A little known but sensational part of Peoria’s history is that the city hosted a popular Wild West show in the early part of the 20th century. Though not the largest, it was certainly the finest quality show of its kind in America.

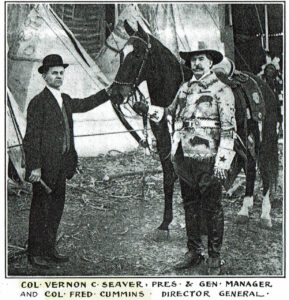

In 1904, Chicago restaurant entrepreneur Vernon Seaver sailed his yacht down the Illinois River looking for a passage from Chicago to St. Louis, intending to establish a practical route to ferry passengers to the St. Louis World’s Fair. Seaver had pioneered the development of silent film theaters in Chicago and was an entertainment business visionary.

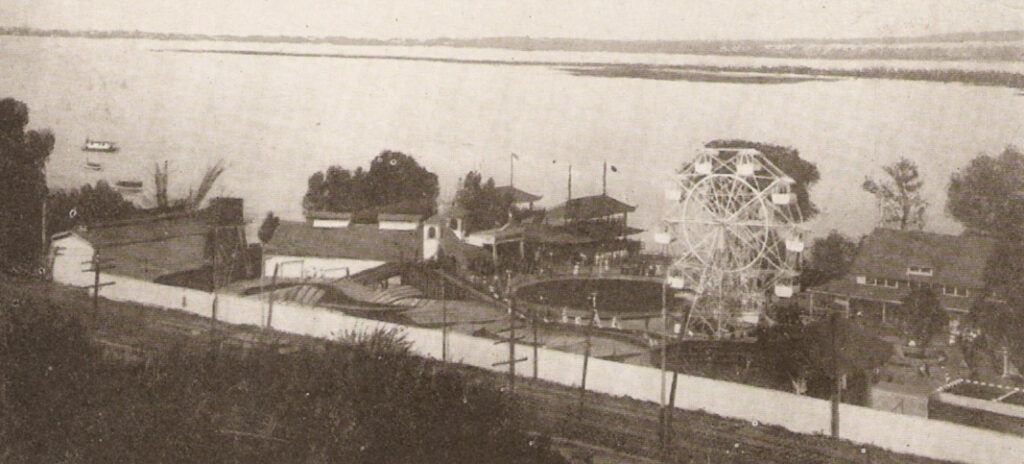

What he found, instead of a route to St. Louis, was an ideal location for an amusement park in Peoria. With the financial assistance of the Central City Street Car Company, Seaver opened his park in 1908 at a site on Galena Road north of Peoria along the Illinois River. He called it “Al Fresco Park.” It was serviced by streetcars and riverboats.

In its first year of operation, Al Fresco featured an attraction called “The Lone Bill Wild West.” Wild West shows were enormously popular at the turn of the century, with a great deal of publicity surrounding the myths of the Old West. The enormously popular Lone Bill Show not only played at Al Fresco, it toured throughout Illinois.

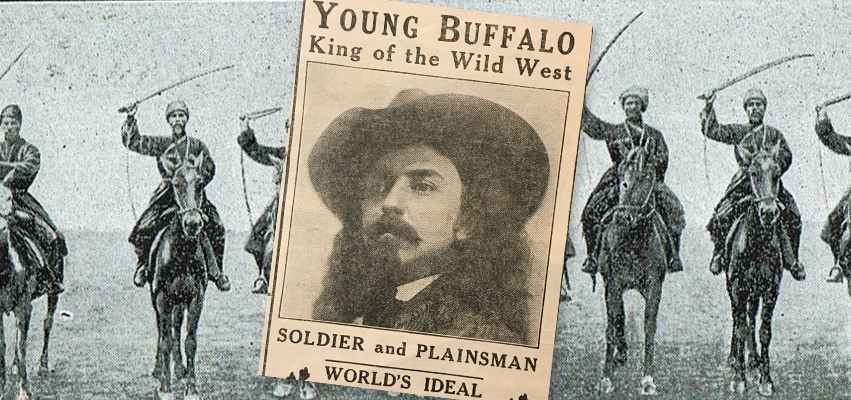

In 1910, the name was changed to “The Young Buffalo Wild West,” taking the name of a popular melodrama of the time, and the show traveled widely throughout the United States. When Seaver partnered with showman Frederick T. Cummins in 1912, the consolidated show became “Young Buffalo’s Wild West and Col. Cummins Far East Show.”

In time the show came to include cowboys and cowgirls from Texas, Montana and Oklahoma — bronco busters, horse wranglers, plainsmen, Peruvian gauchos, and Mexican vaqueros and rurales. Cummins’ “Far East” part of the performance, as advertised, was made up of an impressive cast of exotic performers — Russian Cossacks, Bedouin Arabs, a Japanese troupe, Berber Arabians, Indian “Cengalese,” wild Australians, and “Meori” Spearmen.

In time the show came to include cowboys and cowgirls from Texas, Montana and Oklahoma — bronco busters, horse wranglers, plainsmen, Peruvian gauchos, and Mexican vaqueros and rurales. Cummins’ “Far East” part of the performance, as advertised, was made up of an impressive cast of exotic performers — Russian Cossacks, Bedouin Arabs, a Japanese troupe, Berber Arabians, Indian “Cengalese,” wild Australians, and “Meori” Spearmen.

The show always opened in April or early May, usually following a street parade through Peoria that wound its way from Southwest Adams Street to Cedar, to Warner, to First, to Franklin, to Jefferson, to Hamilton, back to Adams and on to the show grounds at Lake View Park (Adams and Garden streets). From 1910 through 1912, the show pitched its tents at this location. In 1913-14, the opening performance took place on a lot next to a North End ballpark, four blocks from the Illinois River.

The Young Buffalo Show advertised itself as up-to-date entertainment. Seaver consistently and enthusiastically sought to expand the show with new acts and bigger performances. In 1910, he entered into a business relationship with William P. Hall, of Lancaster, Missouri, a legend in the circus business and one of its biggest suppliers of equipment and Wild West stock. With Hall’s assistance, Seaver gained access to an enormous variety of show stock and exotic animals.

The Young Buffalo Show started in 1910 with 200 performers and attaches and more than 150 range horses, broncos, burros, Indian ponies, oxen, draught horses and wild steers. By 1912, the show employed 482 people, along with 225 horses and a herd apiece of elephants and camels. In 1913, the show advertised an arena seating “something over six thousand” (a later report said 10,000).”

This enormous open stadium had to be laid out, constructed, torn down and moved on a daily basis. Beyond the U.S., it was said to be the only Wild West show that had toured successfully through Canada.

Besides the main show, Young Buffalo employed vendors “from all nations” on the midway, along with two sideshows filled with “freaks of nature” and a minstrel band. Inside the sideshow tent in 1911 was a mind reader, a bagpiper and Scottish dancer, an oriental band, a magic and Punch act, Mlle. Alvora and her oriental dancing girls, Latina and her snakes, Mr. and Mrs. Carlos and their “feats of strength,” “whirlwind dancers,” a tattooed lady, Spanish dancers, and “Yellow Boy, the sword swallower.”

The arena show was structured around Old West themes such as “The Siege of the Alamo,” “Peace and War,” “The Attack on the T. B. Ranch,” “Shooting up the Town,” and the tournament presentation, called “Civilization.” In 1912 the show featured an overland coach holdup, a team of 20 oxen, a Pony Express mail rider, and a prairie schooner attacked by a band of Indians.

A professional actor played the part of Young Buffalo. Seaver’s own son, Vernon Seaver Jr., portrayed Young Buffalo Jr. to appeal to the youngsters. The roster of the Young Buffalo Show then included 75 cowboys and rough riders, up to 18 cowgirls, and 60 Native Americans from five different tribes.

The show boasted some of the greatest names in the business — expert marksmen Annie Oakley, Captain Adam H. Bogardus, Curtis Liston and silent movie star Tom Mix. Others took part in traditional rodeo events such as rope tricks, bronco and steer busting, trick riding, horse racing and bull dogging. There were many champion performers — names that are mostly lost to us now — such as cowgirls Prairie Rose Henderson and Margaret Norwood, and cowboys Ambrose Means, Buffalo Vernon, Fred Cox, Arizona Joe, Montana Jack and Colorado Cotton.

Novelty acts also were featured — Maude Burbank and her famous horse, Dynamo; Marion and Billie Waite, expert whip crackers and boomerang throwers from Australia; and “Little Billiken,” billed as the “midget elephant.” Notable Native American players from South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation were featured in various acts such as the Indian war dance. The company included chiefs such as Red Shirt, Flat Iron, Painted Horse, Good Face, Thunder Bird, Charlie Black Horse, etc.

The end of the Young Buffalo Show came in 1914, despite press reports that business had been good. The news had not been good for the entertainment business in general. The Buffalo Bill and Pawnee Bill Wild West Show, the largest show of its kind in America, failed in 1913 and broke up.

In 1914, Vernon Seaver’s personal life was unstable. The Wild West show had been his pet project, and he had committed a fortune to its development. He had apparently overextended himself financially, with other business ventures as well.