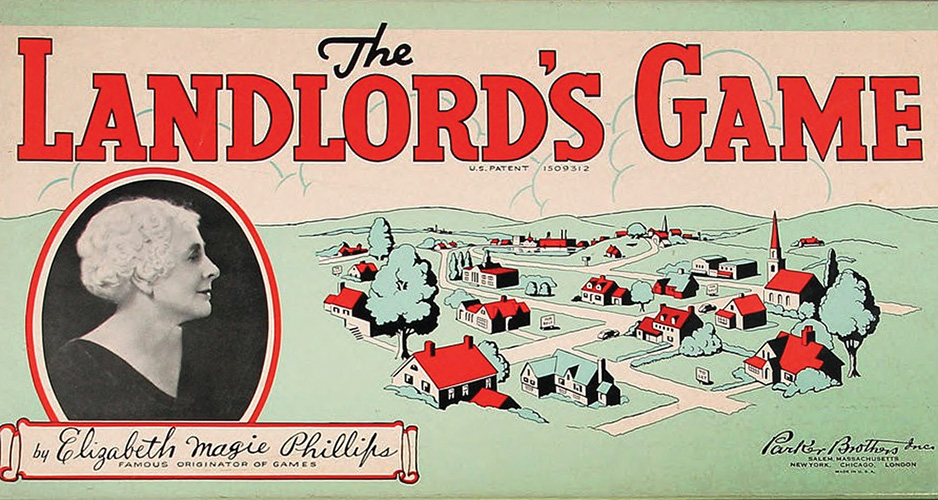

Monopoly inventor Lizzie Magie of Macomb never did, even as her board game became America’s most popular

Chances are you have crossed Boardwalk and collected $200 a time or two in your life. If you’ve ever played Monopoly, America’s most popular board game, you know the drill.

Since its introduction in 1935, more than 250 million Monopoly sets have been sold across 114 countries, while being translated into 47 languages.

You know the game, but you don’t know the story behind Monopoly.

In 1866, Lizzie J. Magie was born in rural Macomb. At a time when women had very few options for careers, Lizzie didn’t let anything hold her back.

Her father, James K. Magie, was the town’s postmaster and owner of the Macomb Journal newspaper. As a result, the big ideas to which she was exposed growing up made Lizzie “a very independent woman,” said Jock Hedblade, executive director of the Macomb Convention and Visitors Bureau.

While living in Chicago in 1906, Lizzie placed a tongue-in-cheek ad in the newspaper offering her services as a “young woman American slave,” which was her way of trying to bring attention to the poor working conditions and low wages suffered by unmarried women in America, recalled Hedblade. “To her dismay, many sent her offers,” he said. More importantly, the ad became something of a rallying cry for American feminists.

In the early 1900s, when the nation’s capitalist economic system was not well regulated, the scales were tipped in favor of a wealthy minority, while most Americans barely scraped by. Lizzie saw and resented these class differences. She became a follower of Henry George, who had authored a popular book, Progress and Poverty, that preached against capitalism’s excesses. His followers, called Georgists, were critical of monopolies and the business titans whose practices made them possible.

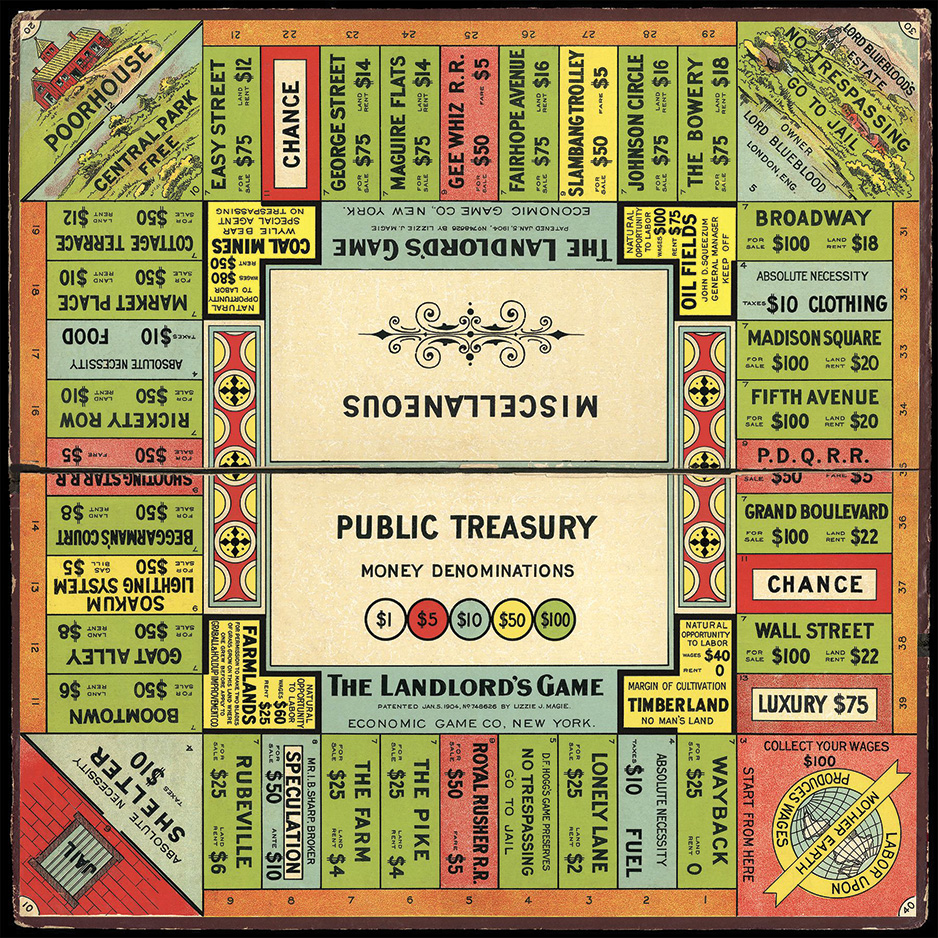

That book and the movement it spawned inspired Lizzie to create The Landlord’s Game in order to expose the injustices produced by those monopolies.

“When that didn’t work out as planned, she revamped the game so you could play it two ways,” said Hedblade. “One way was as a monopolist and the other as an anti-monopolist, where rent profits go into the public treasury for railroads and public utilities.” In 1904, Magie applied for a patent on The Landlord’s Game.

The original game bears striking similarities to the city of Macomb. At one time, Macomb’s square had a poor house, a public park and a jail on the corner. On the board game since the very beginning were three little words: “Go to jail.”

Magie’s patent meant she got credit for the board game’s creation, if not the profits from its sale. So, how did the Monopoly game find its way into American homes?

Back then, board games were expensive to purchase. As a result, people would create their own game boards on paper or oilcloth. As a result, over the years the game morphed into slightly different layouts, with the rules evolving, as well. Ultimately, The Landlord’s Game landed with a Quaker teacher in Atlantic City. Baltic Avenue, Park Place and other Atlantic City landmarks made their way onto the board.

Enter a man named Charles Darrow, who played one of these homespun versions of the game, spruced it up, and sought a patent in 1935 for the newly named Monopoly game. Darrow then sold it to Parker Brothers, the biggest game distributor in the nation.

Of course, Parker Brothers wanted to ensure that Darrow really was the game’s inventor. In researching its origins as part of their due diligence, they discovered Magie’s patent for The Landlord’s Game, which was remarkably similar to Monopoly.

Soon thereafter, company founder George Parker met with Magie and sweet-talked her into signing over the rights to the game for a meager $500 and a promise to publish two more of her original games.

Lizzie Magie drew a Chance card and rolled the dice, but she didn’t pass go and didn’t collect $200 because she wanted her Georgist antimonopoly teachings to reach a broader audience. Little did she know that her game would become more of a lesson in greed, instead.

To learn more about Lizzie’s story, watch the WTVP story Ruthless: Monopoly’s Secret History and WTVP’s You Gotta See This! episode on Magie.