Bill Kennedy was a 24-year-old B-24 navigator on December 2, 1944, when the second lieutenant’s plane was shot down. He spent months in a prisoner-of-war camp, where the crowded rooms wouldn’t allow them all to stand at the same time. This unforgettable experience was almost overlooked until a few people happened upon keepsakes about to be discarded after he died. This month, when the nation marks Veterans Day—as well as the 101st anniversary of Kennedy’s birth and four years since his death—is an appropriate time to remember the longtime Peorian.

Unearthed Records

There are other noteworthy World War II combat veterans, but fewer each month remain with us, and the circumstances of Kennedy’s military service are stirring. While his obituary offered a few details, it took records from the National Archives and military researchers to piece together a fuller picture for curious, caring neighbors.

“A friend was clearing out a house where over the past couple of years a family he knew all passed away, and he was trying to help distant relatives get rid of everything,” explains Craig Moore, whose Younger Than Yesterday record/memorabilia store is a few blocks away.

Kennedy’s wife Mary died in January 2017, and 10 months after Kennedy’s November 2017 death, their son Kevin passed on. The family cat fled the empty house, and after being alone in the house for days, their chihuahua Oliver was rescued and adopted. “Their son collected records and shopped here,” Moore says. “After he died, some of his records and his dad’s mementoes made their way to me.”

Kennedy’s wife Mary died in January 2017, and 10 months after Kennedy’s November 2017 death, their son Kevin passed on. The family cat fled the empty house, and after being alone in the house for days, their chihuahua Oliver was rescued and adopted. “Their son collected records and shopped here,” Moore says. “After he died, some of his records and his dad’s mementoes made their way to me.”

Kennedy’s decorations included an Air Medal, awarded for meritorious achievement in aerial combat. “None of this appeared to mean anything to anyone,” he continues. “His Purple Heart, to me, is priceless. I didn’t know this man, never met him or his family. But I had a dad who came back from World War II with a Purple Heart.

“There is no one to carry on Kennedy’s story,” Moore adds, “to cherish these priceless souvenirs of a heroic youth. These men saved the world, men and women who absolutely were and remain the Greatest Generation.”

Missions Overseas

Records show that Kennedy enlisted in 1942, served with Army Ordnance in Chicago (where he met his future wife), and was shipped to Europe in August 1944, where he was assigned to a B-24 crew. “Bomber crews faced tough odds and horrendous conditions,” wrote Richard Bauman in Aviation History magazine. “Not only were the Germans trying to blow them out of the sky, they had to perform their jobs in the cramped confines of brutally cold aircraft—hours of high-altitude flight at temperatures of 50 below zero.”

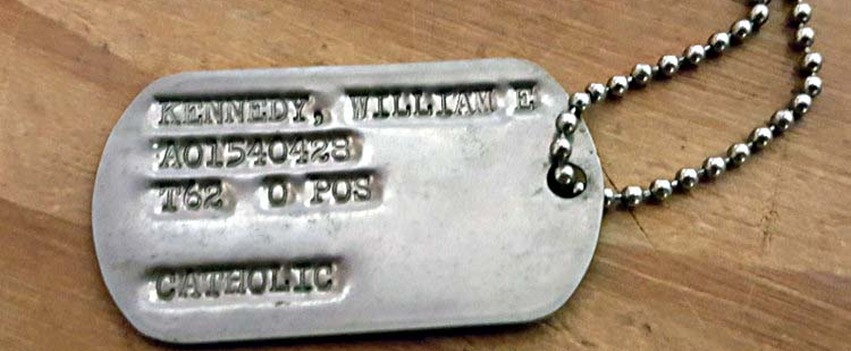

Based in Cerignola, Italy, Kennedy and crew in the 15th Army Air Corps, 55th Bomb Wing, 464th Bomb Group had bombed targets in Italy, North Africa and Sicily. By early 1944, Kennedy had flown 19 missions; and while the military originally designated 20 as the limit for aerial combat duty, that was increased with better defenses and less Nazi resistance. In 1944, the number was 35.

Elsewhere, the Allies on December 1 took Linnich, Germany, east of Dusseldorf, and the day of Kennedy’s last mission, the Ninth Army overran Leiffart, southeast of Munich. That morning, the B-24—number 41231, called “Yellow How” or “Yellow H”—was to fly 1,000 miles from their base and bomb an oil refinery at Blechhammer, Germany. But anti-aircraft fire struck the plane. Records show that eight of the 10-man crew bailed out, with two managing to crash-land the B-24 north of Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, between Budapest and Krakow. Presumably those two were pilot George Matheu and Kennedy, who’d suffered a head injury.

Captured by Nazis

After Kennedy’s wounds were dressed, the crew was captured and moved by horseback to a Nazi hospital, then transferred to a POW camp 600 miles away: Stalag Luft 1 outside Barth, near the Baltic Sea. Kennedy was imprisoned with 9,000 other American and British prisoners—2,500 of them crammed into the camp’s North 3 compound, where Kennedy was one of 26 men in Room 6 of Block 306 in Barracks 6 there. (The award-winning 2017 movie Instrument of War is based on Stalag Luft 1.)

After months of no news about Kennedy beyond a Missing Air Crew Report, the Red Cross notified his parents Daniel and Josephine in Chicago of his survival. It was a miracle; some 6,500 B-24 and B-17 bombers were lost in Europe, with 23,000 killed in action, but he was one of about 26,000 captured.

The war in Europe would end that May 7, but on April 30, with the Russian army advancing, POW commander Oberst Warnstadt ordered the prisoners to evacuate. The senior U.S. officer, Col. Hub Zemke, refused, and Warnstadt relented. The next day, the prisoners awoke to find the Nazis gone. The 2nd White Russian Front of the Red Army arrived later that day, after which prisoners were transferred by air to Camp Lucky Strike in Le Havre, France. It was there, weeks after his liberation, that Kennedy wrote his parents to reassure them, mention that he’d met a priest who knew the family’s parish priest, and express disappointment in the delays coming home: “I was told that I could expect to be here from seven to nine days,” a surviving letter reads. “Tomorrow it will be three weeks.”

Never Forget

After the war, Kennedy married Mary in 1946, graduated from Loyola in less than three years, and worked in Chicago before moving to Peoria in 1954, when they built their house on Virginia Avenue west of University Street. He served in the Illinois Air National Guard and worked in the car business before a 25-year career at Caterpillar. Kennedy remained a devout Catholic and began running year-round and competing in races like the Steamboat Classic.

His was a memorable life, from being jailed in cramped quarters by the Nazis to running free. “I promise to treat this man’s history—our generation’s parents’ history—with the greatest respect,” Moore said. “The majority of these good people are gone now, but I will never, ever forget.” PM