As a crusading journalist, Barb Drake made more than headlines: She helped shape the Peoria we know today.

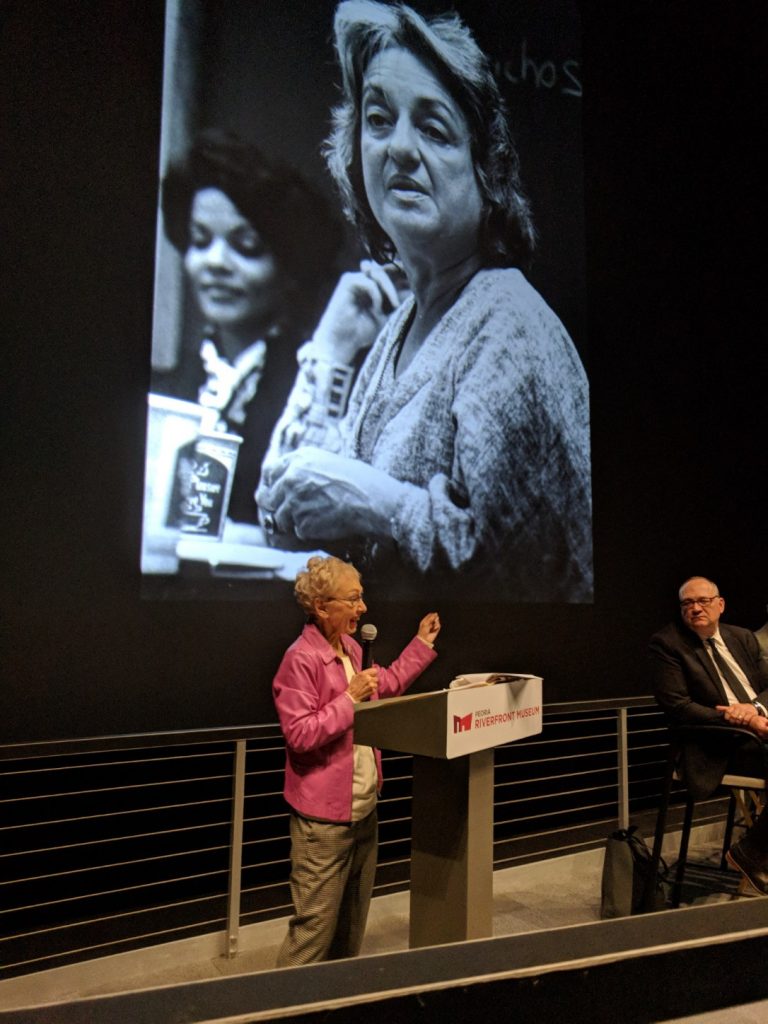

Barb Drake relishes discussing her interview with feminist icon Betty Friedan.

Please.

If anybody is a feminist icon, it is journalist Barb Proctor Mantz Drake. Her impact may be more local than global, but her tale of tenacity and intelligence is every bit as riveting. More on that later.

A Lifetime of Overcoming

Barely five feet tall and 100 pounds—even when toting a reporter’s notebook and research tomes—Barb Drake can dominate any room by sheer will. She earned it.

Her parents were radio personalities in Dubuque, Iowa, and Barb’s birth was announced on air. Her biological father, Hal Pearce, died when she was a baby. She was 8 when mother June was remarried to fellow station employee Paul Proctor, whom Drake thinks of as her father. They moved to Peoria in 1955 so he could work at WEEK-TV. Brother Doug joined the family in 1957.

Paul was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) when Drake was midway through her four years at Woodruff High School. When he could no longer work, June supported the family on a teacher’s aide salary. Money was tight. Barb has always touted alma mater Bradley University—she graduated Class of ’67 and is a member of the Centurion Society in recognition of extraordinary achievement—for making it possible to get her degree.

In her 20s, then-Barb Mantz battled Bell’s palsy, which manifested when she was pregnant with her son, JB. Her husband died when JB was 4 years old, and she was a single mother throughout her 30s. At 40, she married Bernie Drake, likewise widowed, who had his own teenaged sons, Todd and Brent. In their 50s, the Drakes were running two households as Bernie commuted from his job with Komatsu in the Chicago area. While there, he suffered a heart attack while taking a stress test on Valentine’s Day. Into her 60s, Barb helped care for brother Doug, who was disabled by lupus and died at 56.

Now 77, Drake herself has dodged death more than once. That includes two serious cycling accidents which put her in the hospital with a combination of collapsed lung, broken collarbone, smashed elbow, broken arm and back injuries.

The woman literally was hit by a bus and, again, battled back.

“The bus driver was making an illegal turn,” she clarifies, making her usual larger point. “People always want to think it’s the bike’s fault.”

Banned from the bike by family, she remains committed to fitness, walking the Rock Island Trail she once championed as an opinion page editor. Despite ongoing therapy and back treatments, she continues to add exotic destinations to the long list of places she’s traveled to with Bernie: Europe, Russia, Scotland, China, Australia and New Zealand, South Africa, Southeast Asia and, this October, Egypt.

Perhaps most remarkable, over nearly 50 years of friendship, Barb Drake has been sad sometimes, but never self-pitying. She prefers to focus on facts—like a laser.

Public Impact

Once upon a time, journalism made a difference and Barb Proctor wanted in.

Not only did she publish her own neighborhood newspaper when she was 6 or 7 years old—5 cents!—she became editor of the Woodruff Warrior student newspaper and, later, held the same position at the Bradley Scout. While she could have used one of the Journal Star scholarship/internships awarded by the newspaper annually, she was ineligible at the time: She was female.

“A few years later, I was sitting on the committee that gave the scholarships,” she said, with no small satisfaction. “That’s emblematic of how things changed.”

Drake was not the first female reporter or editor at the local newspaper of record. But once hired, she kept pushing the glass ceiling. Hard.

As consumer affairs reporter, she did an exposé of local car dealers’ pricing that caused them to pull their advertising en masse—requiring the (male) editors to apologize. As assistant city editor, her unrelenting questions and requests for improvement may have driven some reporters to the verge of drink. As assistant and then senior editorial page editor—the latter from 1990-2005—she advocated for Peoria, armed with facts and context and endless curiosity.

Former Illinois Gov. Jim Edgar recalls “a bunch of crusty old men” on the editorial board when he first ran for Illinois Secretary of State. In his view, they didn’t like Springfield. Their concerns were Peoria-only provincialism. That changed by the time he opted for the top job.

“It was quite a transition when you went from them to when Barb was running the show,” he said.

Edgar called Drake the overall best-informed editor in the state. That included Chicago’s newspapers, which tended to have their own us-first attitudes.

“Barb knew what affected Peoria, but she also knew what was going on in Chicago and how it played in the rest of the state,” he said. “That was a breath of fresh air.”

Back then, politicians regularly visited newspapers to advance their agendas and plead their causes, especially around election time. Edgar said he always braced himself for a challenge at One News Plaza. In a two-party system, independent journalistic checks and balances made everything better, himself included, he said. Peoria was “very fortunate” to have Barb Drake.

“I think it kept me and a lot of other people in the straight and narrow… You didn’t just want editorials. You wanted the endorsement,” said Edgar, recalling the polling places littered with newspaper clippings that voters used for guidance on Election Day.

Drake and her fellow editors took that obligation seriously. They spent months vetting candidates for readers who didn’t have time to investigate for themselves. They have boxes of awards to show for it.

More importantly, Drake cites the editorial crusades as producing the biggest impact of her life’s work. For example, the Drake-led Journal Star Opinion Page fought to retain local mass transit service after she spent an entire day riding buses around Peoria soaking up the real-life experience of other riders and collecting their stories of need.

“When 80,000 subscribers read the paper—I don’t think this is bragging or overstated—I think we had a positive impact,” Drake said.

BU sorority sister and lifelong friend Joan Krupa agrees. As a Republican who served two terms on the Peoria County Board and briefly in the state Legislature, the two did not always agree. If anything, being a friend of the editor caused said editor to ask tougher questions. Krupa said she was “a nervous wreck” whenever she talked to the editorial board, but always felt that Drake dug deep to get to and tell what she saw as the truth.

“To me, she epitomized what an editor should be doing,” Krupa said.

As an educator, counselor and community volunteer, Krupa was equally accomplished. They came together for a singular public health crusade: the Heartland Clinic.

When Krupa became CEO/director in the 1990s, the Heartland Free Clinic was $40,000 in the red and its mostly volunteer staff served about 800 patients. Krupa took note of an editorial Drake had written about federally funded community health centers. By the time Krupa retired six years later to try politics, what’s now Heartland Health Services was federally qualified and had a balanced budget and 18,000 patients.

“This was a great, great gift to the city that Barb provided with her investigative abilities,” Krupa said.

The power of the press was key to getting multiple community initiatives over the top, Krupa said. Over the years, the newspaper took a leadership role in advocating for multiple causes: for confronting the local epidemic of teenage pregnancy, for riverfront development, for the rescue of the county nursing home, for the extension of a now-popular recreation trail, for a bigger and better library system, etc. In many ways, central Illinois looks the way it does today in no small part because of those efforts, not least of which on behalf of the Peoria Riverfront Museum.

Not surprisingly, PRM President/CEO John Morris agrees, enthusiastically.

“She saw the power in having a multi-disciplinary museum,” he said.

As an example, he mentions a Wisconsin family who drove down to celebrate PRM’s 10th anniversary free admission day in October as an example of the long-term fruit of the 147 museum editorials that Drake either assigned, wrote or collaborated on.

“She never gave up. She planted the seed and planted it and planted it—147 seeds—hoping one would grow,” Morris said.

It did. And Barb and Bernie Drake, both of whom remain actively engaged in the community as volunteers—at Bradley’s OLLI program, at First Baptist Church in Peoria, etc.—were awarded the museum’s highest honor, the James Smithson Award, in 2020.

“I think it is not at all an exaggeration to say that without Barb’s tenacity that we should have a world-class museum, it would not have happened,” Morris said.

Taking root, taking charge

One “seed” still blooming was the commitment by PJS and WTVP-Channel 47 to record the stories of remarkable Peorians before they were gone—sci-fi writer Philip Jose Farmer, Race for the Cure founder Nancy Brinker… and, of course, Betty Friedan.

Ah yes, about Friedan.

Drake doesn’t always tell this part of the story. After weeks of finessing—full disclosure, I was the newspaper’s project manager for the Legacy series—Drake and a film crew were slated for an interview at Friedan’s Washington, D.C. home. Granted, a mess of lights and cords and strangers is intrusive. But minutes into the discussion, the phone rang and kept ringing. Friedan lost it. She shrieked that if no one had the courtesy to answer the phone, the interview was over: Everybody out.

Thinking fast, Drake explained to Friedan that her comments were so riveting that no one had noticed the ringing phone. (Roll eyes here.) Mollified, Friedan agreed to continue. The interview was a success.

There was indeed a remarkable woman worth celebrating in that room.