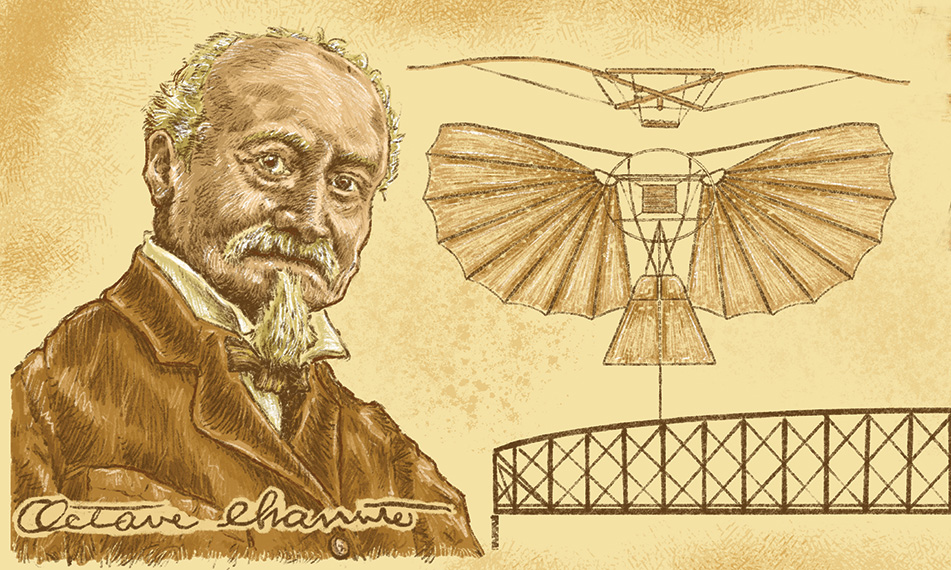

Peorian Octave Chanute was a significant influence on the Wright brothers and that famous first flight

The letter, dated May 13, 1900, was astonishing in its directness and abruptness. It lacked even the customary salutation.

“For some years,” it began, “I have been afflicted with the belief that flight is possible to man. My disease has increased in severity and I feel that it will soon cost me an increased amount of money, if not my life.”

The author: Wilbur Wright.

The recipient: Octave Chanute.

It was at the latter’s modest, calf-high Springdale Cemetery headstone that I recently stood, pondering the serendipity of time and place and Chanute’s pivotal role in the first successful, powered and manned flight.

In 1857, Chanute married Annie Riddel James of Peoria, Illinois. The family lived here for seven years. They now rest for eternity at Peoria’s Springdale, where on the day of my visit, 16 family markers defined a graceful granite arc in the Mt. Repose section, directly behind the imposing Salzenstein/Lehmann mausoleum.

But for the whims of fate, Chanute, a wealthy Chicago businessman, might never have set foot in America, let alone Peoria.

Born in 1832 in Paris, France, he immigrated to the United States at age 6 when his father accepted a position as vice president and history professor at Jefferson College, north of New Orleans.

Though he was precocious from the beginning, few could have foreseen his capacity to shape destiny.

By age 17, the New York-educated prodigy had become a consulting engineer. His brilliant engineering triumphs included the design and construction of bridges and his plans for the Chicago and Kansas City stockyards. His first bridge project was Peoria’s Illinois River rail bridge. He was the architect behind the Hannibal Bridge — the first to cross the Missouri River — in 1869, as well as a score of others.

His proprietary system for pressure-treating rail ties and telephone poles with creosote is used to this day. The tenacious, intense Chanute also introduced the railroad date nail to the United States, a system of recording the age of railroad ties by date stamping the heads of nails.

Chanute worked his way through the ranks in the railroad business, from chainman (surveyor) for the Hudson River Railroad to railroad civil engineer to chief engineer of the Chicago and Alton Railroad. Chicago was home for the last 21 years of his life.

In his twilight years, Chanute developed a consuming interest in gliding and aviation experiments. This was a risky stance in an academic environment that largely ridiculed and belittled the idea of manned flight. Most scientists of the day sniffed and recoiled at such a notion.

But Chanute’s seminal 1894 book, Progress in Flying Machines, was considered the definitive source for aviation wisdom. Those on the threshold of powered flight — among them the Wright Brothers — eagerly petitioned for Chanute’s attention and counsel. So keen was the interest of both parties that Wilbur Wright’s first letter opened a veritable flood of correspondence, generating hundreds of letters over a decade.

As prolific and voluminous as the Wright brothers’ letters to Chanute were, they did not retain copies of their correspondence. Chanute, however, seized every scrap. His engineering precision and obsession with detail — and perhaps his sense of a nascent, world-changing event — allowed historians to assemble a remarkably accurate record of the development of flight. These documents are part of the permanent collection in the Library of Congress.

Imagine Chanute’s passion in his role as friend, mentor and confidant of the Wright brothers. His participation was vigorous, though vicarious. At age 64, he was considered too old to fly himself. Yet beginning in the summer of 1896, his assistants tested gliders of his own design.

These experiments were carried out at Dune Park, near Gary, Indiana, on the southern shore of Lake Michigan. Eschewing secrecy, they were very public, and equally successful. More than 700 glider flights yielded a treasure trove of information, unlocking vexing mysteries of the calculus of flight.

The aerodynamic riddles Chanute solved were graciously shared with the larger aviation community. For example, his knowledge of bridge trussing was deftly applied to glider construction. He pioneered the strut-wire braced wing structure, which became the standard in powered biplane aircraft.

Unselfishly, he sought no patents on his work. Chanute’s recommendations for an ideal place to test aircraft led to the Wrights’ selection of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, for their historic flight trials. He visited them at their Kitty Hawk camp and sent his own assistants to work with them.

Chanute’s openness and sharing attitude are evident in this passage from Progress in Flying Machines: “Let us hope that the advent of a successful flying machine, now only dimly foreseen and nevertheless thought to be possible, will bring nothing but good into the world; that it shall abridge distance, make all parts of the globe accessible, bring men into closer relation with each other, advance civilization, and hasten the promised era in which there shall be nothing but peace and goodwill among all men.”

Chanute became a friend and financier of several other early pioneers of flight. Among them were Louis Mouillard of France, Otto Lilienthal of Germany, and Samuel P. Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a tireless flight experimenter in his own right. Chanute was the selfless facilitator, the ardent catalyst who brought together disparate individuals and interests to help legitimize and orchestrate the dream of flight.

Chanute died in 1910. Wilbur Wright delivered his eulogy, saying of his friend, “His labors had vast influence in bringing about the era of human flight … No one was too humble to receive a share of his time. In patience and goodness of heart he has rarely been surpassed. Few men were more universally respected and loved.”

No doubt we can credit Annie Riddel James for Chanute’s Peoria connection. How he came to be interred at Springdale — along with some 78,000 other souls — is certainly a quirk of romance and geography.

But to have such a visionary memorialized in our midst is a benefit of incalculable value, sometimes revealed in the most surprising ways. As I stood on the sodden Springdale turf ruminating on the meaning of it all, a passenger jet slipped through the overcast sky above.