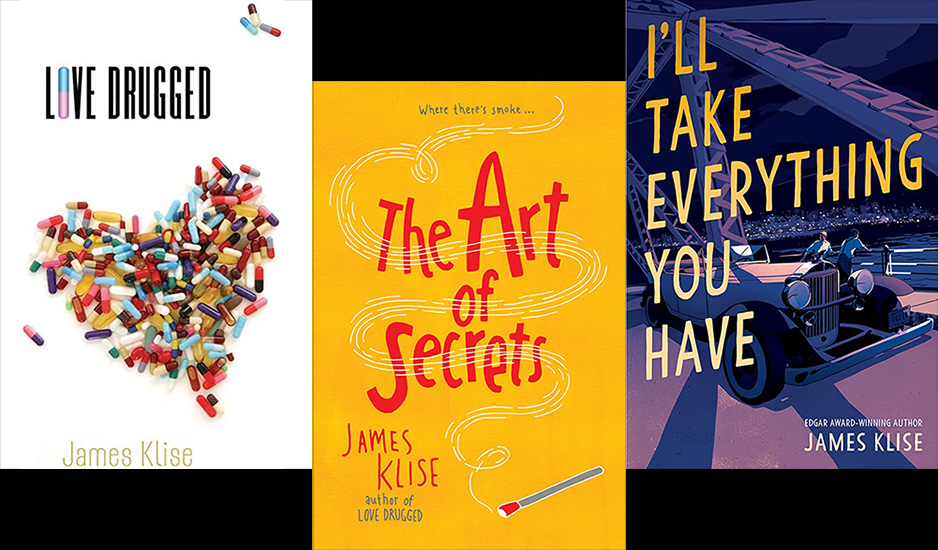

James Klise is a Peoria native and author of the Edgar Award-winning book The Art of Secrets and of Love Drugged, which received a Stonewall Book Award. His latest, I’ll Take Everything You Have, was published by Algonquin Young Readers in February of this year. He recently participated in this email Q&A with the Peoria Public Library’s Jennifer Davis (JD).

James Klise is a Peoria native and author of the Edgar Award-winning book The Art of Secrets and of Love Drugged, which received a Stonewall Book Award. His latest, I’ll Take Everything You Have, was published by Algonquin Young Readers in February of this year. He recently participated in this email Q&A with the Peoria Public Library’s Jennifer Davis (JD).

JD: In the near decade since your “snub” happened in Kansas, have you had other experiences of censorship, either as an author or school librarian?

James Klise (JK): Yes, in 2021, Love Drugged was included on lists for review and removal in both Texas and Virginia. Overt challenges like these are relatively new, but spreading fast. The more ordinary experience is that books like mine simply don’t get purchased by certain community libraries and schools, even if they become bestsellers or win some recognition from ALA.

In those communities, in order to include LGBTQIA+ texts in your classrooms, you need to be an especially brave and generous educator. You risk losing your job. In contrast, I’ve managed a library in Chicago for 20 years. It’s a public high school library in a diverse community, including many religiously conservative families, and I’ve never had a parent object to a book.

The way we do it, if students or parents don’t like a book, they don’t borrow it. Easy. That way it’s waiting there, available for someone who does want to read it.

JD: Did you, by chance, keep in touch with that librarian in Kansas, and if so, do you know what’s going on there given the nationwide surge in book challenges/bannings?

JK: I haven’t heard from her, although when I wrote the essay for the paper, I shared it with her first to make sure I represented her point of view accurately. She was extremely gracious about it. That was a stressful situation for her to be in.

I’ve read many stories, of course, about the newer book challenges in Kansas and elsewhere. When librarians get together now, that’s what we talk about. The situation is scary. The notion that certain people in government want to control which books find their way into classrooms and libraries, based on politics …

I mean, what country is this again?

JD: Growing up in Peoria, what was your life like?

JK: I’m the youngest of six. It must have been a good childhood for writers, given that my sisters write and publish too. And my sister Sarah has illustrated dozens of books. Our parents, Tom and Marjorie Klise, deserve the credit. We never had cable TV, but we had a desk in the hall crammed with art supplies. We had a closet filled with costumes. And we lived on a street with lots of kids. At that time, Moss Avenue had quite a few big families, five (or) more kids each.

My sisters and I loved going to the library. For one thing, the library was air-conditioned, unlike our house. Plus, visiting the library gave us choices. Kids in the 1970s didn’t have many choices. Back then, nobody ever asked kids what they wanted for dinner.

JD: You were a closeted gay teen.

JK: Closeted or clueless? It was the ‘80s. In some ways, it was easier for us back then because of our utter cluelessness. Two of my best friends grew up to be gay men, too. But in high school, it was never discussed. It’s unbelievable in retrospect, but we’d sit around talking about musicals and Diana Ross, and we watched the VHS of Thoroughly Modern Millie over and over, and we never, never — not even once — spoke about it.

I figured I was a late bloomer. It’s difficult for young people now to grasp what it was like to live with so few queer role models. The drag queens on (the TV talk show) Donahue — they were fabulous, but it was a limited view, to say the least.

JD: What does it feel like to write books that can reach a child who feels “excluded and invisible”? In other words, do you have stories from readers you’ve touched?

JK: The wonderful thing about writing books for teens is that they write back. I’ve received lots of emails from readers in small towns — especially with the first book, because in 2010 there were so few titles available to LGBTQIA+ readers. Since then, the literary landscape has completely changed. I can’t keep up with all the new books every year. It’s amazing.

My new novel looks back to the summer of 1934, which was a time when gay and lesbian people were mostly invisible and excluded from society at large. The story dramatizes the thrill of that invisibility, but also the real danger.

At this point, the work I do in my school library — just being openly gay and working hard to make the space as inclusive and welcoming as possible — that’s probably the most important way I make all teens feel included and seen.

JD: Conversely, how do you feel having others criticize your book — as you said, not for the quality or content — but just because it’s LGBTQIA+?

JK: Fortunately, that doesn’t happen too much, except maybe on Goodreads. If you mean the groups who are challenging and removing books with LGBTQIA+ content, I literally don’t understand it.

As you might guess, I have strong opinions about books. You know what I do when I see a book that doesn’t work for me? Either for myself or for my library? I opt for something else. I don’t make choices for other libraries or for families.

This is America. If people want to keep certain books out of schools based on their personal religious beliefs, then my personal belief is they should operate private schools. Can you imagine the motto? “Fully committed to the education of some students!”