Carl Porter Jr. fought valiantly for his country, married the love of his life, and made his little corner of the world a better place

In Peoria, a quiet hero died a quiet death.

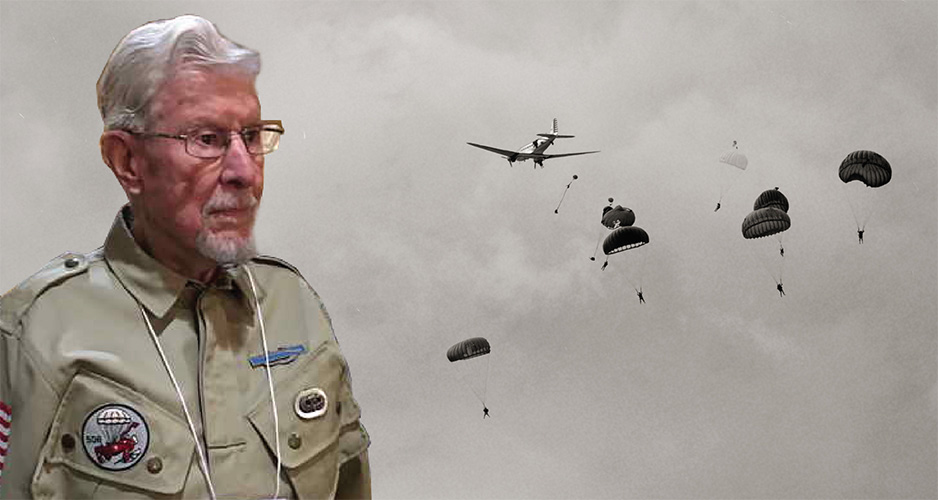

Carl H. Porter Jr. — the oldest veteran of the Army’s 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and a survivor not only of a D-Day jump but his capture by Nazis — died in February at age 101. Though humble, Porter was deeply proud of his service to his country.

magazine included a story regarding

a World War II firefight that ended

with the freeing of 13 captured U.S. paratroopers, including Carl Porter

But aside from family and friends, not many people knew his name. I think more should.

On Aug. 30, 1921, Porter was born in Manito, then moved with his family to Pekin, where he later worked with his father at a grain elevator along the Illinois River. After World War II broke out, Porter enlisted in the Army and volunteered to become a paratrooper. He served as a rigger and maintenance specialist, entrusted with the important duty of packing and maintaining parachutes. But he also trained to jump as part of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

At 2:15 a.m. June 6, 1944, under bright moonlight, Porter peered out of a low-flying C-47 transport plane flying low above France. The 508th joined the 82nd Airborne Division in Operation Overlord, jumping into Normandy. Floating downward, Porter watched German tracer bullets crisscross the sky, with multiple rounds searing through his chute.

‘I looked up and there were three Germans … guns pointed at my tummy’ — Carl H. Porter Jr.

He landed in a tree. He grabbed his rifle. He wasn’t alone.

“I looked up and there were three Germans, with their guns pointed at my tummy,” Porter later recalled. “So, I just dropped (my) gun.”

At their direction, he raised his hands in surrender. He and 12 other paratroopers were herded into a wide room inside a French stone farmhouse commandeered as a makeshift German base. Outside, the Americans heard the rising roar of rifle and mortar blasts. The 4th Infantry Division, which had quickly seized control of Utah Beach, had arrived at the farmhouse, engaging in a firefight with the Germans — especially those in machine-gun nests — keen on protecting the property.

At first, Porter and the other Americans could do little to resist. Then a German soldier entered the prisoner room, a sour look on his face and rifle in his arms. He peered at Porter to angrily ask his origin: English? Russian? Porter pointed to the U.S. flag on his jump jacket, saying, “American.” At that — for reasons Porter never understood — the German smiled and put down his rifle.

“He grabbed me and gave me a big bear hug,” Porter recalled.

Another paratrooper grabbed the German’s rifle, darted into an adjoining room and promptly forced six enemy soldiers to give up their weapons. Porter picked up one of the discarded rifles and joined his countryman in going room to room to order more Germans to surrender.

Meantime, overmatched by U.S. firepower, the Nazi machine-gunners outside gave up. But the U.S. infantry kept targeting the farmhouse, oblivious to the Americans inside. They waved shirts out the window and yelled for their brethren to stop, but the shelling continued.

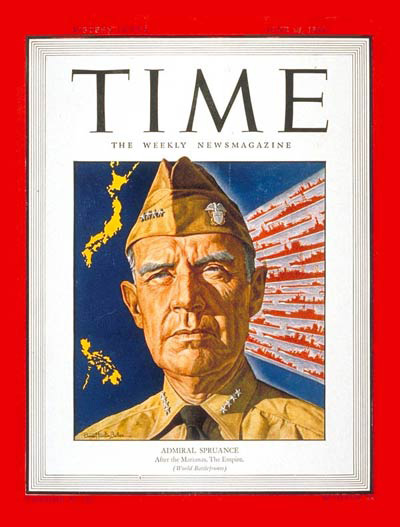

Finally, a paratrooper found a bullet-riddled German bugle on the ground. He thrust it out a window and blared a common tune all U.S. military recognized: “chow call,” played before every meal. At that, the 4th Division realized their fellow soldiers were inside the farmhouse — and stopped firing. That slice-of-war vignette was recounted in the June 26, 1944 issue of Time magazine.

Porter served in the Army through the end of the war, returning home to marry the love of his life, LaSalle native and Bradley University grad Marlynn “Marly” Moeller. Realizing his high regard for his time in the Army — “Carl’s service to his country was the single most important event in his life,” his family would recall in his obituary — she fashioned her wedding dress from a parachute he brought home. They married on March 16, 1946.

On their first anniversary, they took a long trip, by car and steamship, to Ketchikan, Alaska, on the recommendation of an Army buddy who’d visited and loved the place. The Porters agreed — and stayed for decades. Porter went into the insurance business, meantime serving alongside his wife in multiple civic organizations.

‘Carl’s service to his country was the single most important event in his life’

“I have conducted my life — and operated the businesses with which I have been associated — in the most honest, honorable, and compassionate way possible,” he once said.

The couple raised two children in Alaska, which they loved for the woods, mountains and views. After he retired, the couple decided to try life elsewhere in the Lower 48, including Washington, Nevada and California.

In 2011, they decided to return to their roots, moving into the Buehler Home senior-living facility in Peoria. Marly died in 2013 at age 88. They had been married for 67 years.

Despite that loss, Porter still knew several faces there from his younger days, especially cousin Shirley Meagher. As kids, the cousins and their families enjoyed gatherings in Manito and Peoria, but they had lost touch over the decades. At Buehler, they were happy to become reacquainted.

“We go back a long way,” said Meagher, who has lived all of her 100 years in Peoria and East Peoria. “It was just our lives coming together in our old age.”

Buehler recorded some of Porter’s military memories in 2020. The next year, he celebrated his 100th birthday there. He enjoyed mostly good health before passing away on Feb. 18 of this year.

Humble to the end, Porter requested no funeral. Per his obituary, “Carl wanted no fuss, and there will be no formal memorial. His ashes will quietly be laid to rest alongside his beloved wife, Marly.”

Before he died, his family made sure to ask, “What is the one thing you would like to be remembered by?” His succinct reply:

“That I was true.”

Indeed, he was a true patriot, husband, father and friend. Those 101 years were well spent — and why you should know the name of Carl H. Porter Jr.