On May 1, 1973, three gunmen busted into St. Cecilia’s Catholic Grade School and took a classroom of 5th graders hostage

On May 1, 1973, 10-year-old John Ardis raised his hand at St. Cecilia’s Catholic Grade School.

He wasn’t trying to ask or answer a question. He was trying to save his classmates’ lives.

The fifth-grader raised his hand to volunteer as a hostage for one of three gunmen who had seized the school. Minutes later, a hail of bullets would make Peoria the focus of newscasts and newspapers nationwide, a terrified country stunned at the then-unheard-of scenario of gunplay at a school.

“Fifty years ago, this stuff wasn’t on TV, it wasn’t in the movies, it certainly wasn’t happening in real life at the schools,” says Ardis, now 60 and living outside Chicago.

A day unlike any other

Located in the middle of Peoria, St. Cecilia’s had 80 students in grades five through eight in the 1972-73 school year. One of the fifth-graders was John Ardis, son of then-Councilman James Ardis. Three siblings (including Jim Ardis, later the four-term mayor of Peoria) also attended the school.

Because of declining enrollment, St. Cecilia’s already was slated for closure after that spring semester. But the school would not fade quietly, thanks to Melvin Burch.

The 25-year-old Peorian had returned from Vietnam with a Purple Heart and an embittered attitude, friends would later say. He looked around and saw a country in need of change. He wanted to shake things up.

He made his move just after 2 p.m. on that May 1 exactly 50 years ago. He and three friends held up Brown’s Sporting Goods, just south of Downtown. They snatched two rifles and five handguns, plus boxes of ammunition.

One of the robbers dashed off. Burch led the other two to St. Cecilia’s.

“Suddenly, some men blasted into the classroom and started ordering us around,” John Ardis recalled. “And they were armed. We didn’t know what to think. They basically said they were taking over the school and taking us hostage.”

Burch yelled that he had enough explosives to blow up the school. The gunmen forced 30 fifth-graders, including John Ardis, into a basement cafeteria. At first, students were too stunned to do anything except follow orders to lie on the floor.

“We were all just kind of adapting and trying to process what was going on,” Ardis said. “This kind of thing was unheard-of back in 1973 — and fortunately was way less common than it is today.”

Teachers cooly told the kids to stay calm. They did, until the gunman started firing out the basement windows toward the police officers who had surrounded the building.

“I was terrified,” John Ardis said. “It absolutely was surreal.”

Some students began to sob. Many prayed. None understood the gunman’s goals. Burch sounded chaotic and unclear.

“They basically said they were there on some sort of mission,” Ardis said. “They were fine if they died. They specifically told us that for every one of (them) that was killed, they would kill 10 of us.”

Then, Burch announced a new plan.

Seeking a volunteer

“The main guy, Burch, said he wanted a couple volunteers to take their demands to police or a radio station. I can’t remember what it was,” Ardis said.

‘I felt terrified that some of my classmates were going to get harmed’ — John Ardis

Burch asked for a volunteer to go outside as a hostage. Several kids raised their hands, including John Ardis. Why did he volunteer?

“I don’t know,” he said quietly. “I’ve gone back and forth over time. I think I thought they were going to hurt my classmates. It was just like, ‘We need to do what they say or someone is going to get hurt.’ And I think that was really it. It was just as simple as, ‘Somebody’s got to do this.’”

About 2:50 p.m., Burch headed out a school door with the boy.

“He tells me not to try to do anything funny,” Ardis recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t plan on it. I’m 10 years old.’”

Outside, the boy noticed a crowd of about 5,000 onlookers, including parents of schoolchildren, along with legions of police officers.

“Oh my gosh,” Ardis’ screamed to himself. “There’s guns everywhere.”

‘I’ve come to die!’

He wasn’t sure what to expect from Burch, who kept his right hand on Ardis and his left hand on the gun. Firing a shot into the air, he yelled, “I’ve come to die!”

He did.

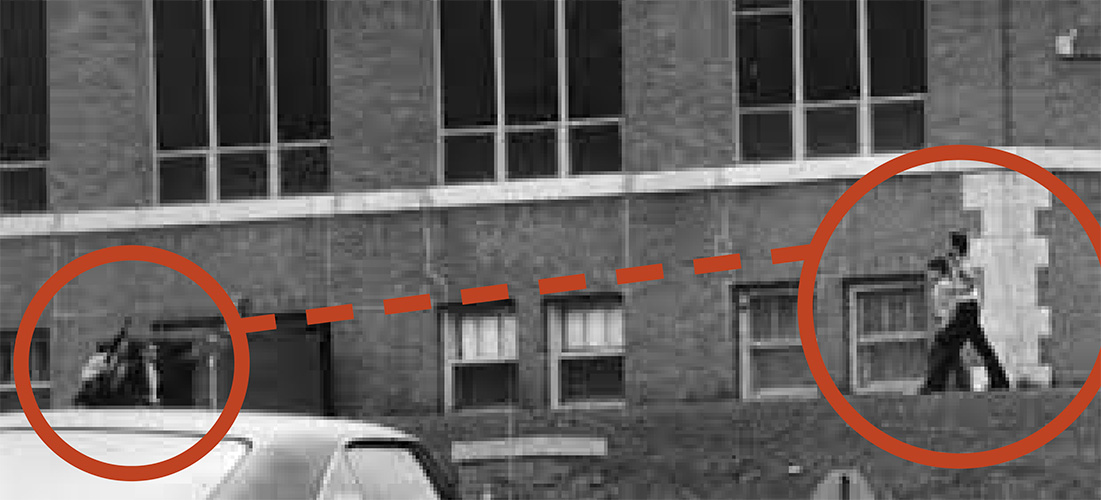

While leading Ardis forward, Burch stumbled just slightly, allowing a sliver of daylight between him and the boy.

“It was enough for one of the snipers to take him out,” Ardis said.

As Burch fell, Ardis bolted away. A fusillade of police gunfire rained down on the prone Burch. Officers grabbed Ardis and led him away from danger. He soon was reunited with his mom, then his dad.

Police continued to crouch around the school, as the other two gunmen remained inside with the other students.

“I was scared for a time because they said for every one of them who got killed, 10 of us would get killed,” Ardis said. “Well, one of them just got killed right next to me. So I was thinking, ‘I feel fortunate.’ But I felt terrified that some of my classmates were going to get harmed.”

Alas, about 90 minutes after the standoff began, the other two gunmen surrendered, with no further casualties.

Sudden celebrity

Afterward, newspaper headlines trumpeted the story nationwide, triggering letters to Ardis from well-wishers around the globe. He received commendations from Illinois Gov. Dan Walker and President Richard Nixon. And the 10-year-old boy felt overwhelmed by what he now calls a “circus.”

“It was like it wasn’t real,” he said, still sounding slightly confused decades later. “It was too weird. It was too bizarre that all of this attention was suddenly going on.”

For a week or two, Ardis had occasional nightmares, prompting him to sleep with a light on. But things soon fell into a familiar rhythm.

“Life just kinda went on,” he said. “It just started to fade into memory.”

Ardis, who experienced no discernible emotional drag from the standoff, went on to graduate from the University of Illinois. Now retired, he worked for more than 30 years in marketing and advertising. A half-century after the standoff, he commends the poise of teachers and police, who at the time had no playbook or training regarding active shooters.

“They were just going off their instincts and skills,” he said. “They did just an unbelievable job.”

He still marvels at the attention he got from across the globe, something he doubts would happen today.

“They came flooding in from everywhere,” Ardis said. “It was amazing how far it reached. But then again, no one had hardly heard of a hostage situation” in “a grade school full of little kids.

“It was unprecedented.”