The heartbreaking story of Rhoda Derry, and of the Peorian who came to her rescue

The lore of Rhoda Derry is tragic and disturbing.

Her reality was worse.

A young beauty, she supposedly lost her mind to love. According to sensational headlines, the mother of her betrothed objected to the romance and cast a bewitching curse that pushed Derry into decades of tormenting madness.

According to official records, Derry’s insanity went largely untreated amid the lackluster to nonexistent mental health care of the 19th century. She ripped out her eyes and bashed out her teeth while languishing 40-plus years in a cramped cage.

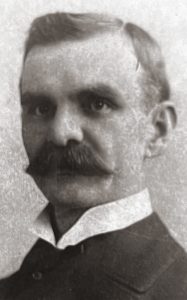

She would spend just the last two years of her life in soothing care, thanks to the reform approach of Dr. George Zeller, head of the Illinois Asylum for the Incurable Insane in Bartonville. Though experienced with severe cases of insanity, Zeller was floored by Derry’s forlorn state. As he recalled in his autobiography, “For inhumanity, nothing has even been heard to equal the treatment afforded this poor girl.”

A ‘happy and healthy’ beginning

Rhoda Derry came into the world on Oct. 10, 1834 in Fayette County, Ind., the youngest of nine children of Jacob and Rachel Derry. The household would later move to farmland in Adams County, Illinois, in Lima Township, about 10 miles north of Quincy along the Mississippi River.

There are scant official records of her youth or family. A 1904 report at the Bartonville asylum noted her father and mother as “physically healthy.”

Newspapers exploited Zeller’s open-door policy, which encouraged publicity of the asylum’s groundbreakingly compassionate care. Before and after Derry’s death, reporters so often wrote of her case that readers statewide knew her by the nickname “Rhody.”

The Rock Island Argus and Daily Union of Nov. 21, 1906 reported, “There was a time more than a half century ago when Rhody was as young and rosy and happy and healthy as any girl in Illinois.” According to the Quincy Weekly Herald of Nov. 30, 1906, “It is said she was a very beautiful girl before she became insane.”

Though some coverage was objective, often leaning on interviews with Derry kin, some prose would turn purple, such was the journalism of the day. That Rock Island report painted her as a “horrible remnant of humanity,” “terrible travesty of human form” and “piteous human wreck.”

‘all at once poor Rhody changed from a merry girl to a raving maniac.’

The cause of her woes? The newspaper did not say, aside from this vague conjecture: “It was when she was still a robust young woman of hardly 23 years of age when some hereditary taint in her blood, some remote disorder transmitted by some long dead and gone ancestor perhaps, suddenly manifested itself, and all at once poor Rhody changed from a merry girl to a raving maniac.”

Officially, the asylum listed her cause of death as “general paralysis of the insane,” suggesting a long-term brain infection. Documents also noted elements of “witches” surrounding Derry, which might’ve hinted at a hereditary malady – or at the folklore regarding her insanity. Asylum records noted that “her mother believed in witches and used to shoot at imaginary witches around the house.”

That witchcraft angle was reported without attribution in multiple newspaper accounts. The Quincy Weekly Herald blared the headline: “Witches Stole Rhody’s Reason: The Weird Life Story of Unfortunate Rhoda Derry.”

A romance gone wrong

According to that tale — repeated elsewhere — the teenage Derry had fallen in love with a young Charles Phenix, their relationship heading toward marriage. But his mother, for reasons unclear, objected and put a curse on Derry.

“All through her insanity, she claimed she was bewitched by an old woman, a neighbor, named Phenix,” the paper reported.

Days after the curse, Derry supposedly told her family that she had spotted Satan lurking in physical form — “something like a wild beast, which she believed was the ‘old scratch.’” Later, while visiting a sister, Derry “said she could see Mrs. Phenix in the corner and that she believed that the old woman would torment her as long as she lived and that her pleasure was forever done.”

For whatever reason, the relationship with Charles Phenix ended. Also, for whatever reason, Rhoda Derry went mad.

Treatment worse than the disease

At the time, Illinois was in the rudimentary stages of caring for people with mental and emotional challenges. In 1851, the Illinois State Hospital for the Insane opened in Jacksonville. Five years later, with Derry’s condition deteriorating, her father took her there.

“In 1856, she became unmanageable,” reported the Quincy Weekly Herald. “She was taken to Jacksonville and while there the authorities could not keep the doors of her room locked, nor could they keep her tied with ropes. They would lock the doors at night, but in the morning Rhoda would be out in the yard walking about. When asked who let her out, she said Mrs. Phenix. When the keeper of the asylum brought her back, she said she was not insane, but she did not know what was the matter with her. She was like the man referred to in the New Testament who lived among the tombs.”

Although the asylum was said to be benevolent, it had no answers for anyone with issues so severe and no system of long-term care. After two years, according to state law, “incurables” were to be sent home to their families.

Thus, Derry returned to Adams County in 1858. Two years passed. She did not improve, suffering from constant “spells” followed by “a beautiful song” and “a solemn prayer” in which she would ask God “to forgive her,” according to Quincy’s Herald.

At the time, the only remaining option for the “incurable” was an almshouse, or county poorhouse—a last-chance residence for the destitute, but little else, certainly no care.

‘Send her along. God bless her.’—Dr. George Zeller

Few cases were as dire. Zeller’s autobiography described Derry’s alarming behavior— tearing off her clothes, eating anything she could grab and harming herself—along with the almshouse’s draconian methods of restraint, keeping her inside a cage-like box known as a Utica crib.

“For years she lived in a basket of straw cared for solely by other feeble-minded patients,” Zeller wrote. “During this time her limbs became drawn up until her knees almost touched her chin. There they remained day after day and week after week until the muscles became atrophied. It was impossible for her to move either her legs or her hips.

“After a while the basket of straw was dispensed with and a square box set on her legs… This box had holes in it so that the excretions would drop into a pan beneath. Mice and other vermin crawled into the box, made their nests and reared their families at the very side of the poor creature.

“Under such treatment her malady became more pronounced. With her long fingernails she scratched her eyes out. With her fists she beat her face until all her front teeth had been knocked out. She lost, to a degree, the power of speech… Placed on the floor she hopped along on her hands, so doubled up that she looked more like a toad than a human being.”

One more, blessed stop

As part of Illinois’ push toward mental health reform, in 1902 Zeller was named director of the new Illinois Asylum for the Incurable Insane in Bartonville.

Told of Derry’s extraordinary case, he traveled to Adams County for a first-hand glimpse. Back at the asylum, he dispatched an official directive to the almshouse: “Send her along. God bless her.”

Upon arrival in September 1904, Derry was bathed and set in her own bed for the first time in 44 years. Though unable to see or communicate, Derry seemed soothed by the delicate hand of care.

“She immediately became the object of solicitude on the part of the nurses and she had never been a moment out of their sight,” Zeller later wrote. “No nurse ever complained because of the demands made upon her time for the caring of Rhody.”

Newspapers wrote widely of her extraordinary case. Derry seemed nonplussed by the attention, though she would smile at the sound of Zeller’s voice. When she died on Oct. 9, 1906, one day short of her 72nd birthday, newspapers rehashed her life’s story. One element of her passing seemed to elude those obituaries. Though the asylum had a profound effect on Rhoda Derry, she returned the favor.

“The nurses who cared for her in life were at the side of the grave when last honors were paid her,” Zeller wrote. “And, when they returned to their duties, instead of feeling a great burden was lifted from their hands, all were crying. The impression of a humane service, dutifully rendered, has shed its halo about them. And the institution is better for having cared for her. The state is better for the knowledge that justice was finally done this long neglected woman.”

‘The institution is better for having cared for her. The state is better… that justice was finally done’—Dr. George Zeller

She was laid to rest under a cement marker labeled simply 217. Eighty years later, family put a marble tombstone atop her grave, with an epitaph that would’ve made Zeller proud:

“They built this place of asylum so that no other human would suffer as you. You taught us to love and feel compassion toward the less fortunate. May you find peace and warmth in God’s arms.”

Some information for this story was provided by 44 Years in Darkness by Sylvia Shults and by the Peoria State Hospital Museum.