Touting the proposed Peoria-to-Chicago rail line, Ray LaHood explained the cost.

“This is not an inexpensive project,” the former U.S. secretary of transportation said at a City Hall press conference in July. “We estimate the cost of this to be in the neighborhood of $2.5 billion. That’s ‘B’ — billion.”

His point: It’s an impressive number, but – right here, right now – a suddenly doable number. With the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allotting $66 billion for such projects, LaHood and likeminded proponents think the proposal has a real chance.

“2.5 billion is a lot of money,” he added later. “But that’s the kind of money that it will take in order to make this project happen, and maybe even some money in addition to that.”

Indeed. Maybe $1.5 billion more.

Mind you, his new assessment comes despite a 40% contingency fee built into the $2.5 billion estimate. But LaHood — who has discussed the proposal with officials running Amtrak and the Federal Railroad Administration — doesn’t see the markup as a problem.

Indeed, rail project overages aren’t unusual, said LaHood, who points to California’s high-speed rail project, now being constructed between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Its cost has risen from $33 billion in 2008 to $113 billion today, an increase of 242 percent.

Potentially, local and state funds might also become available for a rail project that also promises an economic boost, said Peoria Mayor Rita Ali, who believes a line could be up and running within a decade.

“But if we don’t start now, it won’t be 7 to 10 years,” she said. “It’ll be double that.”

For rail advocates, the wait already has been far too long.

The Rock Island Railroad ran Rocket passenger trains from Peoria to Chicago from 1937 to 1978, when deteriorating rail lines and ridership prompted a shutdown of that service. In 1980 and 1981, Amtrak and the state of Illinois ran the Prairie Marksman passenger train from Chicago to East Peoria, but poor ridership ended that effort. The bankrupt Rock Island Railroad ceased operations in 1980, though the Rocket line to Chicago has been kept alive by various freight interests.

In the decades since, there have been on-again, off-again calls to revive the River City to Windy City line, but official discussions went nowhere. The most significant progress came in 2011, when IDOT conducted a feasibility study of a commuter train line from East Peoria to Normal, where passengers could board Amtrak to Chicago. Ultimately, the study concluded that the effort would be cost prohibitive.

With that, the city of Peoria retained its dubious railroad-challenged distinction. Of the 15 biggest cities in Illinois, Peoria, at number eight, is the only one without current or planned access to passenger rail service (Rockford is in the design/construction phase). Further, the Peoria Metropolitan Area, with a population of just over 400,000, is the largest metro area in the state without train access.

But the $66 billion rail kitty has sparked renewed enthusiasm for a Peoria-to-Chicago line. Early this year, a city survey garnered an impressive 31,000 respondents, 83 percent of whom indicated they “very likely” would use the line.

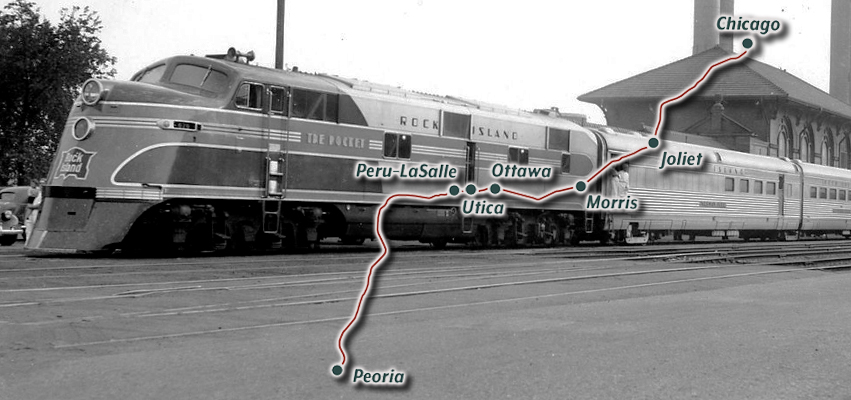

Other communities also have a horse in this race. The route, which would offer five, 2.5-hour trips a day each way, would include stops in LaSalle-Peru, Ottawa, Morris and Joliet, plus a flag stop in Utica, meaning a train would stop there if at least one passenger had purchased a ticket in advance. Of those communities, none aside from Joliet — which is on the Amtrak route connecting Chicago to St. Louis — has passenger service.

At the July press conference in Peoria, proponents touted a feasibility study offering fledgling insight into the proposed route, including the following:

- The route from Peoria to Joliet has 40 bridges, including a moveable lift bridge over the Des Plaines River in Joliet. There are 110 public at-grade crossings and 104 private at-grade crossings. Further, the tracks’ gradings ranged from Class I (15 mph maximum) to Class III (60 mph max). Improvements would be needed on the rail lines and crossings to allow 79-mph service, though in some areas 90 mph might be possible.

- New stations would have to be built at every stop south of Joliet (with just a platform needed for Utica). In Peoria, there are two possible station sites: the current location of the U.S. Post Office on State Street, or across from the Gateway Building on Water Street.

- A new layover facility in the Peoria area would be needed for the crew and the storage and service of equipment, with enough room to shuffle train cars in the event of last-minute issues.

But the $2.5 billion does not include all aspects of the proposal.

- The study did not contact owners of the existing rail lines along the proposed route. “It can be assumed that all of them would require additional capacity improvements to maintain their existing service and be able to efficiently handle the passenger traffic that would result,” the study stated.

- Amtrak, as the presumed operator, would incur additional costs, with additional demands on technology, crews and stations. According to the study, such costs would be carried by the state.

Another study is forthcoming from the North Central Illinois Council of Governments, thanks to $310,000 from IDOT.

Meanwhile, Ali says the city might help fund research into the application process involved in getting accepted into the Federal Railroad Administration’s new Corridor Identification and Development Program, which would move Peoria closer to its goal. Beyond that, the mayor does not anticipate much in additional city costs, though financial projections and shared obligations would be determined through further research.

The latter will include an analysis of potential ridership. The feasibility study pegged beginning daily ridership between 280 and 820, growing to between 320 and 860 by 2040. It’s unclear at this point whether those numbers would be acceptable to the Federal Railroad Administration.

The study also will show projected spinoff economic benefits for cities on the route. LaHood points to Normal, where the Amtrak station has helped revitalize that community’s Uptown area, adjacent to Illinois State University, with multiple developments including two hotels and a children’s museum.

“That’s what will happen along this corridor,” LaHood said. “That’s what will happen in Downtown Peoria.”

That might spark entrepreneurs to not only set up shop but also fund projects connected to the train station and rail line, Ali said.

Alas, LaHood cautions advocates to stay grounded. There are at least 15 other rail projects fighting for slices of the $66 billion, and Amtrak will want a chunk of its own. It’s good to dream big dreams, but success will come via research, preparation, and acceptance into the Corridor Identification and Development Program, which will select projects in part according to readiness to commence.

“We’re not on their radar,” LaHood said. “We need that designation. Then we’ll be on people’s radar.”