In 1965, Peoria lost a historic landmark when its county courthouse was razed, but a treasure within the building was saved…and it’s heading back downtown this fall.

Built in 1873 and modeled after Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, the classically designed Peoria County Courthouse stood for nearly a century, housing an iconic clock within its dome. Weighing more than 1,000 pounds, the clock became a fixture of Peoria’s bustling downtown after its installation in the courthouse in 1878.

The clock and its bell were built by the Seth Thomas Clock Company of New York for about $3,000—$68,000 in today’s terms—minus the cost of labor. It was the handiwork of Andrew S. Hotchkiss, a world-renowned designer of tower clocks, who was known for high-quality craftsmanship. Each of its faces was about six-and-a-half feet in diameter, with numbers fashioned out of cast bronze. The bell could be heard tolling the hours for miles around the city, although locals complained that it never quite kept the right time.  Putting the Brakes on Demolition

Putting the Brakes on Demolition

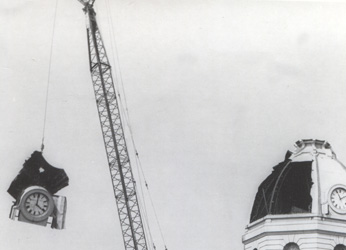

In 1964, the clock was nearly silenced forever. At that time, 19th-century buildings in cities across the country were falling victim to progress. With the construction of the new Peoria County Courthouse, the old limestone building—and the clock within it—were slated for demolition. The 6,000-pound bell was placed on display in the Courthouse Plaza, but little interest was shown in saving the clock itself…until Foster Vachon, a local businessman, stepped in.

Born in West Virginia, Vachon moved to Peoria in 1926 and founded Vachon Brake Service a decade later. When he first moved to town, he could see the courthouse clock from the window of his boarding house. “I used to look right down on the clock,” he said, “and I could listen to it strike all night through my open windows.”

Vachon bought the clock from the demolition company, and with the help of his brothers, John and Leonard, moved it to his business at 1409 SW Jefferson Street. The move was not an easy one. When the 14-foot, 500-pound pendulum was detached from the clock’s workings, it fell through several floors of the old courthouse. Thankfully, no one was injured, but one of the clock’s faces was damaged during the transition and had to be discarded.

After Vachon and his brothers cleaned and restored the clock, the remaining three faces were placed on the roof of Vachon Brake Service and the inner workings in the front window of the shop directly beneath. From then on, the clock served as an emblem for the business and the surrounding neighborhood.

Clock Switches Hands

Clock Switches Hands

A few years after the 1983 death of Foster Vachon, his family sold Vachon Brake Service, but not the clock. Beginning in 1988, a number of museums and businesses showed interest in the clock, and in1992, it was given to the Greater Peoria Airport Authority, with the idea of installing the clock near the airport’s main terminal.

Several years passed, and it became clear that the airport was unable to display the historic timepiece. In 1996, it was donated to the Peoria Historical Society, and almost immediately, it was loaned to Wheels O’ Time Museum. At this point, the clock underwent another restoration, this time led by John Parks, Sr. and Kent Brown. Part of the restoration included the attachment of a shorter pendulum so the clock could fit into the museum. When it was complete, it was put on display at Wheels O’ Time, where it remained for nearly 15 years.

Heart of the City

This October, when the Peoria Riverfront Museum opens its doors, the famous courthouse clock will make for a striking presence in the main stairwell. With this exciting new development, countless people will have the opportunity to see a significant piece of Peoria’s history up close.

The clock is once again being restored by John Parks, Sr., with the help of his son, John Parks, Jr., a museum board member. Using a timer and a series of microswitches, the father-son team is working on a motorized winding mechanism so museum staff does not have to physically wind the clock three times a day, as was previously necessary.

As early as 1996, the Peoria Riverfront Development Project, as it was then called, expressed interest in the clock. Throughout the planning stages, John Parks, Jr. pushed for the clock to become part of the new museum. While the museum is based on the Delta concept, meaning that it is always changing, “We felt it was an icon of the area and should be on permanent display,” he said. Both father and son have generously volunteered their time and equipment to ensure that the clock is in top condition for its return to downtown Peoria.

Nearly half a century since its removal from the courthouse, the old clock will once again tell time in the heart of the city. While the 1873 courthouse no longer stands, we can thank Foster Vachon and his family, the Peoria Historical Society, Wheels O’ Time Museum, the Parks family and many others for preserving a piece of it so that future generations can recognize its value. “I think there’s much more appreciation for our history now,” said John Parks, Jr. With the opening of the new museum, there will certainly be greater opportunities to experience that history up close. iBi

Meredith Tuttle is a history major at Eureka College and former intern at the Peoria Historical Society.

Sixty-Year Homecoming

Sixty-Year Homecoming

John Parks, Sr. is intimately familiar with Peoria’s famous courthouse clock, having restored it once before, prior to its installation at Wheels O’ Time Museum, which he co-founded in the late ‘70s. A former Caterpillar engineer and antique car buff, Parks has had a passion for “anything mechanical” for as long as he can remember. When he was just three or four years old, he snuck into his parents’ bedroom in order to take apart his mother’s watch and find out what was inside.

“It was a sunny day, and the south window had a nice window sill,” he recalled. “I set the watch on the window sill and got a paring knife from downstairs, and I took that watch apart and had all those little gears spread out…Then, I heard Mom coming up the stairs…Holy cow, I’m in deep trouble! So I moved the screen and shoved the whole mess outside. It fell down two floors into a bunch of bushes…She found out what I was doing and said, ‘Well, we better go down and see if we can find all those little gears.’ We tried, but of course, we couldn’t. They were so tiny, mixed up in the dirt…they were gone.

“She never bawled me out about that. When I wanted to do something mechanical, she was always behind me,” he explained. “About 60 years later, working at Caterpillar, I happened to run into an outfit that had spare [watch] works, and I found the works that would fit her watch. So I put it back in the case—and it worked. And I gave it back to her.”