Between COVID, social media and other pressures, many children are stressed, and school districts are stepping up.

“Some students just need to eat, come to school and they’re ready to learn,” said Alyssa Hart.

But for millions of American children, it’s not so simple.

Every day, young people come to class troubled by life issues or mental health conditions that prevent them from being able to concentrate and to learn at their full potential.

For the last two decades, Social Emotional Learning (SEL) curricula have been instituted in schools across the country, identifying students in need of counseling, support services and/or special accommodations to help them get the most out of their school day.

Its goals are to help students develop social and self-awareness, self-management, relationship skills and responsible decision-making abilities. The curriculum, meanwhile, assists school staff in identifying students in need of extra support, as well as providing activities and conversation starters for teachers trying to reach kids and build a rapport with them.

But it all begins with relationship building.

‘If students are happy, fed, loved, they’re going to produce.’

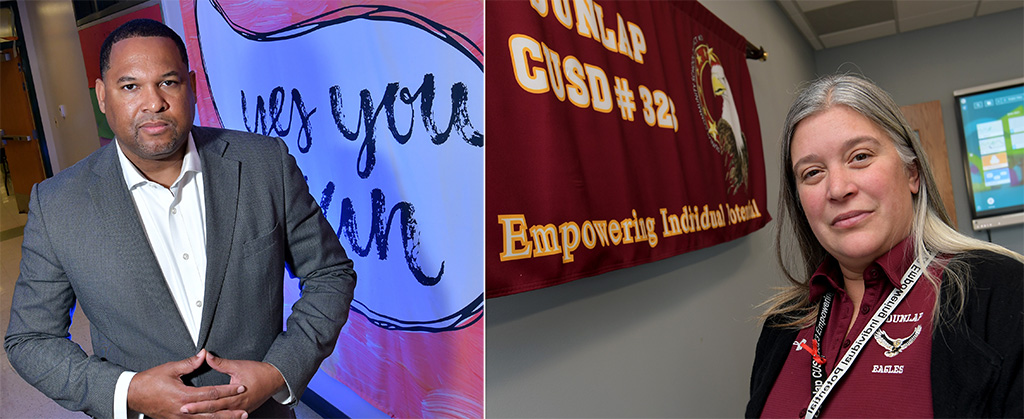

Student needs vary, said Hart, director of student services at the Dunlap School District.

“Some may need a coat or they need food on the weekend,” she said. “If students are happy, fed and feel loved, they’re going to produce so much more for you.”

Dunlap tests students in third through ninth grades three times a year, evaluating them for signs of the need for an individual education program.

“If a student has anxiety or depression, does that student need extra time on a test? What’s it going to take for that student to be successful?” Hart asked.

Other accommodations may include giving a struggling student access to breaks, preferential classroom seating to limit distractions, study guides before a test, and/or a staff member they can talk to.

“We want all kids to graduate,” Hart said. “We want to make plans for them after high school.”

The numbers tell a heartbreaking story.

The State of Illinois requires every school district to develop a policy for incorporating social and emotional development and protocols for responding to children trying to cope with life’s challenges.

Michelle Coconate, director of social emotional support services for the Peoria Regional Office of Education, points to mental health information from JAMA Pediatrics highlighting the need for SEL:

3.85 million U.S. children have unmet mental health needs.

Only 51% of U.S. children and youth with a mental health problem actually receive mental health treatment.

Nearly three-fifths of students receive mental health services in a school setting. Schools often function as the de facto mental health system for children and adolescents.

The most devastating statistics relate to suicide rates.

Coconate refers to America’s Health Rankings website, which notes that in 2020, suicide was the second-leading cause of death among people ages 10-24 and 25-34. Meanwhile, youth suicidal ideation, attempts and completion have been increasing since the turn of the century. Results from a 2019 youth behavioral risk factor survey show that 18.8% of high school students seriously considered suicide and 8.9% attempted it.

The COVID effect

Earlier this year, Illinois increased its emphasis on social emotional classroom learning by allocating $7 billion in federal relief money to school districts, in an attempt to offset the academic and mental health fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Educators and administrators in Peoria and nearby school districts meet regularly to make local determinations for how best to spend the money on behalf of students and staff returning to the classroom, some for the first time in two years.

“We look at data and create action plans based on the needs of each school,” said Coconate. Included is staff care, which “acknowledges the impact of secondary traumatic stress on the staff.

“Is everybody supporting one another? If we don’t have healthy adults, it’s hard to have healthy children.”

Dunlap schools currently employ five elementary counselors, two at the middle school and five at the high school. There also is a mental health counselor for staff.

Between illnesses, the challenges of remote learning and the changes in day-to-day life, “we’ve seen a rise in anxiety and depression,” said Hart. Many students also fell behind academically.

“Now they’re jumping in at a level they’re not prepared for, and they’re overwhelmed,” Hart said.

Meanwhile, many educators voice concerns regarding the negative effects of social media, which started well before COVID and where bullying and ridicule can be commonplace, targeting vulnerable adolescents who may lack the perspective and maturity to deal with it.

In Peoria, embedding SEL ‘everything we do.’

SEL curriculum is established in all Peoria Public Schools buildings, with a staff of 15 social workers, 35 counselors, 11 psychologists, 13 SEL aides, seven therapists, six SEL facilitators and 22 certified occupational therapy assistants.

Derrick Booth, EdD, director of social emotional learning for Peoria Public Schools, stresses the importance of one-on-one relationships with students.

“Putting a student with a check-in, check-out adult in the building can help the student set goals for attendance, behaviors and academics,” he said. The daily attention can help a student stay focused on “one thing I can improve today.”

Booth does not see SEL as “one more thing for teachers” but as a best practice “that many teachers are already doing.

“We look at, how can we embed SEL in everything we do?” Booth said. “The essence of SEL is building relationships. That’s the core throughout, whether it’s in classroom instruction, speaking with students in the cafeteria or walking through the hallways.”

To students, Booth stresses the foundational skills necessary to be successful in life, which are a big part of the SEL curriculum: conflict resolution, problem-solving, positive relationship building and respect for one another.

Families need to be involved, too.

Building relationships with students requires doing so with their families, as well.

To that end, in 2018 the district opened The Wraparound Center inside Trewyn Middle School, a one-stop support source for all members of the community, with an emphasis on the 61605 ZIP code. The latter is among the most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Illinois, and the 42nd poorest in the nation, said Booth.

“The first year the center opened, we hired more counselors, social workers and expanded relationships with other agencies,” said Booth. The Center’s food pantry is its “anchor institution.”

“Once they get to know us at the weekly food bank, they ask for help with getting beds, they mention their son needs counseling, or ask if we can help them get a job,” he said. “If you need anything and don’t know where to go, we’ll connect you with meeting that need.”

One of the Wraparound Center’s partners is OSF HealthCare, which administers the Strive Trauma Recovery Program. OSF Strive offers treatment for victims and witnesses of violence, as well as for those living in the same household. The Wraparound Center also offers justice advocates and an attorney for PPS students charged with a crime.

Currently, 153 students are in that program, which also helps to keep participating students enrolled in school, follow court orders, get a job or engage in another activity, and stay on track to graduate.