These violins escaped the Holocaust, telling a story that goes well beyond the beautiful music they’re capable of

Linda Leeser did not know what to do with her father’s violin.

The instrument was shrouded in unspoken mystery. He had played the violin, but not since her birth, perhaps longer, perhaps not after he joined many Jews in fleeing Germany ahead of the Holocaust.

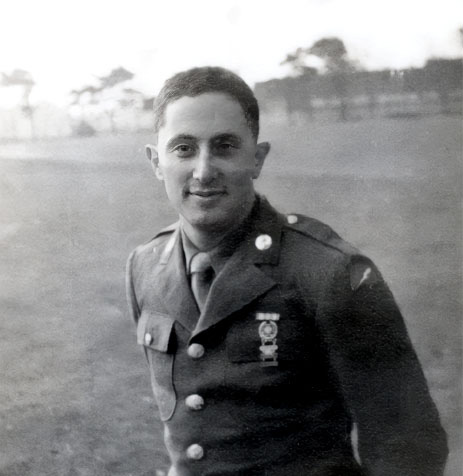

during his service with the U.S. Army (Photo provided by Violins of Hope)

Paul Leeser came to America and served overseas with the U.S. Army in World War II. Afterward, he never spoke of his service or the violin. It sat untouched, even after he died at age 60 in 1981. As almost four decades passed, Linda Reeser remained unsure what to do with the violin.

“I couldn’t sell it. I couldn’t just give it away,” said Reeser, 75, of Louisville, Kentucky. “I was just hoping its day would come.”

That happened in 2019, when she heard about Violins of Hope, a touring exhibit of restored instruments connected to the Holocaust. She contacted the organization, and in doing so, finally found its proper place.

“I appreciate that these violins are given a home and honor,” she said. “I feel like I’m doing something in honor of my father.”

Coming to America’s heartland

Paul Leeser’s violin is one of 10 instruments coming to the Peoria Riverfront Museum with Violins of Hope, started by Israeli violinmakers Amnon Weinstein of Israel and his son, Avshalom Weinstein of Istanbul. Over 20 years, they have rehabbed 70 violins, violas and cellos donated from around the world. Each instrument tells a story tied to the atrocities committed by the Nazis. Just as important, each quivers with the themes of resistance and resiliency.

“We have to try and keep the stories alive,” Avashalom Weinstein said. “We’re trying to bring these stories of regular people who had to try and survive. Some did. Some didn’t.

“Doing it with their own instruments and stories helps, we think and hope, for people to understand that these were people like us.”

The exhibit comes via a partnership between The Jewish Federation of Peoria, Peoria Riverfront Museum and JCC Chicago, the latter of which devoted significant effort and resources to making the Violins of Hope exhibit happen.

An incredible journey

Some of the violins were played inside concentration camps where prisoners were often forced to entertain the Germans stationed there. One of the violins — which will appear in Peoria — escaped that destination, but perhaps its owner did not.

In 1942, thousands of Jews were arrested in Paris and sent by cattle rail car to concentration camps, most of them to Auschwitz. On one of the packed trains, a man clutched a violin. At a brief stop along the French countryside, he heard rail workers outside, so he cried out, “In the place where I now go, don’t need a violin. Here, take my violin so it may live!”

He did not know that the instrument could very well have boosted his chances for survival, as musicians were often spared at the camps. Through a narrow train window, he flung his violin, which was retrieved by a rail worker. For many years, the violin sat ignored in an attic. When the rail worker died, his offspring sold the instrument to a French violin maker, sharing its backstory in the process.

When the violin maker heard about Violins of Hope, he donated the instrument. Though its 1942 owner — along with his fate — remains a mystery, his violin once again lives.

“We have to make sure that the stories and memories are known, so we can try and not make the same mistakes as were done before,” Avshalom Weinstein said.

The story of Paul Reeser’s violin remains unclear. Born in Hanborn, Germany in 1921, he came with his family to the United States in 1937 as conditions for Jews in Germany were deteriorating. He graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Cincinnati before taking a job with a tool company in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin.

He enlisted in the Army and headed overseas, where he likely served as an interpreter, possibly behind enemy lines. Aside from bringing home a few photos and Army mementoes, his family was never sure of his military record, as he never discussed it.

“Ours was a family that didn’t talk about the past,” his daughter said.

Four years ago, she gave the violin to Avshalom Weinstein, who could tell it had been made in Germany around 1898. He repaired a crack in the wood and restrung the bow, then added the violin to the exhibit. Though Linda Leeser has yet to see the traveling collection, she is gratified to keep alive the legacies of the violin and her father, as well as the Jewish spirit of survival.

“I’m just glad I can do something in his memory,” she said.

All lines intersect in Peoria

Meantime, there is a local connection to Violins of Hope.

Some of the violins were played by members of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, now the Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra. It was founded in 1936 by famed violinist Bronislaw Huberman, who was well aware of the rising dangers to Jews in Germany and nearby nations. He persuaded 75 of the area’s finest Jewish musicians to come to Palestine to join the orchestra, saving not only their lives but those of more than 900 family members.

Huberman, who died at age 64 in 1947, was related to the father of Jeffrey Huberman, the current dean of Bradley University’s Slane College of Communications and Fine Arts. He marvels at Bronislaw Huberman’s ingenuity in rescuing so many people.

“His story is really quite remarkable,” said Huberman, 75.

He looks forward to his first glimpse of Violins of Hope, some of which will be played at orchestra performances in Peoria.

“They still survive,” he said. “They still make music. They still speak to us in an international language.

“These violins survive for other artists to speak from them. They carry with them an incredible history.”

Violins of Hope

August 4–31, 2023

Peoria Riverfront Museum

August 3, 2023

Private Opening Reception

5 to 7 p.m.

August 4, 2023

Violins of Hope Exhibition

10 a.m.

August 6, 2023

Suzuki School of Music presents Instrument

Petting Zoo

1 to 2 p.m.

August 10, 2023

The Jewish Federation of Peoria presents a performance of the Heartland

Symphony Orchestra

August 27, 2023

Peoria Holocaust Memorial

20th Anniversary Celebration

Doors 3:30 p.m.

Performance 4 p.m.

August 31, 2023

Violins of Hope Exhibition Closes