The Guardian Angel Home has served children in need for nearly two centuries.

The Guardian Angel Residential Program for Youth, in its current iteration, is a residential treatment facility for boys located on Queenwood Road in Morton, Illinois. But “the Home,” as it’s often referred to, has actually been a part of central Illinois for nearly two centuries. A model for best practices in 21st-century residential treatment programming, it relies on the latest research in neurology and trauma, and prioritizes a relational approach to working with the boys, who have suffered physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect.

Its residents often come to the program from truly horrific, traumatic circumstances. Duane McKillip, clinical director at the Home, summarizes its message to them: “Your past can stay in the past, you are stronger than what happened to you, and you don’t have to work through it alone to reach a brighter future.”

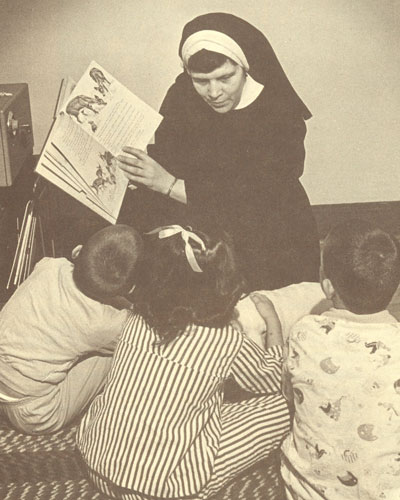

In 1932, the Heading Avenue Sisters organized the first Diocesan Orphan’s Day for the children of the Guardian Angel Home.

A Progression Over Time

The Guardian Angel Home can trace its origins all the way back to 1848, when it was originally established as a children’s orphanage in Metamora. When it needed to expand, the Home moved to a campus in West Peoria in 1914, and for nearly a century, it existed as part of Catholic Charities, run by the Catholic Diocese of Peoria. Coordinator James Kleine, who has been with the Guardian Angel Home since 1985, estimates that it housed around 300 kids during the Great Depression.

In the 1970s—in the wake of advances in social services and psychology—the “orphanage” model was phased out, and in its place, the model for a residential treatment center was established. At this point, the program began to work with the Illinois Department of Children & Family Services to refer kids who had been neglected or abused. State funding allowed the Guardian Angel Home to serve around 1,400 children in foster care and 50 children in the residential campus. Eventually, the state no longer needed as many beds for girls in residence, and in the late ‘90s, the focus of the program was changed to boys only.

In 2012, the Center for Youth and Family Solutions spun off the Catholic Diocese in order to continue the work of the Guardian Angel Home. Though it had beds for 16 boys, the West Peoria campus was over a century old; it was aging and had an institutional feel. So in 2016, the Home moved to a new location across the river in Morton.

Customized Treatment and Group Living

The program serves all of central and southern Illinois—and while this might seem like a large area, it’s important to understand that a residential treatment program is actually a last resort in terms of social services. “We are at the far end of the child welfare spectrum,” Kleine states. The boys who are referred to Guardian Angel have exhausted other home and foster care options, and have behavioral issues that require professional treatment.

When the Zeller Mental Health Center in Peoria closed some years ago, regional mental health centers for youth lost residential facilities. In many ways, the Guardian Angel Home has filled this gap, essentially offering the mental healthcare needed by boys who have suffered from abuse or neglect. It provides a group living experience, known as “milieu,” for residents, as well as a customized treatment plan that addresses each child’s specific emotional, behavioral, mental health and trauma recovery issues.

When the Zeller Mental Health Center in Peoria closed some years ago, regional mental health centers for youth lost residential facilities. In many ways, the Guardian Angel Home has filled this gap, essentially offering the mental healthcare needed by boys who have suffered from abuse or neglect. It provides a group living experience, known as “milieu,” for residents, as well as a customized treatment plan that addresses each child’s specific emotional, behavioral, mental health and trauma recovery issues.

There are two units in the program, with kids divided by age. The average resident is between eight and 15 years old, and the length of stay averages about a year—prolonged stays are not part of the philosophy. “The goal for us is to put these kids back into the community, and [have them] stay in the community,” Kleine notes. In fact, the program provides up to 90 days of aftercare, which includes connecting kids to therapy and treatment where they will be living, in order to help reintegrate them to their community.

A large part of the care provided at the Guardian Angel Home comes from a huge investment in its staff, who essentially live and work with the boys. They are trauma-trained, which is a necessity. Seventy-two hours of staff training are required, with an emphasis on the latest research in the field. Duane McKillip, who started working with residential programs in 1982, notes that “there have been huge changes in the work we do,” as the field has developed and been professionalized.

“All of the breakthroughs in the field of brain science… in the last several years have totally transformed the way we go about our work,” he adds. “Understanding the impact of trauma on the developing brain, and the development of techniques to begin to mend some of that damage, has been truly transformative in understanding and serving youth in residential treatment programs.”

Looking Out for One Another

By remodeling and attaching an addition to an old church in Morton, the program has been able to create a living facility that reflects the program’s overall philosophy. The “institutional” feel is gone, replaced by “a noticeably more home-like feel than it was before, or that is typical of other residential programs around the state,” McKillip explains.

The living quarters were specifically designed to be in a large “U” shape, allowing for careful monitoring and improved safety. The boys have single bedrooms, and each unit has two bathrooms. In addition, there are large, open, central living spaces—divided into different stations, such as homework and games—that allow for small group interactions among the kids, which helps with socialization.

The living quarters were specifically designed to be in a large “U” shape, allowing for careful monitoring and improved safety. The boys have single bedrooms, and each unit has two bathrooms. In addition, there are large, open, central living spaces—divided into different stations, such as homework and games—that allow for small group interactions among the kids, which helps with socialization.

There is a school on-site, tied to the Morton School District, which staffs it and provides not only curriculum, but technical equipment like iPads and smartboards. There is even a physical education teacher who comes to work with the boys in the gym. This has been a tremendous advantage of the relocation, according to Kleine, who has been “very, very gratified” by the Morton community’s response to the program moving into town. McKillip agrees, describing them as “unbelievably supportive.”

“Community members, churches, businesses, social groups like the 4-H, and service groups have all reached out and offered to help in ways I never expected,” he adds. “One day, a woman in her eighties stopped in and said, ‘I just wanted to check in to make sure my community is treating you right.’ It is refreshing to know that there is a place where looking out for others still matters.”

Looking out for one another is certainly a cornerstone of the program’s relational approach. Connections and relationships among residents and staff have always characterized the Guardian Angel Home, especially considering its long and storied history. In 2009, iBi published an article about the Home—which was read by many former residents and staff members, who were looking to reconnect with one another. (Check out the many comments from former residents and staff at peoriamagazines.com/ibi/2009/aug/peorias-guardian-angel-home.)

There is “a feeling of pride,” Klein adds, when former residents return for a visit. It feels good to hear them tell their families that “this was the best place I was at.” Some former residents even volunteer at the home, helping to teach skills to the boys. It’s a special relationship that allows men who have been through the program to serve as models for successful reintegration into the community, offering advice and guidance from a relatable perspective.

Rev. Ed Farrell, Guardian Angel chaplain, with 1934 football team

Helping the Vulnerable

A famous quote, attributed to Ghandi, states: “The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.” As a community, it is our responsibility to come together and lift up those who are vulnerable. The boys served by the Guardian Angel Home have a broken relationship with community—and healing this relationship is the ultimate goal of the residential program.

Providing a place of safe refuge and sanctuary is of the immediate, utmost importance when boys first come to the Home. The staff, with the help of doctors, therapists, teachers and others, give them that safe space. But as a community, we also have a part to play in making the place we live a supportive, caring refuge for kids whose life circumstances have put them in vulnerable situations.

Our support, whether by volunteering our time and energy, providing donations, or offering words of encouragement, matters. By supporting their tireless work, we can help these kids see that they don’t have to “work through it alone” in order to be a bright part of our community’s future. iBi

There are opportunities for volunteers at the Guardian Angel Home. Interested persons, who must have a thorough background check, can explore these possibilities by contacting Sue Hirschman at (309) 323-6600 or [email protected].