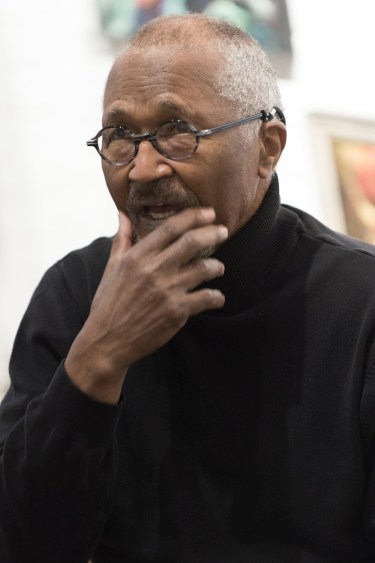

One of America’s greatest artists—perhaps the quintessential artist of our time—has been living and working in the Peoria area for decades. Preston Eugene Jackson is not just an internationally celebrated sculptor and painter; he’s a remarkable guitarist, teacher and martial artist—a master of every medium he touches. Born in 1944, Jackson grew up in a family of ten children in Decatur, Illinois, immersing himself in music and art from an early age. He formed Preston Jackson & the Rhythm Aces as a teenager and toured the chitlin circuit throughout the 1960s—including gigs in Peoria which found him rubbing shoulders with a young Richard Pryor, who was just beginning to develop his groundbreaking act.

Jackson attended Millikin University and earned his B.A. degree from Southern Illinois University. Upon obtaining his MFA from the University of Illinois, he taught at Millikin and Western Illinois University, where he served as professor of art from 1972 to 1989. He then joined the prestigious School of the Art Institute of Chicago as professor of sculpture and remains professor emeritus. He was a pioneer in the mid-nineties redevelopment of the Peoria riverfront, creating a sculpture walk and opening the Checkered Raven art gallery, now the Contemporary Art Center of Peoria.

A prolific artist and performer, Jackson confronts social issues boldly and directly, connecting the hard truths of American history to its present and future, anchored by the common thread of humanity. His sprawling sculptural installations—including “Fresh From Julieanne’s Garden” and “Bronzeville to Harlem: An American Story,” now on permanent loan for display at the Peoria Riverfront Museum—bring historic vignettes to life via hundreds of bronze and steel figures, relief sculptures, automobiles, buildings and the like, its power magnified by the profound written narratives that accompany his work.

Jackson’s public art commissions honor historic figures from Richard Pryor and Miles Davis to Fred Hampton and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., among many others. His monument commissions explore significant historic events, from “Acts of Intolerance,” created to memorialize the 1908 Springfield race riots, to “Knocking on Freedom’s Door,” which commemorates a station along the Underground Railroad in Peoria.

Jackson is a 1998 Laureate of the Lincoln Academy of Illinois, the highest possible honor bestowed by the state upon an individual, and was awarded a Regional Emmy for hosting a television show featuring “Julieanne’s Garden.” Today, he continues to produce extraordinary work that provokes thought and contemplation and calls righteously for justice and equity—leaving behind a legacy that will endure for all time.

Tell us about your family and how they arrived in Decatur. Were they part of the “Great Migration” from the South?

Yes, it was a very common story. They came up here from Trenton, Tennessee. The Livingstons, the Russells, the Jacksons and the Bonds—they were the main African American families in Decatur, the early settlers escaping Jim Crow. We had a big family of 10 people… with just so much love and drama there. As a kid, I recall powerful people, wise and strong. They were the children of slaves. You could tell they came out of this unrest in America during the 1910s and ‘20s [Tulsa massacre, Springfield riot and many others.] But at the same time, people didn’t want to talk about it. That history was fresh in their minds.

We could tell something terrible had happened, the way they didn’t talk about it. And when they did talk about it, it was like, Whoa, you really went through that? My dad used to tell us his grandmother’s tales about how they lived as slaves, how they used to feel those welts on their backs. I always wondered, Should I believe this or should I not? Of course I did, because my parents didn’t lie. They were protecting us… because those stories were very vivid. Even today, I pass them on to my children but I have to sugarcoat them a little bit because it’s hard to believe it happened. Just like in other cultures, my friends from Korea and Japan… They never talked about what they really knew.

Do you think that’s why you use your art to express those feelings?

Yes! It certainly wasn’t for money. I had no idea you could make money on art. That’s why I gave away so much of my work—and still do. The idea of producing it was my main goal. That became a habit and an addiction.

You started out drawing. What did you like to draw as a kid?

Airplanes. World War II airplanes, and when I reached the age of 10, planes from the Korean War. I memorized all the production, every company… experimental planes, the transition from prop to jet, even the middle area of prop-jet engines. I understood “supercharging” at a very young age.

At the same time, I suffered from dyslexia. I couldn’t sound out words. Everything seemed to flow in the wrong direction. So I created my own formulas and methods in order to get by. I couldn’t sit still and things wouldn’t stick if I wasn’t interested in them. I was never called upon in class. My teacher would talk about rocketry and early space exploration, and I knew more than she did! But I was never asked to speak about it. That was the beginning of my formal education.

I remember the day my guinea pig died—after that terrible experience and in that same year, I was denied another grade level. My twin sister went on to high school, but I couldn’t because of my grades. That was a kind of trauma. During my grade school years, I experienced negative teaching practices, such as being sent to the cloakroom. Sitting with two other students among the hats and coats hanging in the closet, I imagined them as being people. I would draw in the margins of my paper instead of doing math. And when I did the math, I began to create shapes out of long division and multiplication. They became turnips and carrots and airplanes, because I only saw the profile of things.

What was Decatur like back then?

Decatur was heaven. Everything I did in those days brought a smile to my face. I was aware of the change of the seasons: how the sun went down on Sunset Avenue, the way torrential rains would flood the streets. I made paddleboats out of rubber bands to see if I could get them across the street [Laughs]. That was my whole world.

You were also on the track team, weren’t you?

Yes, I was very fast and I could run a long time, but I never practiced. I also played football for a while. I stopped because my art teacher said I shouldn’t be playing football—I should be studying art. She had seen my secret drawings [Laughs]. Justine Bleeks was her name. She was a savior.

I was also left-handed and trying to learn music. You have to learn math to learn music, and I didn’t have a very strong math background at all. But what happened was my ear—I could memorize melodies. I could hum bebop solos at a very early age. When I moved to Peoria, it just shocked everybody. Guitarists Steve Degenford and John Miller would say, How can you remember these melodies? Because my brain shifted.

How did you get your first guitar?

There were a lot of raggedy instruments lying around. I think people came through the neighborhood and dumped them, like old pianos and stuff. I collected a lot of guitars—most of them without strings, or so warped you couldn’t play them. But they were treasures to me. I started fixing them up and playing them. If they were missing strings, I would put a wire in the right place and play them.

Who were some of your early musical influences?

That would be [jazz/blues guitarists] Barney Kessel and T-Bone Walker. I was 10 or 12 years old, and those guys definitely influenced my playing.

So you got into both music and art at a very young age. Was there ever a conflict between the two?

To me, they didn’t conflict. They were the same… like drawing and painting. I know a lot of sculptors who say, You draw? You paint?! But I never saw the difference. I see it as three-dimensional work; I think it was that dyslexic condition kicking in. When I’m forming clay, I can see the back of the piece as well as the front. I’m looking at it three-dimensionally already. With music, I can hear a note before I play it. That developed out of dyslexia and being left-handed—because everything was for right-handed people. This gave me a much broader view of how to do things. I was always formulating and devising my own way.

How did your band The Rhythm Aces come together… were they your buddies?

How did your band The Rhythm Aces come together… were they your buddies?

They were neighborhood kids. At 12 years old, I showed Howard Roberson some bass lines. His dad bought him a large ukulele and he accompanied me. And then I thought, Hey this could be a band! This was the beginning of rock n’ roll. It went all the way back to slavery—field shouts and gospel—all of that was called “rock n’ roll.” We would practice in my basement because my parents were so cool. I painted the whole basement and put [musical] notes on the wall… because I wanted to create a nightclub. That’s where we all came together and started playing.

You released a couple of vinyl records in the early sixties. How did that come about?

This was in 1960-62. [Peoria promoter] Blane Gauss sold our performances to Vee Jay Records in Chicago. Blaine would take us to these little places… like Alta, where I can still see the church where we did our recordings. We also went down to Nashville and had the opportunity to see Elvis Presley and other performers. But we never paid any attention to them, and they never paid attention to us. We’d go into the studio and make noise with Big Ron Hoffman, a big Decatur dude. He kept us safe. Going from Cairo, Illinois into the deep South, we would get stopped by the police… and he protected us. The money from the records, though, was nothing. Somebody got the money. But all Black performers went through that.

You and your band would play in Peoria pretty often. I think you ran into Richard Pryor around that time…

Yes, Richard and Chico, a guitar player, [musicians] Cecil Grubbs, Jimmy Binkley and Wild Child Gipson! This was in the early sixties at a place called Collins Corner. The owner was Bris Collins. I met Bris later on; I remember he had an old Caterpillar tractor—a big old crawler like the Holt tractors. But he was involved in running numbers, gambling, prostitution… all of that stuff happened on that corner, right up under where the [McClugage] bridge is now.

We had those tight, silky pants and were making pretty good money. I had a Chevy Corvair, one of the first ones that came out. My brother-in-law Duane Livingston and I always traveled together. He was our tenor sax player and he could play so well. We would travel to our gigs and hook up in that Chitlin Circuit. [The Chitlin Circuit was a network of performance venues for Black musicians and entertainers during the era of racial segregation.] It was just a blend of happy times.

We ran into [jazz legend] Stanley Turrentine on the Chitlin Circuit. We also ran into Bo Diddley and Ike & Tina Turner. But we couldn’t play the blues after midnight… and one day, I saw why. Because people go crazy! When they’re all liquored up and you play the blues, it brings something out in people.

And then the Beatles—those guys from England came over and brought the blues and old blues musicians back and put them right in our faces. If it wasn’t for that, the blues wouldn’t have survived.

How long did you tour with The Rhythm Aces?

Our career lasted a good strong decade. We played all the river cities… Quincy, Hannibal… that’s where we made our bread. We’d drive from Decatur to make 15 bucks a man. That was big-time! We had a Volkswagen bus, and I can tell you stories about that bus! [Laughs].

How did you meet your wife Melba?

I met her when I was a teenager. She’s from Clinton, Illinois, the most beautiful person on the earth, and she really turned me around. She was an honors student and wanted to pursue teaching as a career. She made the highest grades in the state effortlessly, because of her grandmother. Then she heard my rock n’ roll band—we’d be playing at the Elks, the A &W Tavern and the record hops. We knew that we were going to get married. We didn’t even have to say it; we just knew it. It was something I’ll never forget, because it was so righteous.

So you toured and played music as a teenager, and then you went to Millikin. What led you to continue your education at Southern Illinois University?

The fact that I flunked out of Millikin for some strange reason. This one teacher gave me an “F,” in art of all things! It didn’t make sense—I was the best in the entire school. Someone recommended a tutor to help bring my grade average up, and she brought it way up. This little white-haired white lady taught me how to diagram sentences. She had to figure out… what was my problem? I told her that everything seemed like pictures.

The dyslexic are sneaky people. We create these formulas without even knowing we’re creating them. I had ways to deal with reading backwards. And I had ways to recognize words—because of their shapes. She said, you can do this. I got to turn these visual structures into numbers; I can’t even explain it today. So I was able to transfer out of Millikin and went to Carbondale.

Southern Illinois University was a big, beautiful time in my life. I turned corners in terms of developing as a person. Melba and I had a little baby, Natalie, and later Alice came along. I thought I could dodge the draft by having another one! [Laughs]. That wasn’t the reason, but I thought it would help. I was in college and they were grabbing young Black men off the streets. All the guys I knew were drafted.

I had a hell of a band that was making money, and I hooked up with the Black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha. I met Mr. Breeland and Milton Sullivan—these were white teachers who took me in, took care of me and taught me things. I had never seen that many Black people in a college setting! It shocked me at first, but I adjusted to it. And when I did… Bam! Now I’m looking at getting my MFA.

Southern Illinois University was where it all started. But one teacher had to break the news that I could not student-teach in southern Illinois because of my race. This was hurtful for both of us. He was trying to set me up for a doctorate degree and was so saddened by the fact that I had to drive all the way to Chicago to student-teach… That wasn’t a pleasant experience.

Was there a moment that was like a political awakening for you?

The sixties hit me like a ton of bricks! I became more aware. There were radical groups on all levels on campus. I was a big part of that movement. It bothers me today to even talk about it. The National Guard occupied the campuses, and we had to reroute our trips just to get to class. There were several clashes. I took my wife to one in Champaign, and students were running away from the police and we got caught up in it. That was when they started putting flowers in the gun barrels.

What was your experience like teaching at Western?

Western Illinois in Macomb saved my life! It was a learning experience for me. As a very young teacher, it was like going to college again. I stayed with the Parkers—Sam and Becky Parker fixed their basement up for me, with a pool table and everything. I met some of the best people and I learned so much. The environment was not busy and crazy and expensive… it was a small city. I gained a lot of lasting friendships. This is why I can’t be prejudiced—I kept discovering real, soulful people.

I stayed in Macomb about 13 years. That’s where I got tenure as a professor. They gave me all kinds of wonderful things and the camaraderie among the teachers and faculty was so great. And the students, I sort of grew up with them. It was wonderful. I hung out with the townspeople; there wasn’t this big division between town and gown. Some of my best friends were farmers. Guys would come in and take my courses because they wanted to learn casting and other artmaking techniques. And they had skills!

In the mid-nineties, you started the Checkered Raven art gallery, which became the Contemporary Art Center of Peoria. Tell us how that came about.

It all started at the Murray Building. Dan Philips [Illinois Antique Center] and I rented space there, but we could never purchase the place. I had a studio and I had to grow. In order to grow, I had to go. So we strolled down here, where we are now at the Contemporary Art Center.

It was like a ghost town. There was nothing down here except Mr. Nailon [of Nailon Plumbing]. He was the “grandfather” of this empty area of Peoria. I had a huge commission about that time, so I had some money. I hooked up with [artist] Bob Emser of Eureka and we started the Checkered Raven. We wanted to create an arts environment here on the riverfront. Dan Philips got the antique center going next door, and Jon [Walker] and Steve [Rouland] bought the downstairs. We all got together and cleaned this place up. It was a mess… old coffee beans all over the place. And Bob Miller painted the place for free; he gave me just about everything I needed.

Bob [Emser], Steve Shostrom and Terry Karpowicz and I decided to start a sculpture walk on the riverfront, and that was really successful. Then Bob split. I could have sold the Checkered Raven and moved to Chicago, where I was working. But I stayed because, well, there were a lot of people who were genuinely interested in us remaining here. And that’s where William Butler came in. He rented a studio at first, but he showed interest in being [executive] director, and he’s still here. We were very successful because of William Butler.

How did you get into martial arts?

That happened around 1968. I was interested in a non-aggressive kind of martial art, due to my interest in both self-defense and the civil arts. That led me to Tai Chi. The whole idea of fighting and hitting someone, I wanted no part of that. I was introduced to this guy at Southern Illinois University, and I began to learn the various patterns. I went really deep into it… fifth-degree black belt in Taekwondo. Master Soo Kim [of Peoria] taught me a lot. He was exceptional.

Did that inform your artistic practice as well?

Oh yes, as an instructor in drawing, I couldn’t wait for my classes to begin at Western Illinois University. I couldn’t wait to do the dance that I learned in Tai Chi, but with charcoal on paper.

Let’s talk about your artwork! You’re so prolific… I don’t even know where to begin. How about Bronzeville to Harlem, since that’s now on display at the Peoria Riverfront Museum. When did you start that project?

That was about 25 years ago. I was messing around with this clump of wax in my hand. I dipped it in hot water and began to model it, and I noticed the strange and wonderful forms that were on the surface… like an Impressionist painting. So I did it again and again. These figures started growing all over the place. And I thought if I’m going to speak about [Black nationalist/political leader] Marcus Garvey and the Chicago Defender and the Great Migration, I should build a city. I should try to reflect the development of neighborhoods. So I started welding the buildings and casting figures.

I had built a foundry at Western Illinois, and Bob [Emser] and I built one in Eureka. And I started casting my ass off. So many figures! I started saying to myself, Why don’t you give these figures meaning… bring them to life? So I started naming them after people I knew, as well as some famous people from the Harlem Renaissance. All of a sudden, the entire thing woke up and became a form of life itself. It was an explosion of energy that took place, sort of guided by social issues. An explosion of expression!

I say “we” because I had a crew—including Vicki Glover, Pat Keck, Marge White, Everett Renno and Janet Jackson. My right-hand person is Joy Kessler, as well as my daughter Alice. Joy’s family and her husband Steve were in on this, too. We had a society. It brought people together.

I did another show called Julieanne’s Garden. It was like a larger version of the type of activity that I put into Bronzeville to Harlem. It was a different type of expression about Black life in our society. The figures became expressionistic, stylized and included narratives as an integral part of the work.

You also have created many likenesses of famous people: Richard Pryor, Miles Davis, Fred Hampton…

We started doing large commissions, and that is continuing big-time. Things have just exploded over the last decade.

Let’s talk about passing your talents on to your daughters. Was there a conscious effort to raise your children in a rich cultural and artistic environment?

We made an effort to make sure they become knowledgeable about a lot of things, without pushing it on them. It was natural. We had a lot of plants. Have you heard about my reptile phase? There were many terrariums and aquariums in our home, housing a variety of living things I was interested in. I had some Mexican iguanas and green emerald iguanas. When I acquired a rather large tegu lizard, my interest began to wane, and especially when I began to raise alligators.

Natalie began to draw first because she’s the oldest. She would come right behind me and draw things. When Alice began to take on writing and the visual arts, I knew they both had something special. Just recently they both took on art as a true profession. They see their dad is still doing this, and they saw the trials and tribulations I went through. Now they pick up anything—a pencil, a camera—and it turns to gold. It’s right on, every time. I’m very proud.

So much of your work is grounded in historical and social issues. What do you believe is the artist’s role in society?

Well, there are people who are in the profession and it’s easy for them. There are the privileged artists who can spend their time exploring and dealing with form or subject matter that is accepted, and it brings fame and fortune. Then there are the artists who have a need to express social issues. I tend to admire them because they create art to save humanity, or as commentary—art that will make us better people. I’m still in that place.

I can’t afford to do super-abstract stuff or pretty art—still lifes and landscapes. Many artists I know, their work doesn’t say anything. Give me someone like Ernie Barnes or Charles White. Look at Pablo Picasso’s work, Guernica. Look at Goya. Who was Edith Piaf? Look at her life, listen to her voice, listen to what she sings about. Ennio Morricone, who created all these beautiful compositions and film scores. Listen to him a little bit closer—just stop whatever you’re doing and listen. Or the work of Janis Mars Wunderlich. That’s the side I’m on. That’s what really motivates me. I don’t care if I starve to death; I’ll always make art.

What are you most proud of? Is there a specific work, or something more general?

I don’t sell much. A lot of people think, boy, he makes a lot of money. I don’t make a lot of money. I have an inventory you wouldn’t believe… I get a lot of rejections. Fifty percent of my existence as an artist is rejections. What am I proud of? I’m proud of the motivation. I’m proud of the fact that I still have principles. I still feel the need to make something happen. And I still get pleasure from it. PM