How the “Complete Streets” model creates mobility options for all and invites regional discussion

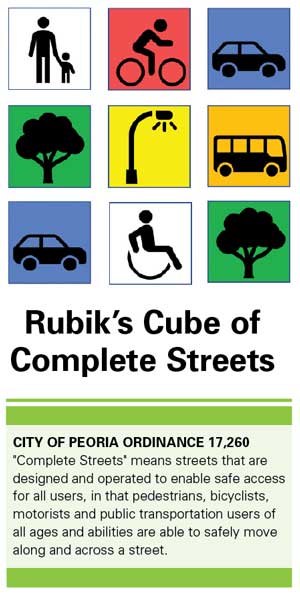

Think of a street like a Rubik’s cube. Different colored squares could represent modes of transportation or streetscape elements. A side made of all blue squares would signify a car-only street. However, adding other colors would incorporate sidewalks, bus stops, trees, bike lanes and light fixtures. The end product is a multicolored cube, showing several transportation options in a safe space—i.e., the concept of a “Complete Street.”

This type of holistic design mentality will be the emphasis of a regionally-focused symposium in Peoria on May 10, 2018. Until then, however, it is important to understand how Complete Streets can affect quality of life, shape policy and legislation, and even influence the regional economy.

Complete Streets Concepts

Complete Streets Concepts

The Complete Streets model describes carefully designed streetscapes that include safer spaces for all users and more transportation options than just cars. But it varies considerably depending on the context. “[The Complete Streets concept] is not a one-size-fits-all,” said Nick Stoffer, traffic engineer for the City of Peoria. “I don’t think there’s one right answer.”

When it comes to redesigning a streetscape, each community’s goals are unique and likely not exclusive to transportation. “Our infrastructure needs to do more than one thing. It can’t just be for transportation of automobiles,” explains Anthony Corso, chief innovation officer for Peoria’s Innovation Team. He notes that transportation infrastructure can shift people’s perceptions of an area. “When you actually have a strong connection to a physical place, that changes your behavior. You’re more likely to invest in it. Things tend to be a little more sustainable in the long term because people see value in something.”

While Complete Streets are designed to accommodate people of differing ages and abilities, certain types of users may benefit more than others. As Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) representatives Holly Ostdick, bureau chief of planning, and Christopher Maushard, project engineer, have outlined in a statement: “Demographic changes also indicate that as generations age, Complete Streets will be a necessity for moving around. It’s been documented that millennials prefer Complete Streets and as the population ages, elderly are more likely to live in walkable communities to retain their mobility.” In fact, in 2013, AARP published a Complete Streets implementation case study outlining transportation design strategies that would have the most impact on an aging population.

Strategic elements such as better street lighting or added walking and biking paths can encourage more people to use the space—perhaps even those who might have felt uncomfortable doing so before. “More eyes on the street and more vibrancy leads to safer areas,” Stoffer explains.

As a result, in these “Completed” streets, users will likely spend more time and money at local businesses. “For most North American cities, our main public space is our streetscapes … not only connectors of places, but connectors of people,” Corso says. “If you design those as a pleasant, safe, accommodating place for all users, you are going to have more feet on the street, more activity; you're going to create a nicer space for people to connect, and a direct result, you're going to have more economic vitality.”

Finally, further than the human impact, Complete Streets can be designed with an eye to the environment. “We have a philosophy here in Peoria called Complete Green Streets,” explains Scott Reeise, the City’s director of public works. “By reducing the pavement that’s out there, there’s less runoff, so less water gets into your storm sewer.” Impermeable pavement reduction strategies include the creation of rain gardens and bioswales, he adds, which allow for natural infiltration to occur instead of accumulating water in underground pipes. This is one way Peoria has been tackling its Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) issue. By breaking up the concrete atmosphere, this streetside greenery can also potentially reduce ground-level ozone and improve air quality.

Policies, Plans and Payments

In late 2015, the Peoria City Council passed Ordinance 17,260, commonly known as the Complete Streets ordinance. It ruled that “the City shall approach every transportation improvement and project phase as an opportunity to create safer, more accessible streets for all users.” It also stated that Complete Streets principles will be integrated in other aspects of the city, such as plans and documents encompassing transportation design.

Both the Illinois and U.S. Departments of Transportation have Complete Streets concepts on their radar. IDOT’s Ostdick and Maushard mention that “Illinois has Complete Streets legislation which requires that when improvements are made, all modes be considered a user of that facility.”

Betsy Tracy, transportation planning specialist of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Illinois Division, explains that when it comes to transportation infrastructure changes, the federal government greatly emphasizes safety. That means Complete Streets elements such as clearer signage or decreased vehicle speeds could tie into FHWA’s performance measures, which highlight the reduction of injuries and fatalities. These performance measures, which are required to be tracked on a regional level, focus on both motorized and non-motorized transportation.

Additionally, Tri-County Regional Planning Commission, which produces periodically updated documents such as the Transportation Improvement Program and the Long-Range Transportation Plan, also must address how federally-funded projects, which could include Complete Streets measures, will benefit regional safety.

Of course, as is the case for both IDOT and FHWA, “Everybody’s vying for a limited amount of funding,” Tracy says. “So it’s often about finding the money to be able to do a project.” When there are other transportation developments throughout the region, let alone statewide or nationwide, the difficulty comes in allocating money to those considered highest priority.

Ripples throughout the Region

One way to plan for these Complete Streets practices is to propel a regionally-focused conversation. “We want to collaborate as a region—and we need to,” Corso says. “Otherwise, we're not going to survive as a region.” In the tri-county area of Peoria, Woodford and Tazewell counties, Downtown Peoria is the urban core, which should be carefully considered. This does not mean ignoring surrounding communities; rather, striving toward a healthy core will result in more palpable ripple effects in nearby areas. “As Downtown Peoria goes, the entire region goes,” Reeise notes.

But before it gets that far, it is important to recognize the progress that has already been made. Reeise mentions the Warehouse District, for example, with street improvements along Adams, Jefferson and Washington streets that have “rejuvenated” the downtown area. “Main and University is also a good example of the positives and negatives of Complete Streets,” Stoffer adds. “That’s an intersection [where] you really get the butting of heads between the pedestrians and the cars. Because we did limit the car access, but we vastly improved the pedestrian safety and access in that location.” Other projects involving Forrest Hill and MacArthur Highway contained Complete Streets elements, including lighting and bike accommodations.

Another such project outside of Peoria was in the City of Elmwood, which received $1.7 million from the Illinois Transportation Enhancement Program (ITEP) to restructure its downtown streetscape in 2013. Improvements compliant with the American Disabilities Act (ADA), as well as streetside plants, were installed. While there is more to be done, these projects serve as an encouraging start.

Above all, city and regional officials agree that when it comes to Complete Streets discussions, it is particularly valuable to educate and involve the public. “That’s kind of our social responsibility,” Stoffer affirms. iBi