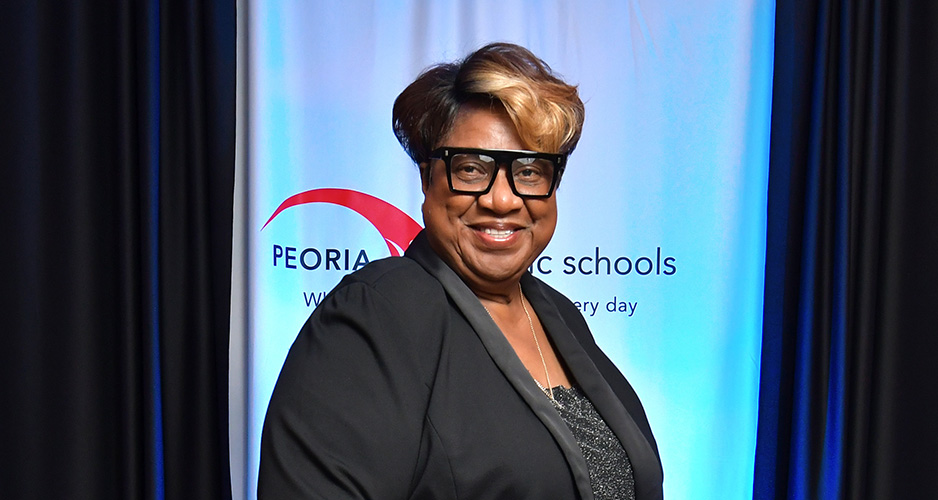

Martha Ross has come a long way in her life, and is committed to helping young Peorians do the same.

Martha Ross has always been surrounded by children.

She grew up in a three-room house with eight siblings, two grandmothers, and her mother and father. Ross recalls a happy childhood: “When you grow up in cramped quarters like that, you’re close.”

She went on to have three daughters of her own — Wondra, Alzebett and Sidney – and now brags nine grandchildren and 13 great-grandchildren, two of which she has raised since soon after they were born. They are 14 and 16 years old now.

Today, Ross has expanded her efforts on behalf of children to the community at large, as president of the Board of Education for Peoria Public Schools, with more than 12,800 students in its charge. It is a position she pursued because “it’s all about the children.”

A hardscrabble beginning

Born Martha Chew and raised in Byhalia, Mississippi, Ross worked in the fields with her sharecropper family.

Sharecropping began after the Civil War, when the usually white landlord allowed a tenant, often a Black person, to farm and often live on the land in exchange for a percentage of the crop. Before getting their share, however, sharecroppers had to pay for the farming and living expenses accrued during the previous year.

As Ross recalled, “my dad was always told he didn’t break even,” which was often the case, keeping sharecroppers indebted year after year to the landowner or merchants who advanced them credit.

The Chew family farmed 40 acres of cotton and 40 acres of corn. Ross recalled the three-room house where she grew up as “really primitive.

“There were no inside bathrooms or running water,” she said. “Right after I was born, my mother put me in an orange crate at the end of the row.” Her brother, who was 3 years old at the time, was charged with looking after his baby sister.

Ross was 6 when her father decided it was time for her to start picking cotton. “I hated it so bad,” Ross said. “You had to carry around your neck the sack that you put the cotton in. Then you had to put your hand inside the cotton boll … and it’d make your hands bleed.”

A grandmother who lived to be 100 years old was the family’s best cotton picker. Meanwhile, Ross’s father kept an eye on how much cotton his daughter picked each day.

Ross attended an all-Black school because state laws excluded Black youngsters from attending the “white” schools. There was a railroad track in Byhalia “and we knew not to cross it,” said Ross. The water fountains and public restrooms in Mississippi were designated white or “colored.”

Opportunity awaits elsewhere

“When I was 19 … my granddad came to visit from Memphis, Tennessee,” said Ross. “I begged to go back to Memphis with him.”

Her father finally agreed to let her go, on the condition she get a job there. “I took the first job there was, as a maid at Holiday Inn,” she said. “Otherwise, I’d have to go back to the cotton field.”

Ross lived with her grandfather for five years while working one, sometimes two jobs and going to school. “I figured I’d get an education and not have to go back to Mississippi.” Her studies included two-year certification programs in the career areas of legal secretary, nurse assistant, architectural engineering, biomedical engineering and cosmetology.

Once Ross had her own apartment in Memphis, six of her eight siblings soon joined her. “My brothers and sisters were raring to get out of Mississippi, too,” she said.

Peoria beckons

Ross spent three and a half years studying early childhood education at Memphis State University, stopping short of a degree.

“From the time I left Mississippi, I had a passion for children and how to help kids succeed,” she said. But she knew from her own experience that the educational system for Black children wasn’t adequate. She was a product of Mississippi’s educational system with “A” grades “but in college it was a ‘D’ because the educational foundation was just not there.”

After living briefly in Washington, D.C. and California, Ross moved to Peoria on the recommendation of a friend who promised, “It’s better here.”

Within four months of arriving in central Illinois in 1980, Ross had jobs at Peoria’s Urban League and doing cosmetology. A customer at the latter introduced her to Sidney P. Ross. She married him that same year.

Over the years, Ross worked at Salvation Army, Carver Center and United Way. She finished up at Bradley University, receiving a bachelor’s degree in social services and a master’s degree in human development counseling.

On June 4, 2012, Ross was diagnosed with breast cancer. The next day, her husband of 32 years died, succumbing to heart failure.

“When I told him of my cancer diagnosis, he said, ‘I guess I better get better, so I can take care of you,’” she recalled. “Then the next day he was gone.”

Helping children ‘to see value in themselves’

At 21 years, Ross is the most senior member of the current Peoria Board of Education but not the longest serving ever, a distinction that belongs to Leo Sullivan (1963-1986).

Ross got her start on the School Board in 2001, when a seat came open and she was appointed to it. In 2003, she campaigned for the District 1 seat serving Peoria’s South Side, was elected to a full term and has been reelected ever since. She served as board president from 2015 to 2018, and again this past year.

She cites that institutional history as a big advantage. When new members want to make changes, “I can say, ‘We tried that and it didn’t work,’ not because I don’t want change, but so we can look at how to do it differently this time.”

In April, at the age of 75, Ross will run for another five-year term on the School Board. Should she win, it will be her last.

School Board members are unpaid. She serves because “I’m passionate about children and I’m passionate about families,” said Ross, whose devotion to the city’s South Side extends to her longtime presidency of the Goose Lake Neighborhood Association.

In her time on the board, Ross is most pleased to have had a hand in establishing Parent University, “helping parents help their children to see value in themselves,” she said.

‘It’s important we help these kids understand they didn’t come from slavery. They came from royalty.’— Martha Ross

“It’s important we help these kids understand they didn’t come from slavery. They came from royalty,” she said. “Somehow, I just feel if they have value in themselves and a future, some attitudes would change.” But, she admits, “Things haven’t changed a whole lot.”

Growing up in an era and a region where Black people were restricted from fulfilling their ambitions, Ross has backed efforts to get students the resources they need to work and live where they please.

She cites the PPS program D Squared, a two-year study program for high school juniors that, once completed, simultaneously earns them both a high school diploma and a degree from Illinois Central College. She is proud, as well, of the district’s vocational offerings. Meanwhile, during her tenure the district opened the Wraparound Center, which attends to students’ social emotional learning needs.

Her goal is for Peoria Public Schools to be a trend-setter for other districts.

“We have people from outside our district paying to send their kids here,” said Ross. “They want their kids to be here.”