Photography by David Vernon

The Twin Towers. The Becker Building. Landmark Recreation Center. These are but a few of the iconic structures for which Ray Becker was responsible during his 70 years in the construction business. As president and CEO of The Becker Companies—a collection of businesses to develop, design, construct, finance, market and manage his various real estate ventures—he’s built homes, condominiums, hotels, warehouses, churches, schools, prisons, office buildings, shopping centers, nursing homes… and the list goes on.

A 1949 graduate of Woodruff High School, the entrepreneurial developer got his start in business as a teenager—after convincing the school board to allow him to work while attending school part-time. He soon began remaking the entire city of Peoria, from sprawling subdivisions on the outskirts of town to towering buildings in its downtown core, and expanding into projects around the Midwest, Florida and Arizona. A pioneer of the design-build construction technique, he was known for getting things done, on time and under budget.

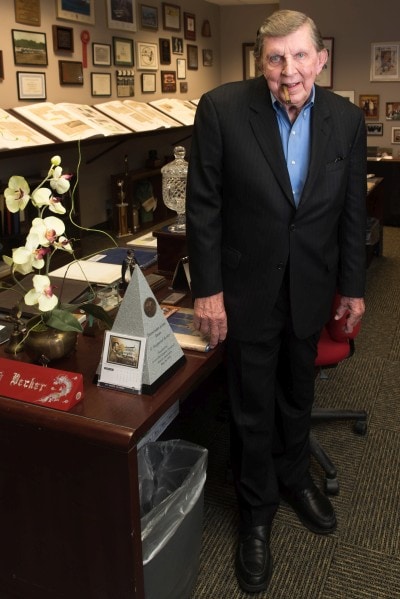

Hundreds of plaques, awards, photographs and magazine articles decorate the walls of his office and spill out into the adjoining hallway, telling tale after fascinating tale of a life well-lived. He’s been a friend to presidents and governors, a generous philanthropist and longtime co-chair of the Easter Seals Telethon, and a community leader through his work at Eureka College, Bradley University, and a range of other nonprofit and

civic boards.

“Whatever happens, they’re going to know I was here,” he once remarked while admiring the 28-story towers that reinvented Peoria’s skyline—and truer words were never spoken. Without Ray Becker, Peoria wouldn’t look anything like what it does today.

Ray, you were born and raised in Peoria. Tell us about those early years.

There were eight of us children, plus my mother and father. We lived across the street from Saint Francis Hospital—that’s the neighborhood I grew up in. We went to St. Bernard’s Catholic Church and School, about a mile and a half up the way. We had a fruit cellar and kept it full all summer long—and that’s what we ate all winter.

We had a big backyard, a hundred chickens and a hundred rabbits. Every once in a while, my mother would hear somebody out in the chicken coop. I’d get my ball bat and go out looking for the guy (laughs). I was a big kid.

World War II started in 1941 when I was 10 years old. Two of my brothers joined the service and a third one went a year later. Another joined the Marines when he was a senior in high school. He died when he was 18 in Okinawa—two weeks before the war ended.

How did that impact you as a kid?

I was never really a kid; I was always working. We were poor. My dad was a cement finisher, and as the war went on, my mom became district manager for the Peoria Star newspaper. All of my brothers worked. I had a paper route when I was 14—we kept it in the family for years. We’d keep passing it down, from brother to brother. And all of us learned to pour concrete.

I hear you got started in business when you were still in high school. How did that happen?

When I was a sophomore, my dad got me a summer job with W.G. Best Homes [a pioneer in manufacturing pre-fabricated homes], where he was finishing the concrete. The summer of my junior year, Best decided to subcontract the concrete work, and my dad said, “Well, that’s the end of that.”

I was 18 years old, but I was ambitious (laughs). So I asked my oldest brother to go into business with me. I traded my car for a pickup truck, went to Central Bank and borrowed $500 to buy the equipment I needed. Then I went to W.G. Best and said, “We’d like to keep doing your work… I’ll go into business for myself and do your basements.” [This was the beginning of Becker Brothers Construction in 1948.]

I was 18 years old, but I was ambitious (laughs). So I asked my oldest brother to go into business with me. I traded my car for a pickup truck, went to Central Bank and borrowed $500 to buy the equipment I needed. Then I went to W.G. Best and said, “We’d like to keep doing your work… I’ll go into business for myself and do your basements.” [This was the beginning of Becker Brothers Construction in 1948.]

He gave me 200 houses on the south side, but I had to work it out with my school. I wanted to graduate with my class, but I needed to be working. So I went to the school board and asked that I be allowed to attend classes in the morning and work in the afternoon. And they approved! That was the first school/work program in Peoria.

I’d attend school in the morning, go home and eat lunch, change clothes, then go to work all afternoon and into the evening, pouring concrete. We did eight to 10 basements a week.

Were you always this ambitious?

I could keep you here all night telling stories! As a boy, I used to take old orange carton crates, use the wood to make furniture, and sell them around the neighborhood. I also swept the school at St. Bernard’s. In the winter, I’d stoke the boilers. I’d get up at 5:30 in the morning, stoke the boilers in the church, stoke the boilers in the school. I was always working.

How did you come to take over the business?

After two years, my brother moved to California and started his own concrete business. I kept the name Becker Brothers, but it was really just me. I was still doing concrete for W.G. Best, but I started building houses on the side. I designed and built two houses, and specced them down in the south end.

About that time, they came out with a new brick called SCR—“structural clay research.” It was the same as a regular brick, but it was a structural brick. And I started building brick homes. I wanted to keep prices down, so I took one of those SCR bricks and adapted it… I used the same amount of clay, but made the brick twice as high, so they could put up a wall much more quickly. We used them all around town—everybody called them “Becker bricks.” I got Peoria Brick & Tile to make them for me, and we shipped them all over the country. My slogan was “Brick or frame, price the same.” My first houses sold for $8,950, and we sold them as fast as I could build them.

When did you get into commercial developments?

In the ’50s, with the filling station at War Memorial and University. It’s still there—Beachler’s. They’ve added onto it two or three times. I built that, and then a [Howard Johnson’s] restaurant across the street at Florence and University.

Were you still building houses, too?

I was doing both. I built over 500, maybe 600 houses in Peoria. We built Holy Family School at Gale and Sterling, and that led to my first subdivision, Holy Family Park. We sold lots and built houses on them.

What was the next company you started after Becker Brothers Construction?

I started the lumber company next, in ’55—the G.R. Becker Lumber Company out on Farmington Road. My brother Chuck ran it for decades.

What was your first project in downtown Peoria?

We built the Sears building and Bishop’s Cafeteria on the same block in 1962. The Ramada Inn complex, near Saint Francis Hospital, was going up at the same time. [The old Sears block is now home to the Peoria Riverfront Museum and Caterpillar Visitors Center; the former Ramada Inn housed Methodist College until it moved to north Peoria in 2016.] That’s a book in itself.

There was also a great need for warehouses at that time—I built four or five in Pioneer Park. We were doing apartment buildings around town, and I got into the blacktopping business with Peoria Blacktop. We did that for a few years, then sold it to a group that included my friend Pete Vonachen [longtime owner of the Peoria Chiefs].

Tell us about building the campus for Illinois Central College when it was founded.

Illinois passed a new law for junior colleges in the mid-sixties, so all these junior colleges wanted to get up and going, but they didn’t have any campuses. So we got involved.

They didn’t know what their classes were going to be; they didn’t know if they were going to have auto mechanics or what. So I designed a building, 100-some feet long, 40 or 50 feet wide. There was an entrance on both ends, and on the inside you could divide them up any way you wanted. I started at ICC and went all over the state building them. I would just go into these board meetings and walk out with a contract. I couldn’t believe it! Most of the time, I’d never even seen the land.

They didn’t know what their classes were going to be; they didn’t know if they were going to have auto mechanics or what. So I designed a building, 100-some feet long, 40 or 50 feet wide. There was an entrance on both ends, and on the inside you could divide them up any way you wanted. I started at ICC and went all over the state building them. I would just go into these board meetings and walk out with a contract. I couldn’t believe it! Most of the time, I’d never even seen the land.

What got you into the nursing home business?

The state changed what they were doing with their hospitals and institutions, so there was a big demand for private elderly care. But there weren’t many licensed facilities available, so we started building nursing homes. This was in the early ’70s.

We formed a company called Lexington House Corporation, which owned and operated a bunch of nursing homes, and we built nursing homes for other owners across the country. Overall, Lexington built 49 such facilities in five different states. At the same time, we were building all these houses in Lexington Hills. It was a 400-acre subdivision, the largest private-property annexation in the City of Peoria at that time. We were a well-oiled machine.

How did you decide what businesses to get involved in?

I just looked for opportunities—I would see a need that wasn’t being addressed. Half the time, people came to me; I didn’t go to them.

How were you able to manage all these different companies and projects?

I had some really good people. John Parkhurst was my lawyer; he was also a [state] legislator at one time. He moved into my office—he was full-time with me. Chuck Ginoli, and later his brother Gene, were my CPAs. And Bill Lanzotti is another great guy—he’s been with me for 42 years.

What was your next big project in downtown Peoria?

The Continental Regency Hotel at Hamilton and Madison [now Four Points By Sheraton]. It was originally called the Voyager Inn. First Federal Savings went into business with this developer out of Springfield who was going to build a big high-rise hotel on the side of the Voyager. The guy ended up digging a big hole in the ground, ran away with all the money, and First Federal was sitting there dead in the water.

So they came to me. They said they’d loan whatever money we needed to get them out of this mess. We had done the Sears building, but this was what really put us on the map from a downtown standpoint. That was 1976. Then we did the Illinois Mutual building—that was a big job. And we bought the old Jefferson Building and the Central Building, and rehabbed both of those.

How did Landmark Recreation Center come together? I hear you were an avid bowler—was that part of the original concept?

I wanted to build a 50-lane bowling alley with all the latest equipment, and I’d bought up that land on Dries Lane. So we built Landmark Lanes. We held the Professional Bowlers Association tournament at Landmark for 20 years; it was nationally televised on ABC Sports.

We also put in a big arcade—that was when Pac Man first came out. Nobody had home computers back then; you had to go to an arcade if you wanted to play video games. That was very successful. We made enough money from that to pay our mortgage every month.

What about the movie theaters?

I had a great relationship with George Kerasotes, who owned all the theaters around central Illinois. We started out with five theaters [at Landmark], and ended up with 12. Then the health club was added on. Finally, we added OTB—the first privately-owned off-track betting parlor in the United States.

Of all of your projects, you are probably best known for the Twin Towers, which opened in 1984 and remain the tallest buildings in Peoria. How did that project come about?

I was up in Chicago on Lake Shore Drive. I saw this high-rise and got the concept of selling lots in the sky. I don’t remember where I got the idea for the name Twin Towers.

Basically you’d have a blank floor, and you could design whatever you wanted: a third of a floor, half a floor or the whole floor. There were only certain limitations, like where the pipes came up for the bathrooms. Whereas in Chicago, you’d have an A unit, a B unit and a C unit that went all the way up the building, and that’s all you had—no flexibility. I liked that I could cut the floor into four apartments, or keep it to one per floor. Peoria had never seen anything like it. And nobody had ever heard of a doorman around here.

Peoria was experiencing a major recession at that time. Why did you think you could buck that trend?

Peoria was experiencing a major recession at that time. Why did you think you could buck that trend?

I just never stopped to worry about it. That was when they had the bumper stickers that said, “Last one to leave Peoria, please turn off the lights.” We put up signs that said, “We’re keeping the lights on in Peoria,” or something to that effect. Everybody said we were crazy. The economy was down the tubes; nobody was taking any risks back then. We were building this big, new residential [building], and nobody even lived downtown!

Wasn’t there some controversy in buying up the property on that block?

That was quite an undertaking—I think it was 18 parcels and 35 different owners. My attorney did an unbelievable job tracking down all those people, and we bought everything up except for one guy who tried to hold out on us. He only owned one piece of property, but he was great in front of the cameras. That made the national news.

[NBC anchor] Tom Brokaw came to Peoria, and my office was on the 12th floor of the Jefferson Building. I remember him standing there, looking out the window. They made it into a “David and Goliath” story—it was more interesting to take the side of the “little guy” versus the “big developer.” He was trying to hold out for big money, but after a while, the price came down and we were able to begin construction.

You talked about building the ICC campus. Tell us about the time you built student housing for Bradley University—that was a unique project.

One year, Bradley had more incoming students than they had housing. It was August and school started in September. They didn’t have enough dorm rooms, so they came to me. I was on my way to Moline with one of my engineers; I had him drive while I designed this building. I priced it out and showed up in [Bradley President] Jerry Abegg’s office—three weeks before school opens. He thought it was a great idea. We looked at part of a parking lot on campus and decided we’d put it there.

We planned to build three buildings in a U-shape—50 rooms, plus bathrooms and everything. I said I’d have it ready by September 1st. I called [Peoria Mayor] Jim Maloof and said, Here’s the plans. Waive the building permit, waive inspections and I’ll get started. The next day, I had my bulldozer out there taking blacktop off the parking lot, and we started digging footings.

This was a big deal—the news would do follow-up stories every day, showing the progress. Nobody believed we could build this thing in two weeks.

I had to find windows big enough so kids could exit through them [in case of emergency]. So I’m calling all my friends, builders that I deal with… and a guy in Detroit called me back. He had 58 windows sitting in his warehouse. I sent my son Ray Jr. up in a truck. By the next weekend, we had the floor built and the walls were going up.

None of the truss companies could get us on their schedule for another month… so I called my brother at the lumber company. I said order the lumber, get it here by the weekend, and we’ll make the trusses ourselves. We worked day and night, all weekend, and we had them done on Monday morning—the same week we put the roof on. It was really something.

What was your connection to Eureka College?

There was a guy from Caterpillar, George Armstrong, who was on their board. He was a good friend of [Ronald] Reagan’s and he told Reagan about me. I got a letter from him when he was governor of California, asking if I would serve on the board. They were in financial trouble at the time. He said, Ray, you have to save my college. What would people think if my college goes bankrupt when I’m running for president? I’d never even been to college (laughs). But I agreed.

After the first board meeting, one of their people took me into his office—his desk was stacked with papers. “This is what we owe.” I couldn’t believe it. At the second meeting, I became chairman of the finance committee. Next meeting, now I’m chairman of the board. That’s when Reagan and I became personal friends. I had his personal number. I was in the Oval Office four times, and he was up in my penthouse twice.

Anyway, I started going through the papers and calling people. “How would you like to make a donation to Eureka College? Otherwise, we’re going to go bankrupt.” Everybody gave to me. That first go-around, we raised $10 million and paid off all their bills. They had never raised $5 million in the history of the college. I put my whole heart and soul into it.

What kept you here in Peoria all these years?

Well, it was my town.

What are you most proud of in your career?

I guess it’s my longevity (laughs). I’ve been in the construction business for 70 years. The Lord’s been good to me.

What was your biggest challenge over the years?

I used to have one nightmare all the time. I’m building something somewhere… but I can’t get it built. I try and try and try, but can’t get it done. That was my big challenge: how to get that building done.

What was your last major construction project in Peoria?

I wanted to do something special to honor my folks, William and Florine Becker. We’re sitting here today on the ground floor of the Becker Office Building, which I built and dedicated to them. I thought it was a fitting capstone to my career: to have a lasting tribute to the people who encouraged me to follow my dreams and never say never. PM