Federal Judge James Shadid’s story is America’s story, and he’s never forgotten where he came from

Amid many professional and civic duties, U.S. District Court Judge James E. Shadid cherishes naturalization ceremonies.

“They’re very important to me,” he says solemnly.

When Shadid swears in new citizens, he revels in a collective and historical thrum of promise and hope, harkening back 90-some years when his forebears came to America.

“My grandparents paved the way,” said Shadid, 65, of Peoria. “They could not have imagined what their children and grandchildren would become. But they did imagine we could do our part to make this a better country, for ourselves and for others.”

Their attitude, shared over years in Shadid’s youth, echoes as the core of Shadid’s worldview. Never forget where you’ve been, and always help others get where they’re going.

“None of us makes it alone in life,” he said. “Someone opens the door for us. Someone mentions our name to someone else. So, we should do the same.”

As for Shadid, one of the 2023 Class of Peoria Magazine Legends, the dynamic has recurred in his life many times.

It all starts with family

His paternal grandparents, Mifla and Adeedi Shadid, came to the United States from Lebanon, as did maternal grandfather Harry Unes. So did the family of maternal grandmother Sarah Unes, who was born in America. The family believed in hard work and community vision.

“To be part of America, you need to put yourself in a position to not only support yourself but to help others,” Shadid said.

Shadid and younger brother George — better known as Georgie — grew up in central Peoria with parents Lorraine and George P. Shadid. The latter, later a Peoria County sheriff and state senator, wore a Peoria policeman’s blue. He and his fellow officers brimmed with a workaday attitude that helped form a bridge between the police and public.

“As a boy, I looked up to a number of the police officers Dad worked with,” Shadid said. “They were good, solid people who treated people right and, as a result, had good reputations in the community.”

For example, as president of the police union, the elder Shadid would sponsor movie matinees for local boys and girls.

“It was just a way to engage young people and make them realize police officers can be a friend,” said Shadid. “Dad was always interested in giving people opportunities.”

Diamonds are forever

Aside from law enforcement, Shadid’s father, who died in 2018, fostered another avocation in his boys: baseball. After work, Officer Shadid would spend countless hours with bats, mitts and his sons.

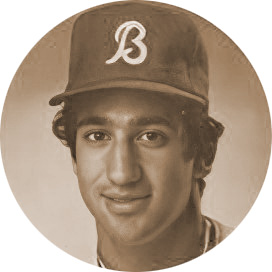

At Peoria High School, Shadid played football, basketball and baseball. Though a decent athlete, he did not foresee college athletics in his future. So, planning to attend Bradley University, he was floored when Braves baseball coach Chuck Buescher asked if Shadid might want to join the team.

Shadid later found out the offer came in the wake of a good word to Buescher from Manual High School baseball coach Ed Stonebock. Though never Shadid’s coach, Stonebock told Buescher that the teen had shown speed on the field and could develop into a better ballplayer.

Shadid made the most of the BU baseball opportunity. After a freshman year as a shortstop, he taught himself to play outfield, using his speed to chase down flyballs. He also learned to switch-hit, for an edge at the plate.

In his sophomore year, he set the Bradley single-season record for steals, at 30. The mark still stands, as does his career total of 85. Such daring prompted Bradley to tout him in publicity materials as “Mr. Excitement.” But Buescher valued him for more than his baseball skills.

In his sophomore year, he set the Bradley single-season record for steals, at 30. The mark still stands, as does his career total of 85. Such daring prompted Bradley to tout him in publicity materials as “Mr. Excitement.” But Buescher valued him for more than his baseball skills.

“Everybody liked him and looked up to him,” said Buescher, 78. “Jim always set a good example. He played hard. He was one of the first at practice and one of the last to leave.

“And he never complained.”

From dugouts to defense work

Though undrafted in college, Shadid said he knew his career trajectory: “I was totally going to be a major-league ballplayer.”

Graduating in 1979 with a political science degree, he signed with the San Francisco Giants. But after just one long summer rattling around the minor leagues, he realized he needed to reset his dream outside a ballpark.

‘He was always focused on doing the right thing’ — Attorney Ron Hamm

So, mindful of his respect for law enforcement, he decided to study law. He graduated from John Marshall Law School in Chicago in 1983, returning to Peoria as a defense attorney. Early in his practice, he bent the ear of renowned litigator Ron Hamm.

“I started showing up at Hamm’s office to grab coffee and pick his brain,” Shadid said. “We ended up co-counsel on many cases. His style of lawyering was very successful in front of juries: direct, honest and to the point, with a disarming genuineness.”

The same kind of measured, collected approach served Shadid well as an attorney, Hamm said.

“He’s a very, very likeable guy,” said Hamm, 81. “He doesn’t shoot from the hip. He was always focused on doing the right thing for his clients.”

Building a brood, chairing a courtroom

Meantime, in 1984 Shadid wed Jane Kelly. They raised three children: Jim, Joe and Maggie. As with his father before him, Shadid worked hard at his job, but made sure to keep a focus on his family.

In 2001, he was appointed to the bench of the 10th Judicial Circuit, which includes Peoria, Tazewell, Marshall, Putnam and Stark counties, then won two retention elections. His cases included brutal crimes. Among multiple killers in his courtroom, the most notorious was Larry Bright, who murdered eight women in a crime spree that shook the Peoria area.

But not every docket turned dark. Shadid, who has a wry and understated sense of humor, always has appreciated light moments.

One day, amid a crowded courtroom of endless pretrial hearings, Shadid was repeatedly interrupted by random outbursts from Willie York, the flamboyant Peoria vagrant who over decades would commit a misdemeanor early every winter to earn a jail stint until the weather warmed.

Exasperated, Shadid peered at York and barked, “Willie! If you don’t pipe down, I’m going to release you from jail!”

At that, York turned silent.

A president calls

In 2010, when a judgeship opened in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of Illinois, Shadid was nominated for appointment by President Barack Obama. The next year, he won confirmation by the U.S. Senate. Shadid still struggles to find the words to describe the experience.

“It was totally humbling,” he quietly said.

A high point happened behind the scenes, when the president met in the Oval Office with Shadid, his wife, kids and parents. The elder Shadid and the president talked and laughed about their shared time in the Illinois Senate.

“That was really special,” Shadid said.

Shadid, who served as the district’s chief judge from 2012 to 2019, remains on the federal bench in Peoria. He has observed an intriguing swirl of legal issues. Some have been as serious as the lengthy kidnap and murder trial of Brendt Christensen, which garnered international attention. Others have been as lighthearted as a case last year accusing Kellogg’s of defrauding customers by selling frosted chocolate fudge Pop-Tarts that lacked key fudge ingredients. The plaintiff lost.

As Shadid said, “It’s all very interesting, the variety of cases that come before you.”

Integrity matters

Shadid frets about judicial integrity across his profession, mostly regarding judges more focused on personal and political agendas than strictly following the law.

“I think (the bench’s reputation) is really fragile right now,” Shadid said. “And it really concerns me.”

Though Shadid essentially could stay on the federal bench as long as he would like, he says he is unsure of his next steps.

“I don’t know exactly what the future holds for me,” he said. “I am only 65. But I do recognize that there comes a time when we must all move on and make room and opportunity for the next generation.”

Away from court, Shadid has served with numerous civic organizations, included Boys & Girls Club of Greater Peoria and the Bradley University Board of Trustees. But even if were to hang up his robe, he probably would stay close to the profession, such as serving as a speaker or educator advocating judicial integrity.

“I have great respect for the federal judiciary,” he said. “And even if I am not judging, I would like to have a role in it (via) … anything that might help maintain and/or restore the trust and confidence of the people.”