One of the finest, most innovative timepieces in the land was once made in Peoria

It wasn’t just any company.

Indeed, the Peoria Watch Company became “the story of success and failure followed by success and failure; the story of embezzlement … and jail sentences; the story of broken agreements and lawsuits; the story of a ‘mysterious and curious’ factory fire,” the historian Eugene T. Fuller wrote. It would make way for a horological school, “followed by a watch tool and eventual bicycle manufacturer, then the corn popper and coffee roaster company that ended up making automobiles — finally to be absorbed in the name and cause of higher education!”

An inauspicious beginning

The story begins in 1864 with the establishment of the Newark Watch Company of New Jersey. The company began making watches “of English design” but discovered that “watch making was easier said than done.”

After manufacturing about 3,000 watches, Newark “fell behind” the demand, and the company folded and was sold in 1869, wrote Henry G. Abbot in his early chronology, The Watch Factories of America.

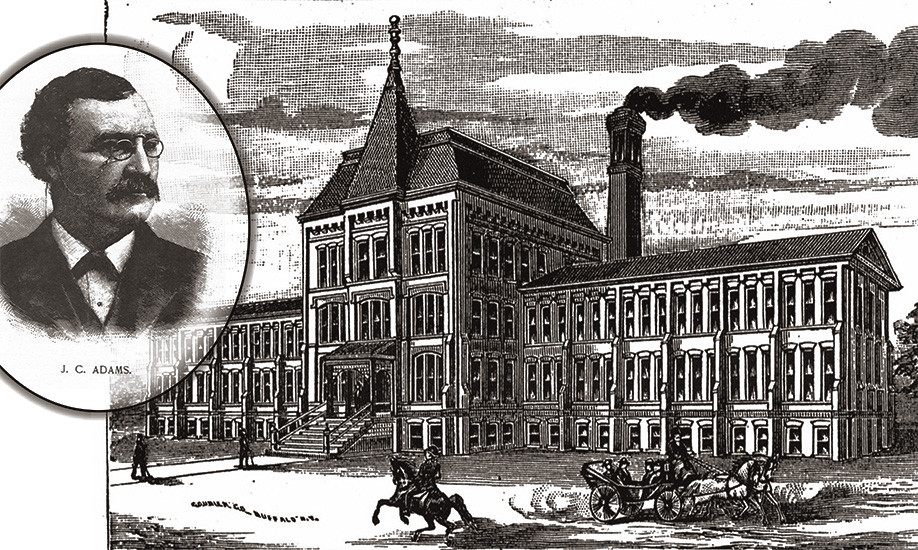

About the same time, real estate developer Paul Cornell, who had purchased land in Chicago after the Great Fire, had decided to build a factory on property he was developing in the Hyde Park neighborhood. He approached one of the pioneers of American watchmaking, John C. Adams, who had been instrumental in establishing the National Watch Company in Elgin, Illinois and the Springfield Watch Company (later Illinois Watch Company) in Springfield. Adams suggested purchasing the Newark Watch factory.

Cornell set aside 30 acres and invested $75,000. The new building was completed in February of 1871, and all the machinery of the Newark Watch Factory was moved to Chicago.

But by 1874, “Cornell was looking for relief, too,” Fuller recalled. He moved the factory to San Francisco, intending to exploit the cheap Chinese labor there. Alas, the construction of the transcontinental railroad prompted much racial prejudice. White workers “threatened to strike if Chinese were hired and so the company was forced to abandon this idea,” wrote Fuller. Only a few watches were finished in San Francisco before the operation was moved to Berkeley in 1875. The California Watch Company declared bankruptcy and closed in 1876.

Changing time zones again

In Fredonia, New York, the Howard brothers, Edward and Clarence, were corporate opportunists. They set up a business purchasing watch movements from various companies and selling them at retail establishments under the name “The Independent Watch Company.”

In 1880 they decided to try their hand at manufacturing, forming the Fredonia Watch Company. The machinery, from defunct companies in California and Illinois, was on the move again. The Howards were progressive in adopting the non-magnetic balance springs of Charles Auguste Paillard, but consumers weren’t warming to watches sold through retail outlets, and Fredonia floundered.

In 1883, John C. Adams was again enlisted to assist the Howard brothers. He recommended moving the factory to Peoria. The endeavor was encouraged by an organization called the “Peoria Improvement Association.” Contractor John L. Flynn was granted the construction contract for $17,500.

The Chicago Inter Ocean reported in December of 1886 that the Peoria Watch Company would manufacture “quick-train” — faster beat — “railway watches” with 15 jewels, “the only anti-magnetic watch manufactured in this country; escapement of aluminum bronze, which cannot be magnetized.” The Peoria watches used Paillard’s patented non-magnetic alloy. Its main ingredient was palladium, not aluminum.

Electricity was coming into widespread use, and the balance springs, thinner than a human hair, were extremely susceptible to the influence of magnetos used in motors of all types. Paillard’s invention was even endorsed by Thomas Edison as an infallible solution to the erratic performance caused by magnetism.

In 1888, the Peoria watches were said to carry a two-year warranty. Fuller stated: “I am convinced that the Non-Magnetic watches by Peoria (were) the best products the company ever manufactured.” The escapement of the movement was said to be made of the same alloy used by the most prestigious watch manufacturers in Switzerland.

A generous benefactor

The Peoria operation began with a capital investment of $250,000 and was to be built on Peoria’s West Bluff, on property donated by Lydia Moss Bradley and a few others. Bradley specifically stipulated that the land be designated for a watch factory. Elisabeth Griswold also donated land, and this was where Clarence Howard built his residence.

The Sanborn Insurance Maps of Peoria from the Library of Congress pictured the factory in 1891 between Bradley and Fuller Streets. The storage, gilding and engraving departments were on the first floor, the finishing and adjusting operations on the second floor. The east wing housed the machine shop and train room, where the wheels were made and teeth cut. The jeweling department was on its second floor. The Peoria operation had about 90 employees producing 30 movements per day by the first of June 1887.

Estimates had the company realizing $150,000 in revenue from the watches produced in that first year. The first complete watch manufactured in the Peoria factory, serial number one, was completed sometime in late 1886 or early 1887 and presented to a major businessman and investor named Joseph B. Greenhut, a local railroad executive, banker and businessman of considerable wealth. With Adams’ influence, the factory drew on the expertise and talent of both the Elgin and Illinois watch companies.

‘The Peoria Watch’ makes a name for itself

By May 1 of 1886, the watch factory was being called “the pride of the West Bluff” by the Peoria Saturday Evening Call. Part of Adams’ strategy for the merchandising of the product was to advertise and market to the nation’s growing railroad industry, where keeping time was essential to safety.

In 1887, the “Peoria Watch” was being advertised as the “official watch of the Santa Fe Railway.” It also had been adopted by the Wabash, Denver & Rio Grande and Southern Pacific railways. “Any railroad man who has ever used ‘The Peoria Watch’ will never use any other,” it was said at the time. This was still 10 years before Webb C. Ball proposed a specific standard for railroad timepieces used in the U.S.

Watch factories in the 19th century usually produced movements that were sent directly to jewelers, who offered them to clients and fitted them to a variety of cases with everything from base metal to solid gold or platinum. Because the watch movements were visible to customers at the time of purchase, they were made with eye appeal, employing elaborate damaskeening, or decorative patterning. The higher-grade Peoria watches, many collectors believe, were among the most beautiful.

Headwinds

By 1899, most railroads were requiring watches for trainmen and yardmasters to pass a strict inspection requiring, among other things, at least 17 jewels. The Peoria watches had, at most, 15 jewels. The Decatur Daily Review reported on Nov. 25, 1899 that the Peoria watches were among those not accepted by the Wabash line.

Though the Peoria watches were an accurate and beautiful work of art, major watch companies such as Elgin, Waltham, Illinois and Hamilton had developed watches that were smaller, lighter and of higher jewel count. The basic design of the Peoria watch had not changed since it was first produced in Newark, New Jersey in the 1860s.

By 1888, the Peoria Watch Company was said to be in trouble “on account of lack of funds.” The year before, the secretary of the company, J. Finley Hoke, had been arrested for embezzlement. The watch company was one of his victims.

The daily production rate at the factory was then only 20 watches. Elgin, by comparison, was producing 1,400 watches per day. When compared to 11 other watch companies, the Peoria factory came in last. Yet Clarence Howard was still buying real estate in Peoria, and the Peoria watch was still being touted as the official watch of the ATSF Railroad.

Jewelers continued to advertise their stock of Peoria watches for several years after the factory closed in about 1888, while touting their superior quality.

Still keeping time, and value

Ultimately, the factory was taken over by the Parsons Horological Institute, said Fuller. The watch-making school of J.R. Parsons, “a practical jeweler of La Porte, Ind.,” was moved from La Porte to Peoria in about 1892 and took up residence at Bradley University. With some 150 students then in attendance, the main building was gutted by fire in 1896.

The typical pocket watch of the 19th century was made to last indefinitely, and Peoria watches were no exception. They were precision instruments and works of fine industrial art in their day. They are still considered collectors’ items, commanding fairly high prices at auction.

Information for this story came from correspondence with historian Eugene T. Fuller of Sugar Land, Texas, and from Henry G. Abbott’s book, The Watch Factories of America.