By enhancing natural fibers with the properties of synthetics, Natural Fiber Welding could revolutionize multiple industries while providing great social and environmental benefits.

The humble office at Natural Fiber Welding’s industrial space on Peoria’s north side is the perfect façade to founder Dr. Luke Haverhals’ and COO Steve Zika’s combined energy. Quiet and unassuming at first, the office fronts a bustling campus of specialized equipment and colossal scientific endeavors. Haverhals and Zika are that rare breed of “systems people”—those who can wax prophetic on issues like humans’ environmental impact on Earth, the audacity of Rube Goldberg machines to perform simple tasks, and the ethics of corporate greed—linking seemingly disparate topics in a natural tune only virtuosos can carry.

Hearing them talk about the Peoria-based startup, it’s easy to understand the confidence with which they believe their technology can disrupt entire industries.

Working with Nature

The discovery came to Haverhals as an assistant research professor conducting fundamental research for the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. He was focusing on the development of novel ionic liquid-based processing of biomaterials—think liquid wood—and how natural fibers like silk could be blended with other natural fibers into liquid forms for easier processing. His “aha moment” came one day while trying to make a solution of industrial hemp.

“Every time I tried to make a solution, the fibers would literally ‘weld’ together, and you couldn’t undo it,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Hmm, am I working too hard here? If I can just get fiber to do that, then why spend all this extra solvent to fully dissolve it?’”

In short, Haverhals discovered that when natural fibers are blended with an appropriate ionic fluid, it enables them to fuse with different, neighboring fibers. Meanwhile, the polymers in the fiber core are left in their native states. By manipulating natural materials in ways analogous to the manipulation of plastics from petroleum, Haverhals was able to create a better version of the natural material.

In short, Haverhals discovered that when natural fibers are blended with an appropriate ionic fluid, it enables them to fuse with different, neighboring fibers. Meanwhile, the polymers in the fiber core are left in their native states. By manipulating natural materials in ways analogous to the manipulation of plastics from petroleum, Haverhals was able to create a better version of the natural material.

Of course, the benefits of synthetic fibers like polyester lie in their strength, durability, elasticity, waterproofing, stain resistance… and the list goes on. “But people don’t actually prefer polyester—especially the way it tends to hold onto odors,” Haverhals notes. “People, unknowingly, prefer the manufactured format of polyester.”

What you actually like when you select your quick-dry, durable, lightweight yoga pants, for instance, is not that they’re polyester fabric, but that polyester can be a filament fiber, he points out. “Geometry and the laws of physics are dictating many of those attributes, not necessarily the laws of chemistry regarding the base polymer.”

“Nature already has this all figured out,” he continues. “When nature grows polymers of various sorts, they’re wondrously put together. The polymers are literally manufactured at the nano-level up. So they have very unique properties because of that order and structure at all scales of the material. We were finding that when you fully dissolve things, you have a hard time of making things ‘better.’”

Like an egg that can never regain its structure once cracked, fully dissolved natural materials will forever lack the perfect structure nature gave them. But if you take two fibers and add this chemistry, Haverhals says, the fibers get swollen, so they interact in a new way at the molecular level. You can then “wash out” that chemistry, recycle it for reuse, and the fibers congeal in a new, yet still natural way. The result? Sustainable, high-performance, bio-based composite materials that are a viable alternative to petroleum-based plastics—with applications in the textile industry and beyond.

“What you couldn’t do before was take something like cotton—a staple fiber—and turn it into something that performs like a filament. But now you can,” Haverhals adds. “So we’re just combining the cotton that you like for its reasons of chemistry, into the format that’s only ever been convenient to make before from synthetic polymers—so you get the best of both worlds.”

Fit and Fate

For two years, Dr. Haverhals worked to document the science behind his serendipitous discovery. In the meantime, he and his wife had three little girls and landed back in the Midwest to be closer to family. Accepting a job at Bradley University as a professor of chemistry, he began working with the USDA Ag Lab to further his research.

“We had been doing fairly simple experiments at the Naval Academy, working with cellulose, silk, wool or very specific materials,” he explains. “But working with the Ag Lab opened our scope to a whole lot of different kinds of fibers and materials—and thinking about how to scale the process.” For instance, what could be done with excess agave fiber in the tequila-making process? Or what if there was a local market for farmers to grow industrial hemp or flax, instead of corn and soybeans? By the summer of 2015, the concept for Natural Fiber Welding (NFW) was fleshed out.

Steve Zika, co-founder of social investment firm Attollo, met Haverhals through Bradley’s Turner Center for Entrepreneurship during a practice investment pitch in January 2016. For Zika—who holds multiple degrees in materials science engineering from Stanford University and serves as executive director of KidKnits, a nonprofit social business specializing in the distribution of fair-trade, imported, hand-spun yarn—NFW was a natural fit. “I just found the concept to be so incredibly interesting,” he explains. “It’s a materials project, which is my technical background, and it had to do with yarn [like KidKnits], so there were all these connection points.”

The two talked more after the initial pitch, and soon Attollo became NFW’s first investor. Zika began spending more time mentoring and advising Haverhals; by the summer of 2016, he had joined the project full-time as chief operating officer.

The two talked more after the initial pitch, and soon Attollo became NFW’s first investor. Zika began spending more time mentoring and advising Haverhals; by the summer of 2016, he had joined the project full-time as chief operating officer.

Haverhals considers himself fortunate. “I happened to have a paying job that directly interfaced me with [the right] people in Peoria. If you’re an entrepreneur in Peoria, and you’re fortunate enough to meet Chad Stamper and Steve Zika, then it’s probably true that you’re going to be well taken care of,” he says with a chuckle. As director of technology commercialization at the Illinois Small Business Development Center at Bradley, Stamper helped Haverhals work though intellectual property issues; he now serves as commercialization manager for NFW.

Remaking the System

What NFW is doing—enhancing natural fibers for better performance—sounds simple, but the applications are vast. Improved fibers have the potential to not only revolutionize the textile world, but could improve packaging material and the composition of various products—like the box your Amazon order just arrived in, the pallet on which it was shipped, or the actual product itself—via a brand-new way of manufacturing.

As such, Haverhals calls NFW a disruptive chemistry and technology company, because through the use of their technology, every part of the current system and way of doing things could change.

“‘Disruptive’ is a term that has lost its meaning,” suggests Haverhals. “The true sense of the word is to completely reinvent how industry is done.” For instance, computers were disruptive, and when computers got small enough, cell phones became disruptive, and now there’s Netflix, which is disrupting the distribution of media, he offers. But the company is careful in its messaging not to be too disruptive.

“To begin with, there’s a compatibility that’s really important because you’re not going to convince people to throw away all the equipment they have,” Zika explains. “Easier market entry is [offering] a brand-new material with properties that have never existed before, but which you can fit into the existing supply chain”—like winding new materials onto standardized spools that are the correct size and format to process using existing equipment.

In time, NFW would like to be the primary driver behind a materials manufacturing, distribution and upcycling revolution that not only changes the way the system operates, but shifts the socioeconomic status of people around the world.

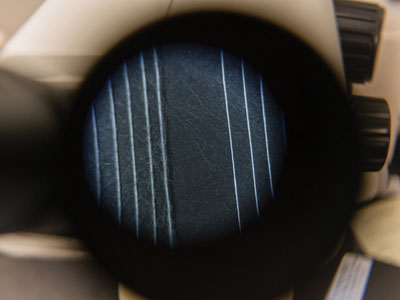

Natural Fiber Weldinghas worked to improve its yarn winding machinery to ensure its textiles meet the industry standard.

Cradle to Cradle

The goals of Natural Fiber Welding span further than meets the eye. “At this point in human history, we process and consume a cubic mile of petroleum per year,” Haverhals begins. “That’s a gargantuan volume, but that cubic mile of petroleum really only gets utilized by 20 percent of the Earth’s population… Another four out of five go about their lives living what we would call ‘poor,’ because they don’t have access to that limited resource.

“Meanwhile, more new plant matter grows in a day on the planet than the tonnage of all the synthetic chemistries touched by mankind in a year,” he adds. “The earth is abundant.”

Raised on a farm where his father and grandfather grew corn and soybeans year after year, Haverhals understands the value of the land. When farmers use their highly productive acres to grow fuel, he calls it “an exercise in racing to the bottom.” But when they can take their highly productive acres to produce highly abundant natural materials—which people will also pay a lot more for—it’s “an exercise in adding value.”

“There’s this concept of ‘cradle to cradle’ that people are using,” he adds. “The idea is that you form closed loops in how you use your materials. But nature’s already solved the problem. Nature is the original ‘cradle to cradle.’ “There’s just a very rich opportunity to take natural materials that grow in abundance that are high-performance, and now, with fiber welding… a very facile way to manufacture many kinds of products—not everything—but enough that would enable higher standards of living for all people on the planet… not just one in five.”

Directionally Correct

“Peoria’s entrepreneurial ecosystem is bubbling with all sorts of things,” says Zika, rattling off the benefits of NFW’s Midwestern location, including ease of shipping and transportation, low overhead and exceptional talent. (The company has now happily hired five former Caterpillar engineers.) “One of our core values is that we’re grateful to be from where we’re from.”

“It’s easy to get lost in a bunch of engineering principles and automation and chemistry details,” Haverhals notes. “But set that all aside, and look at what this is—the ability to take local, abundant resources and add value and make things that enable a higher standard of living in a way that doesn’t require the amount of resources that we currently consume. It’s an opportunity to have a very positive social benefit.

“It’s easy to get lost in a bunch of engineering principles and automation and chemistry details,” Haverhals notes. “But set that all aside, and look at what this is—the ability to take local, abundant resources and add value and make things that enable a higher standard of living in a way that doesn’t require the amount of resources that we currently consume. It’s an opportunity to have a very positive social benefit.

“Fiber welding isn’t going to solve all these problems,” he adds, “but any time that you can reduce resource competition and demand, it’s directionally correct.” For now, NFW is starting simple. The company’s north Peoria campus is working to create machinery that adds the chemistry to the fiber combination processes, washes it off, and recycles it in a continuous loop.

“There are some very straightforward things we can do in the textile world,” Haverhals says, “and there are some very straightforward things we think we can do with building products of various sorts over time.”

As it enters the new year, the company will focus on securing the next round of funding and continuing to build its technical team, which now numbers 15 employees. As a startup, they are moving very methodically through a timeline of milestones. Through extensive research, they have confirmed that customers are looking for particular attributes in their clothing—and that they care about their textiles being natural and sustainable. It’s a huge market opportunity.

“Built into the DNA of the company is a whole bunch of people that believe in the core idea of building a technology that’s for the benefit of people [and] truly benefits humanity in a positive way,” Haverhals adds. “We’re not using fiber welding to take us to the moon at this point,” he says with a laugh, but the look in his eyes suggests the idea is not so far-fetched. iBi

For more information, visit naturalfiberwelding.com.