When federal officials decided 85 years ago to build four state-of-the-art research laboratories, three ended up in or near big cities close to the coastline: New Orleans. Suburban Philadelphia. Suburban San Francisco.

And the fourth?

Peoria.

How did we beat 240 other cities for this plum – today’s Ag Lab – and get it built here rather than by a major rail hub, port or population center?

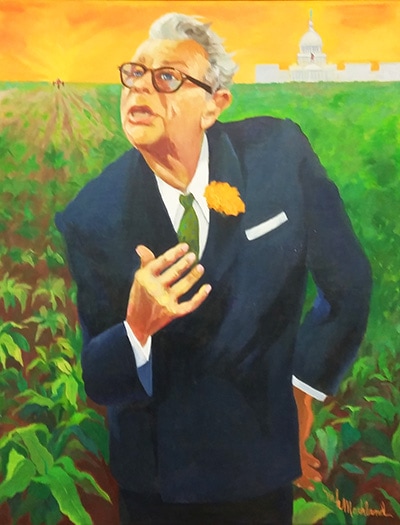

Call it a right-place, right-time intersection of what one Peoria newspaper called “political pressure” alongside community activism. This is the tale of the political muscle flexed by then-Rep. Everett McKinley Dirksen.

Despite being in office only five years, the Pekin congressman had built an across-the-aisle relationship with then-Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace, had been an advocate for research done at the lab, and had a seat on the committee that steered the construction funds.

In his autobiography, Dirksen wrote that among Franklin Roosevelt’s cabinet members, he was “probably closest” to Wallace because the latter’s department was most critical to his Illinois district’s interests, including what to do with enormous crop surpluses that were hurting farm prices. Wallace later praised Dirksen for his dedication to agriculture issues.

While Dirksen was highly critical of crop control and quota policies, documents show he was an early proponent of using research to find uses for surplus agricultural goods – a key goal behind establishing the laboratories in farm legislation in 1938. He’d pushed for more federal funds to research “alky gas” for cars, the precursor to today’s ethanol and biofuels.

“With the creation of a huge laboratory in Peoria, in the very heart of the corn belt and in close proximity to the world’s finest commercial distilleries, it is expected that alcohol gasoline will receive increased attention,” Dirksen told the Peoria Journal-Transcript at the close of 1938.

In his first few years in Congress, Dirksen proved himself a workhorse, ultimately winning a prime spot on the House Appropriations Committee. Just a year before the labs were created, he landed a spot on the panel’s agriculture subcommittee, which he’d already used to secure more funds for ethanol research. He told scientists at the lab in the late 1940s it was a “rather enviable position” to be in for steering money to the project.

Newspaper records from the time indicate Dirksen’s role – alongside Illinois’ at-large Rep. E.V. Champion, a Peorian – in campaigning for Peoria as the lab’s home. It was Dirksen who sent a telegram to Journal-Transcript publisher Carl Slane the morning of Dec. 14, 1938, to inform him of the victory.

In a separate letter that same day to wife Louella and daughter Joy, he confided that he met with Wallace days before and told him, “We must have that laboratory.” He described the news as “a real Xmas present” that would drive employment and home construction in Peoria.

Dirksen’s was also among the few speeches at the laying of the cornerstone for the lab in October 1939, which was broadcast to a nationwide audience.

Even with all those advantages, it helped to have a legitimate case for bringing the lab here.

The Peoria Association of Commerce set up a committee that crafted a 500-page proposal showing why Peoria should win out over nearby competitors such as Urbana, Danville and Decatur. Bradley Polytechnic Institute pledged to donate land from Lydia Moss Bradley’s estate for the site.

The Peoria-Pekin region touted itself as “the logical cross-roads of farm production, industrial utilization, central location and transportation facilities,” according to the association. That meant links to four distilleries, four canneries, three breweries, three feed manufacturers, two mills, three malt syrup makers, one paper manufacturer, a vinegar producer, a broom-and-brush company, a corn product refinery, a yeast plant, a chemical-and-solvent plant, a drug-and-insecticide company, two dry ice plants, six packinghouses and 14 dairies.

As we know today, of course, the Ag Lab was no mere “bridge to nowhere” pork project. Consequential discoveries started with the mass-production of penicillin during World War II.

Dirksen would go on to help secure funding for an expansion of the lab in the 1960s, and successors to his House seat would look out for the lab’s interests. Rep. Bob Michel resisted proposals by President Jimmy Carter to slash funding for the site. Years later, when President Donald Trump called to eliminate funds for the lab, Reps. Cheri Bustos and Darin LaHood and Sen. Dick Durbin would come together on a bipartisan basis to keep the lab funded and then to push for expanded research space for climate-resilient crops.

Eighty-two years after opening, the lab’s staff of about 250 continues its research on projects affecting the wider world, from biofuels to plant derivatives that reduce cholesterol. A relatively recent point of emphasis is the development of crops that are more resilient to the effects of global climate change.