Just off Illinois Route 26 a few miles north of Spring Bay sits a soybean field, under which has lurked a secret for, well … for a millennia or so.

It’s commonly known as the Fandel property, and since the early 11th century, it has concealed clues just below its surface regarding the origins, rise and fall of the Mississippian Indian culture that once flourished in the incomparably fertile Illinois River valley.

Not only that, but it may hold hints behind the enduring mystery of what really happened at Cahokia Mounds, for three centuries starting in 1050 A.D. the cultural and population center of a political and religious transformation in the North American mid-continent – with more people than London at the time, not to be surpassed in what would become the United States for another four centuries.

“This whole region (of central Illinois), archeologically speaking, is just incredible,” Greg Wilson, Ph.D., professor of anthropology at the University of California Santa Barbara, said recently from the dig site.

An Illinois native – he hails from Marissa in St. Clair County, “in the shadow of Cahokia Mounds” – Wilson has long been fascinated by what transpired and why at the center of the Mississippian universe, at the largest and most complex manmade earthen mound and archeological site in the world outside of Mexico.

An Illinois native – he hails from Marissa in St. Clair County, “in the shadow of Cahokia Mounds” – Wilson has long been fascinated by what transpired and why at the center of the Mississippian universe, at the largest and most complex manmade earthen mound and archeological site in the world outside of Mexico.

In trying to answer those questions, Wilson’s program at UC Santa Barbara is partnering with Northern Illinois University, specifically with Dana Bardolph, Ph.D. — a former student of his — and her team there.

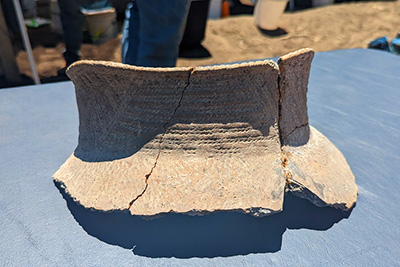

Remarkably, they’re finding evidence, in the pottery and other artifacts – gaming stones used to settle political disputes, Cahokia-style projectile points, etc. — unearthed at the site, that there was travel and direct trade between those two cultures, 175 miles apart as the crow flies.

“These were no ordinary buildings,” Wilson said of the five structure foundations they’ve excavated. “They’re temples.” Fundamentally, the scientists are trying to answer the question of what the relationship was between the early Mississippians and what was happening in Cahokia.

At this point, it seems that for a few hundred years – before everything went south in the 14th century – there were peaceful interactions between these Native Americans, based around their religious practices.

At this point, it seems that for a few hundred years – before everything went south in the 14th century – there were peaceful interactions between these Native Americans, based around their religious practices.

Meanwhile, “the reason why it was so special, this is where the Mississippian culture began, right here, and then it spread through the rest of the Illinois valley,” he said. “When Cahokia was being built, so was this site.”

Indeed, it may have predated Cahokia. “It’s like saying everything in Peoria is derivative of Chicago. That’s not true,” said Wilson. “Peoria has its own contributions. It was the same 1,000 years ago.”

In part, the scientists have central Illinois resident Kerwin Brown, a former teacher of welding at Metamora High School and Illinois Central College, to thank for this find. Brown, who’d been walking these fields since he was a kid 50 years ago as a “surface collector” of artifacts and amateur archeologist, had reached out to a contact at Dickson Mounds — Duane Esarey, who would become its director — that the area was full of platform, rectangular mounds. That was some 20 years ago. Eventually, Esarey got word to Wilson, an expert on the period.

“I didn’t believe him,” at first, said Wilson. What followed was a peek at some satellite images, and then he came to see for himself. Next came others with shovels, and the expertise to uncover history with care and respect. Brown was among the volunteers, along with retired Richwoods High teacher Lynn Carl, who was on site recently sifting through the recovered soil for various artifacts.

Many of these sites, like this one, currently are being farmed, and others are threatened by urban development. “Once it’s gone, it’s gone,” said Wilson. “I’d like to save it.”

It’s critical to preserve them for the lessons they unleash, which are as relevant today as they’ve ever been, said Brown, whose life’s work has centered around studying issues of social inequality, identity politics and violence in pro-Columbian North and South America. Sound familiar?

“Thinking about the new situations people find themselves in when migrating and interacting, they don’t know each other, they don’t have a shared history, they’re people who often have fought each other,” he said. Somehow, the early Mississippians “bury the hatchet … They found a way to get along. At least in this case, it was through religion. It didn’t last forever.”

This part of central Illinois is ground zero for some of this research, rediscovery and self-discovery. Soon Wilson and his team will begin exploring another mound center about 10 miles away in Tazewell County, from a period of drought and warfare. Meanwhile, Peoria Riverfront Museum CEO and President John Morris is in conversations with the Smithsonian to return the Peoria Falcon – an ancient copper ornament or armament, 1,000 years old or more, believed to have been worn by a Native American dancer — to its rightful home. East Peoria’s Spring Creek Preserve contains ancient Indian mounds that hikers can get to and glimpse on its miles of paths.

All told, it’s a reaffirmation of the Peoria area’s “hub of the universe” bona fides, and arguably a reminder that, as always, those who forget or never knew the lessons of history are condemned to relive it.

“We have so much more to learn,” said Wilson.