For 123 years, Peoria’s NAACP has been making waves and producing needed change.

The Peoria branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in 1915. The best explanation for why the organization formed may have appeared in a Peoria Transcript piece in 1914.

Headlined “Negroes of Liberty Party Act: Demand Political Recognition,” the bulletin from the Liberty Party, a small political organization at the time, declared that African Americans were being left out of the Peoria economy.

“There is not a Negro employed in the court house in Peoria County,” the newspaper piece read. “There is not a Negro policeman walking a beat in Peoria. There is not a Negro fireman in the fire department in Peoria.”

Peoria’s African American population was much smaller at that time, with the 1910 census listing 67,000 Peoria residents in total, of which only 2.3% were black, about 1,500 people. It’s also worth noting that it took decades for the vacancies cited in the 1914 article to be addressed, largely due to efforts by groups like the NAACP.

Charles Ruff was Peoria’s first NAACP president, followed by Birdie West, its first female leader, in 1923. The organization’s early years were focused on supporting national anti-lynching legislation, which incidentally did not become law until 2022.

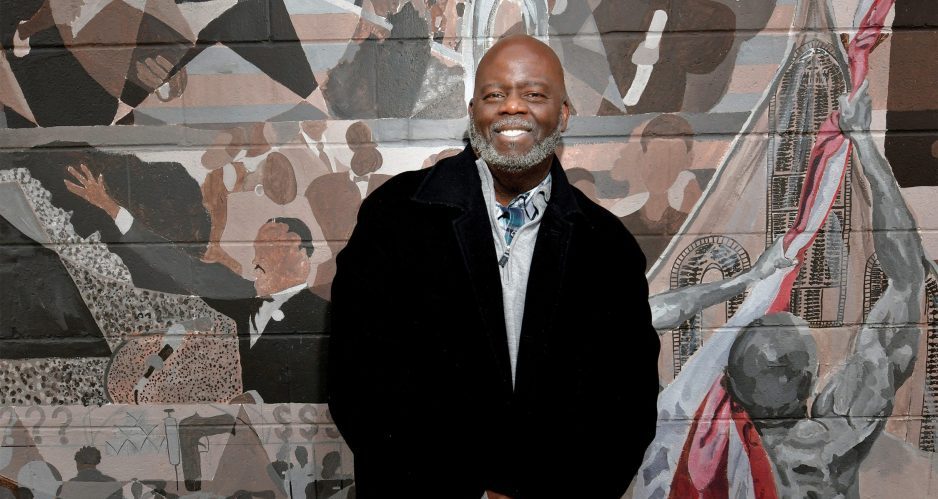

Civil rights and local employment issues have remained NAACP concerns for more than 100 years. The Rev. Marvin Hightower, the pastor at Liberty Church of Peoria, has led Peoria’s NAACP efforts since 2017.

Despite progress on many fronts, Hightower said the fight for equality goes on. “I’m surprised to find some battles I thought we won — involving labor, housing, education — continue to be issues,” he said.

‘If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu. You need to voice your opinion.’— Rev. Marvin Hightower

“One of the things we do now is write policy with public entities to make sure minorities have access,” said Hightower. “If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu. You need to voice your opinion.”

Hightower recalled when John Gwynn Jr. headed Peoria’s NAACP from 1961 to 1993, a period marked by activism, particularly in the 1960s and ‘70s. “We do it a different way now,” opting for consultation and recommendations instead of marches and sit-ins, said Hightower.

“There’s nothing wrong with activism but we try to work behind the scenes,” he said, noting that a present project involves ensuring that minorities get their fair share of construction jobs in the new health department to be constructed by Peoria County.

Don Jackson, still active as a Peoria attorney, headed the NAACP chapter in Peoria for more than 20 years, from 1996 through 2016. Without the NAACP, “so much of what has changed would not have come about,” he said, crediting past NAACP leaders such as Harry Sephus and Gwynn as true pioneers. “The groundwork was done when I came to office,” said Jackson.

“Sephus got a call from Caterpillar in the early ‘50s. They had a long discussion about employment. After that, the company started recruiting African Americans from the historic black colleges. Previously the only job for blacks at Cat was sweeping floors,” said Jackson, who would work briefly as timekeeper at the Caterpillar foundry in East Peoria.

Before opening his law practice in Peoria, Jackson worked with Gwynn at the post office. “I supported John 100 percent. He really put pressure on everybody in this city,” he said.

During Jackson’s tenure, “the issues were mainly employment — public and private — to get people in meaningful jobs,” said Jackson. After Black officers got on the Peoria police force, it was important that qualified individuals received promotions like their white counterparts, he said.

“We had to threaten a lawsuit to get African Americans promoted to sergeant. Melvin Little, now retired, was one of the first African Americans to become a sergeant at the police department,” added Jackson.

Jim Ralph, a professor at Middlebury College in Vermont and the author of Northern Protest: Martin Luther King, Jr., Chicago and the Civil Rights Movement (1993), has made an extensive study of the NAACP branch in Peoria.

“Arguably, it’s the most dynamic branch in Illinois. For 20 years it was the most dynamic in the country,” he said, referring to the period when Gwynn sought change in the ‘60s and ‘70s. “It wasn’t just a one-man show with Gwynn, but he was a critical element. He involved a large number of people, black and white. His wife was a force, as well,” said Ralph.

“Gwynn was not an orator in the style of Martin Luther King or Andrew Young but he was very compelling. He was a man of the church and well acquainted with the institutions of Black Peoria,” Ralph said of Gwynn, who died at the age of 67 in 1996.

In an interview with Peoria Magazine in 2015, a year before his death, Jim Polk, the first African American elected to the Peoria City Council in 1969, talked about his experience with the NAACP: “Before I left Peoria (to return a few years later), John Gwynn and I took over the Peoria NAACP. I was vice president — I was probably 21. There were a lot of young people back then in the movement. The NAACP was really important and really active.”

Ralph, who has made numerous trips to Peoria to conduct research, looks to publish a more extensive look at Illinois civil rights organizations. “The NAACP hasn’t received the credit it deserves,” he said. “It’s helped lead to change.”