “great food and great ingredients.” Aided by Cameron Urban, an innovative chef who has worked with June’s Josh Adams, the Harvest Café’s forte is fresh, locally-produced food. The restaurant depends on local suppliers—Meadow Haven Farms in Sheffield, Jenkins Farms in Low Point, and the Hintz Family Farm in Delavan—but its real key is spontaneity, Mathers explains. Spontaneity is necessary to incorporate unexpected surprises, such as a random 20-pound delivery of a local forager’s ramps—“a delicate, mildly garlic shallot flavor that makes a great accompaniment to a lot of dishes”—or the occasional load of watermelon that a farmer sometimes drops off at the back door, Mathers laughs. Mathers’ and Urban’s commitment to quality fuels the menu: the beef is prime and like the pork, artisan-raised. The chicken is free-range and organic, from Bradford, Illinois. The fish is flown in twice a week—fresh and tagged sustainable. “It makes a tremendous difference,” Mathers says.

Josh Adams, too, is riding a receptive response for his commitment to quality local foods. His restaurant, June, in Peoria Heights is another farm-to-table venture. Adams insists on baking all goods and butchering all meat in-house, and canning and preserving their own seasonal produce. He’s also planning to construct a geothermal greenhouse so they can grow their own produce year-round. For now, he relies on close relationships with local farmers to fuel their seasonal menu. And he’s not alone.

The Illinois Stewardship Alliance is working to increase other restaurants’ purchases of local foods through its Local Flavors campaign. “We dreamed up this idea of providing an opportunity for farmers to sell directly to restaurants,” Record says. “We felt the consumer demand was there… but it was really about getting the restaurants to [commit] to regularly source locally produced foods…, understand seasonality, and develop those crucial relationships with the farmers.” The program started in Springfield and has since spread to Champaign-Urbana, Bloomington-Normal, and this year, Record hopes, to Peoria.

“We’ve seen a definite increase in commitment. There are some chefs who have been using [locally sourced foods], but they’ve upped their commitment as a result of participating in the series. I also have anecdotal evidence from farmers that say, without a doubt, the Local Flavors series has contributed to their bottom line.”

The chefs with whom Record has spoken “want to know who they’re buying from. They like to be able to have a rapport with this person face to face… Some farmers are now bringing in a seed catalogue to the chef in the winter and asking, ‘What do you want me to grow next year?’ So they can really customize [it]… But those relationships have to be in place for those conversations to happen.”

A Win-Win?

“The great thing about local food is that it touches so many different parts of the economy,” Dunlap explains. “If it shows up in… restaurants, then you’re eating more, if you’re buying it from a farmers market or a CSA, then you’re getting more benefit from it. And it’s reducing our carbon footprint.”

Mathers believes that, over time, this awareness will continue to grow. “This is one area where we could hearken back to Europe,” she muses. “When you come in to eat, it should actually be about the food, visiting with your dining partner and enjoying the freshness of the meal.” In line with this thinking, the Harvest Café has no TVs, and Mathers keeps the music at a low level so conversation prevails. She recalls simpler days.

“When I grew up, every night my mom made us dinner, and she got everything from [a local butcher] in Pekin… The explosion of fast food and processed food… has taken too large of a profile in the way a lot of Americans eat. But I do think this generation [wants] to be healthier and eat better.” Often overlooked, local food has the potential to address the costs associated with rising obesity rates and other problems linked to the consumption of over-processed, nutrient-less food, Mathers suggests.

And while there’s some disagreement as to the long-term effects of a return to local food and the ability to feed a growing global population with less reliance on the commercial agriculture system, most supporters take a balanced approach—striving to find that equilibrium. “We’re hoping to share the concept of sustainability, so people want to build a community focused on diversity in farming,” says Saffer. “We accept that commercial ag is commercial ag.”

But when people say, “you can’t feed the world growing on a small family farm,” she steps in.

“One of my friends is a small farmer [and] challenged that notion… He said, ‘We’ve been doing it. Except for the last 70 years, people have been feeding themselves this way for tens of thousands of years.’ Although it’s only recently that community agriculture has picked up the way it has in central Illinois, people have grown this way forever.” iBi