Today’s history lesson: Once upon a time, Peoria found the ‘recipe for getting things done’ to ‘get the city standing tall’

Of all the redevelopment blueprints commissioned by the City of Peoria over the last half century, one stands alone as arguably the most ambitious and, in retrospect, the most successfully implemented of them all.

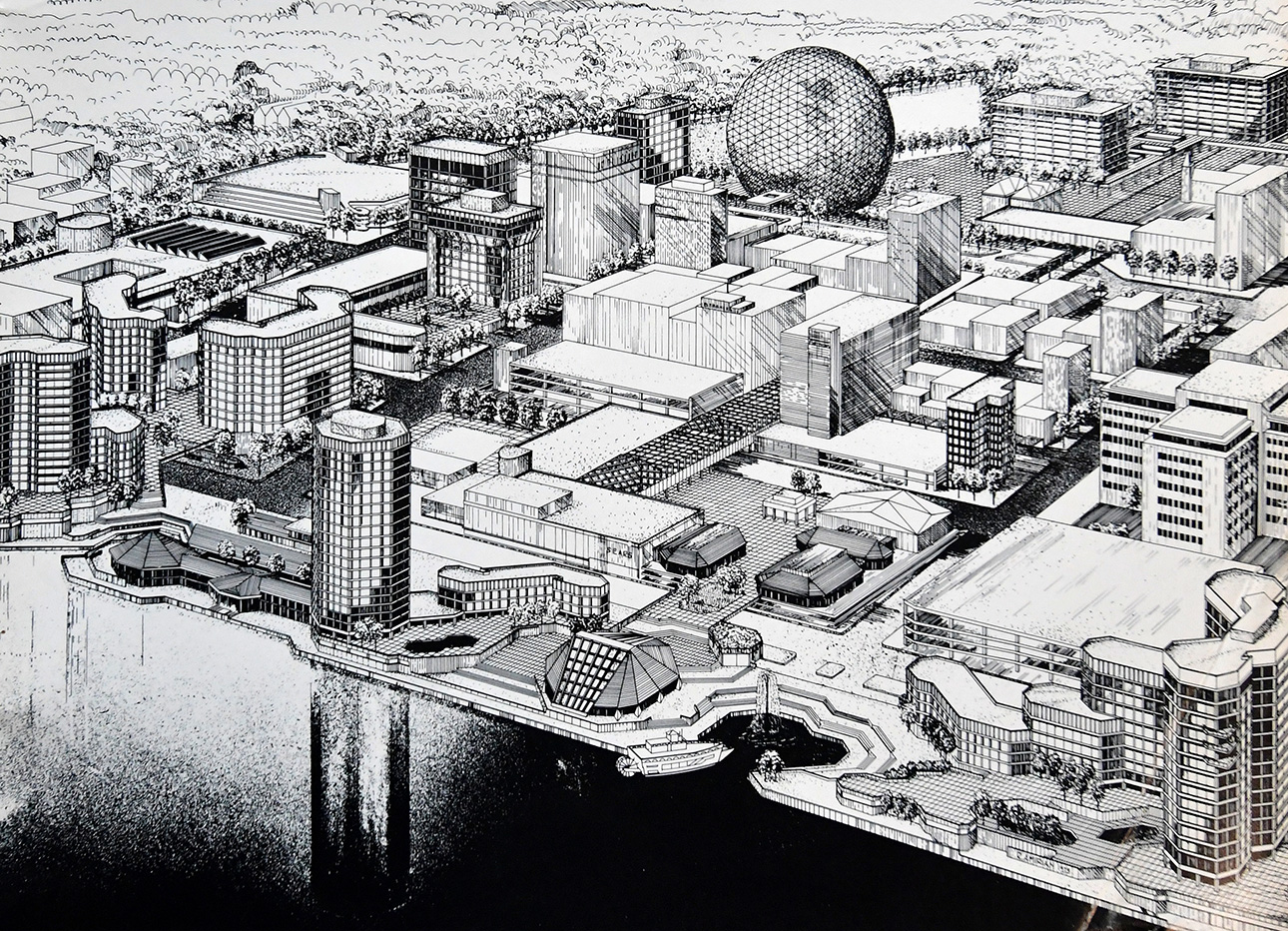

Downtown Peoria looks the way it does today, its big-city feel unique throughout all of downstate Illinois, because of the Demetriou Plan.

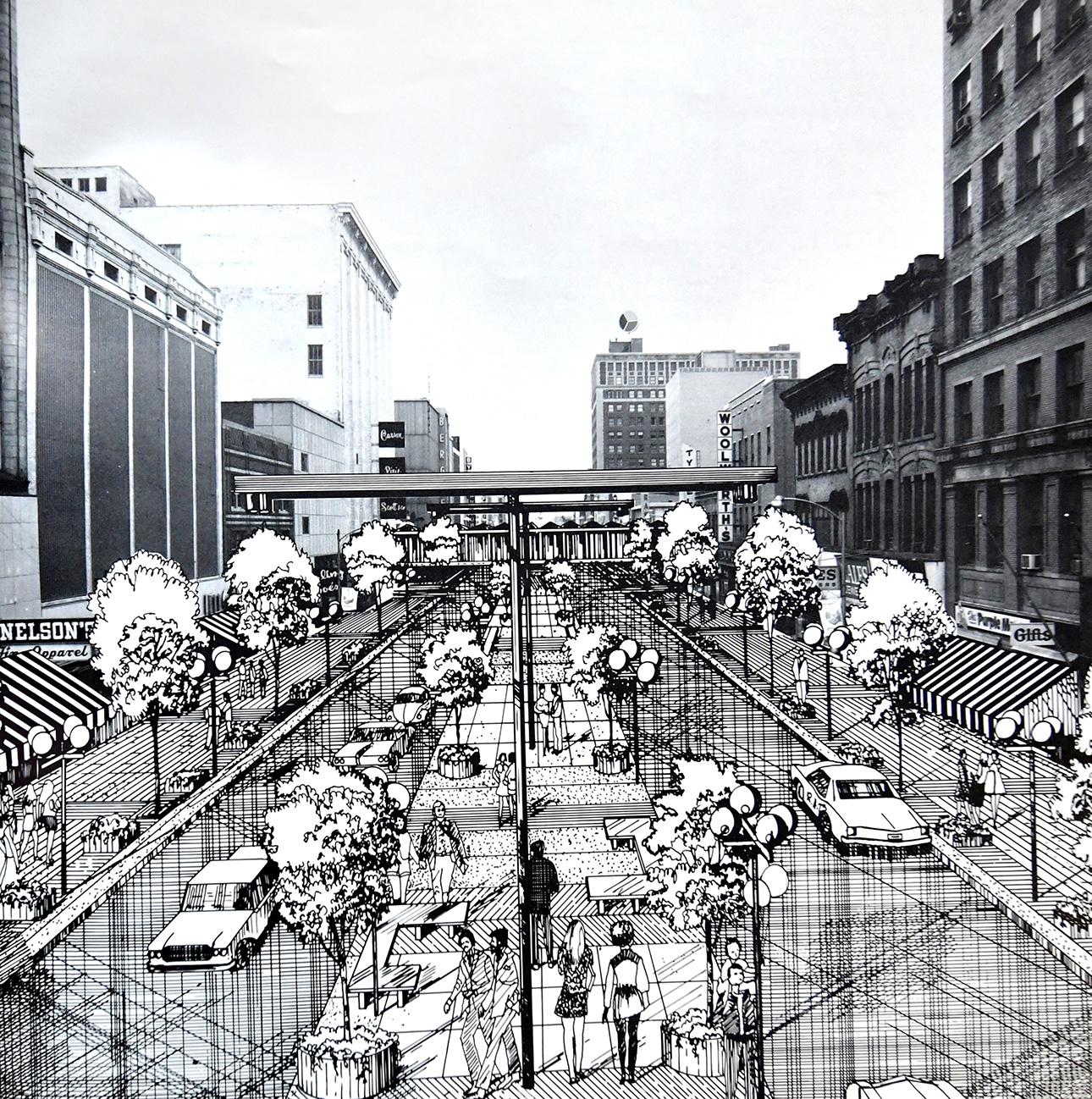

The Civic Center was its most notable offspring, but there were other defining projects for which the noted architect Angelos Demetriou planted the conceptual seeds: the Twin Towers, Fulton Plaza, the city’s RiverFront, the renovation of the Hotel Pere Marquette, the museum block and the late, great River Station, the “destination restaurant” that put Peoria on the culinary map in a way it hadn’t been before.

It changed everything, said retired state legislator David Leitch. Had Demetriou never entered Peoria’s orbit, Downtown today might well be “dead as a doornail,” he said. “There’d be no reason to go there.”

That’s where Downtown was heading in 1973.

‘Everything had to be beautiful’

Leitch, now 74, was there for all of it — indeed, at the very center of it, first as the City Hall reporter covering the story for the local daily newspaper, before being hired away to become president of the Downtown Development Council, the not-for-profit group of business leaders who spearheaded the private-sector side of Downtown’s reinvention. “I loved writing about it but the chance to do it really appealed to me,” he said.

‘Without beauty, a city has nothing to keep you’ — Angelos Demetriou

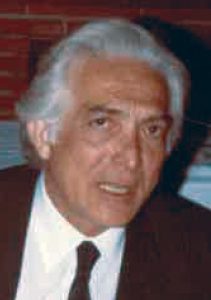

It has been 50 years since Demetriou, then 43, was hired in Peoria to help turn around what then was widely acknowledged as a dying downtown.

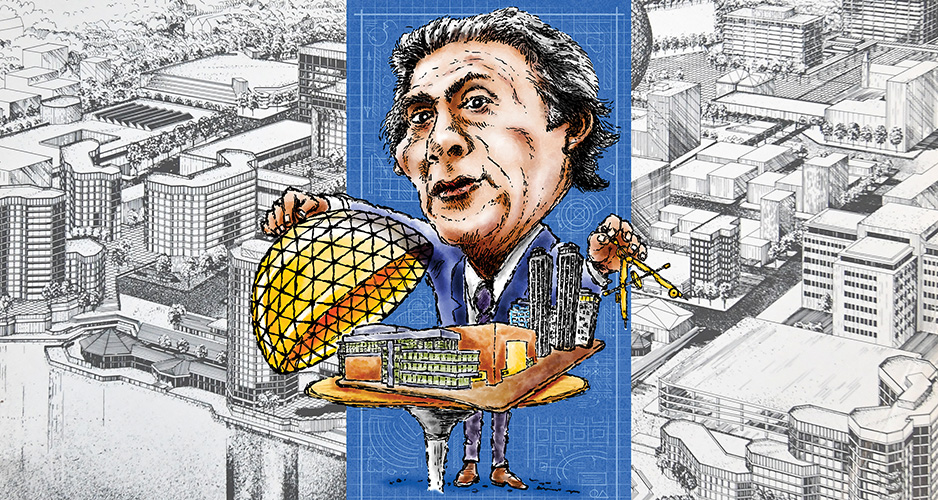

Part architect, part philosopher, part poet, the Cyprus-born Demetriou cut a striking figure between his silver mane of hair and his elegant, almost regal bearing. After cutting his teeth at the renowned Greek engineering and architectural firm Doxiadis, Demetriou found himself in America’s capital in an office off DuPont Circle, building his own global practice with projects across Europe, the Middle East and many major American cities, from Minneapolis to Miami.

“He was something else,” said Leitch. “He used that flamboyant side to conceal his street smarts.”

He recalls a Demetriou who was “the right guy for the job,” a professional of great precision, from his urban designs down to the hardboiled egg — “exactly three minutes” — he routinely ordered for breakfast.

“Everything had to be beautiful,” said Leitch, something Demetriou made clear in a memorable interview with the Journal Star.

“We have accepted a demotion in our lifestyle. The primary criteria have become speed and efficiency,” Demetriou said then. “Without beauty, a city has nothing to keep you … Only beauty remains active.”

At the time, those words touched a chord, Leitch said. “People had a lot of excitement about the Downtown then.”

‘The downstate capital of Illinois’

It wasn’t just Demetriou’s doing, of course.

Peoria was very much a headquarters city then, between Caterpillar, Central Illinois Light Co., Midwest Financial Group, Bergner’s, etc., with leaders willing to wield the clout they had. Specifically, there were forceful personalities such as bank president David Connor, CILCO CEO Harry Feltenstein and local industrialist Lew Burger. On the public side, there were former Mayor Richard Carver and a capable Council.

“With a strong mayor and council, and a strong private sector, and a strong plan like Demetriou’s, to me that’s a recipe for getting things done,” said Leitch. “I think the proof is in the pudding.”

Such was that group’s confidence that they didn’t flinch at bringing in world-class talent — first Demetriou, then Philip Johnson, winner of the first Pritzker Prize for architectural achievement, to do the Civic Center.

Connor in particular was devoted to raising Peoria’s game. “His vision was to make Peoria the capital of downstate Illinois,” said Leitch.

As for Carver, he “was — is — the greatest salesman that ever lived, and the most optimistic. Bombs would be exploding left and right, and ‘There’s no problem, I’ll take care of it,’ recalled Leitch. “And he would.”

Other plans have come and gone in Peoria because “they didn’t have a leader like Carver, and they didn’t have a leader like Connor,” said Leitch. “You put the two of them together, and there was a lot of power there.”

No miracle, ‘just a helluva lot of hard work’

If Demetriou was the dreamer with a dose of common sense about how to get things across the finish line, Connor was the hard-charging driver who wasn’t about to let the plan fail, and Carver the hard-eyed pragmatist.

“We have spared no efforts in creating our report, but it will be a failure to dwell on graphics, designs and words,” Demetriou said at the time. “Our primary concern now must be implementation, where we go from here.”

“Everyone seems very excited and enthusiastic, but the test is not how pretty the drawings are,” added Carver. “We cannot spend public monies until we are reasonably assured of a respectable return on investment.”

“Demetriou was the guy who lit the fire. Fundamentally, the idea of the Civic Center was his,” the 85-year-old Carver says today from his Sarasota, Florida home. But “he was the idea, not the doer.”

Ultimately, “there is no such thing as ‘one person did it,’” concludes Carver. “It happened because a very small group of people just said, ‘We’re going to make it happen no matter what.’ … You can look back and say it was a miracle. It wasn’t a miracle, just a helluva lot of hard work.”

Bumps along the way

Reality does have a tendency to intrude, of course. Not every prominent person and organization in town was on board. Cost estimates soared on Demetriou’s 31 projects — 10 public, 21 private. The first iteration of the Civic Center, which has undergone reinvestment and expansion since, ballooned from $35 million to $62 million, almost $190 million in today’s dollars, even after substantial cuts were made.

The City Council decision in 1976 to create a new tax to fund the Civic Center squeaked by on a 5-4 vote. The conventional wisdom was then and remains today that if the whole thing had gone to public referendum, it would have been defeated.

Today, Carver looks back at that vote and the Civic Center that resulted from it as, to that date, “the most important thing Peoria had done, maybe ever.”

‘This is not just a typical Midwestern city … It’s one of global importance’ — Angelos Demetriou

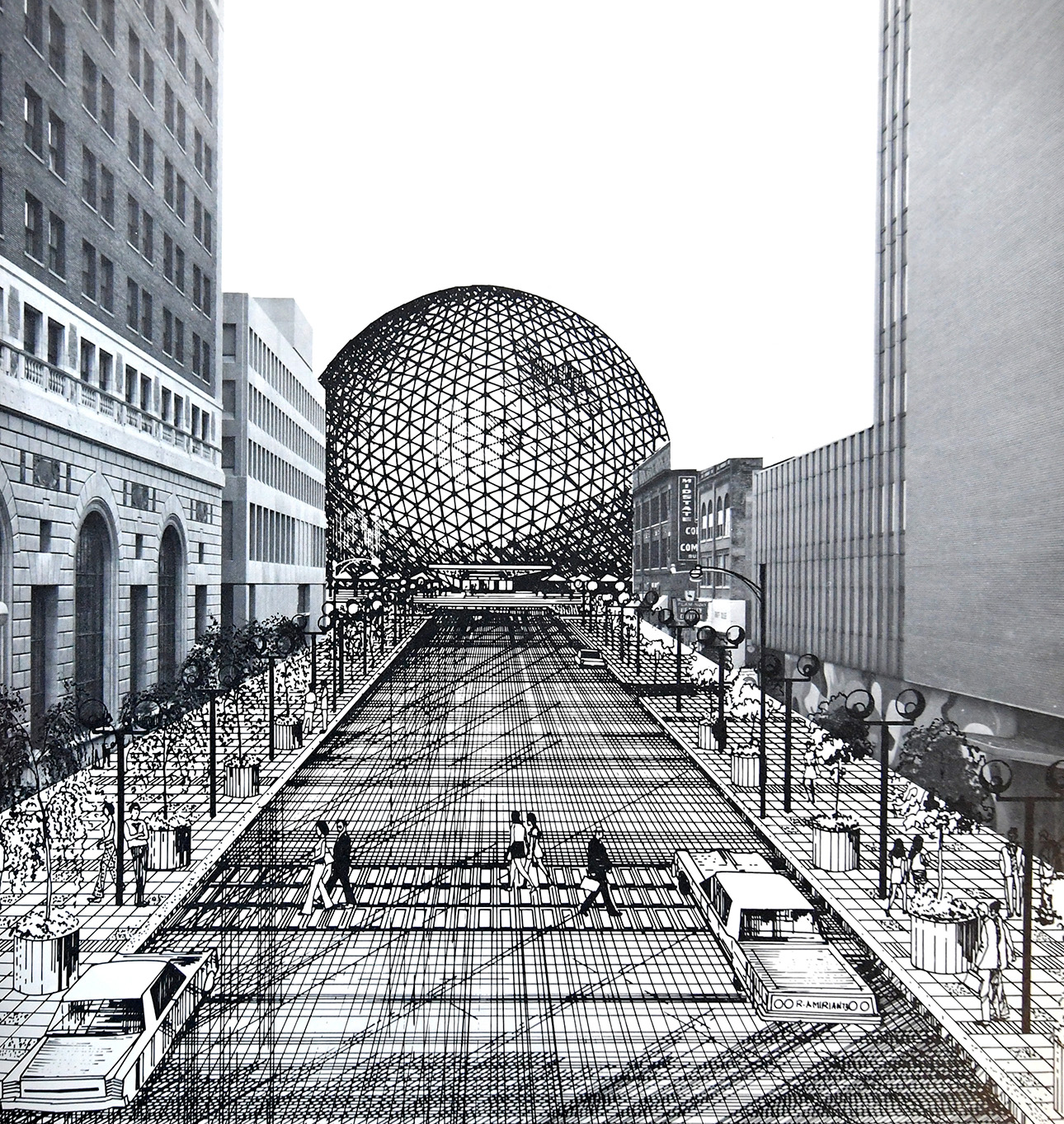

No one who takes that many swings hits every pitch, of course. The enclosed shopping mall that was a key component of the Demetriou Plan never broke ground, which remains a Carver lament, especially after he had lined up the urban renewal pioneer Jim Rouse, who rescued Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, to oversee it. The RiverFront has its stages and festival lawn but not quite the amphitheater and lagoon Demetriou envisioned. No new City Hall was constructed. Demetriou drew up a geodesic dome for the Civic Center, but Philip Johnson had other ideas. The boulevards and high-rise residential towers promising up to 1,000 units for 3,500 Downtown residents never materialized.

“The Civic Center exhausted people,” recalled Leitch, who described Demetriou as “happy at what had been accomplished but disappointed by the opportunities that had been lost.”

For his own part, near the end of his relationship with Peoria, Demetriou acknowledged that “there are still things to be done. But you have now created the assurance that, yes, there is a downtown … I always remember you, I miss you, I cherish you … I envy you for what is ahead. And, I bless you.”

Angelos Demetriou died, age 79, in 2009. There were obituaries for the “internationally known architect, city planner and urban designer” in the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Post, in which his Peoria work merited a mention.

“This is not just a typical Midwestern city,” Demetriou once said. “It’s one of global importance, with people of enormous talents and enormous egos and pride.”

It was the kind of affirmation that leaders of the era had yearned to earn.

When the Civic Center opened in June 1982 with a concert by Kenny Rogers, Carver sensed immediately that something significant had been accomplished.

“I wanted to excite people. I wanted people to think about not where we were but where we were going,” he said. “When I left Peoria in 1984, I couldn’t have been more pleased. Peoria had completely changed,” with a new attitude that the city could “do the things we needed to do to get things done.

“My goal was to get the city standing tall. For a time, it did.”