Assistant professor of economics and director of the actuarial science business program at Bradley University

Welcome back to Peoria Magazine’s Econ Corner, a recurring feature in which we pose questions to experts about various economic issues and how they affect our lives and careers here in central Illinois.

Doing this month’s Q&A is Chigozie Andy Ngwaba, PhD, assistant professor of economics and director of the actuarial science business program at Bradley University. He joined BU’s Department of Economics in the fall of 2020. Prior to that, he worked in the corporate actuarial field, performing retirement plan pricing and profitability analysis.

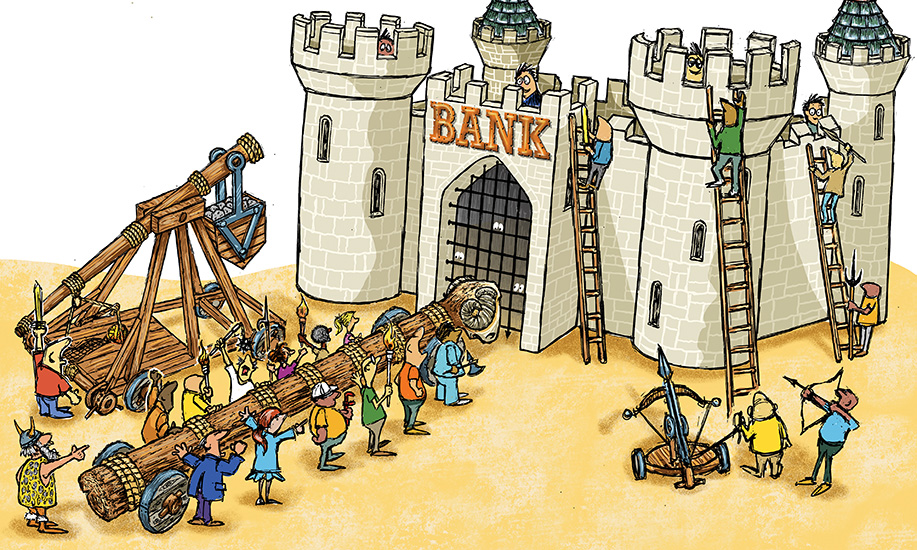

Peoria Magazine (PM): In the wake of the Silicon Valley Bank failure, then Signature Bank, then First Republic Bank’s troubles, then Credit Suisse … How is it that the widely acknowledged mismanagement at one not-super-large bank starts knocking down dominoes across the globe so that markets tumble and there’s now talk of potential recession? How does that happen?

It is essential to strike a balance between preventing a systematic failure and avoiding … moral hazard

Chigozie Andy Ngwaba (CAN): In the banking sector, perception is critical. If people think a bank is weak, the news will spread fast, which may lead to a run on banks, and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Note that the run on the banks in 2023 is different from the past. Today, individuals can quickly transfer money from one bank to the other online. Similarly, a bank failure can lead to a loss of confidence in the entire financial sector, creating a domino effect internally and globally.

The financial system is interconnected, which means a failure can lead to a contagion that can spread far and wide, especially when banks face the same risk, in this case, interest rate risk. In the case of Credit Suisse, they had problems prior to the recent bank failures, which brought them into the limelight.

PM: Silicon Valley Bank was the victim of a classic bank run, with panicked depositors pulling their money out beyond the bank’s ability to handle those withdrawals. Was that kind of response warranted in any way, or was it an overreaction that itself became the problem? With the FDIC insuring deposits up to $250,000 — and now beyond — why panic?

CAN: Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was in a unique situation because it is a bank for start-ups and fully operating companies. Unfortunately, this means the average account was more than $250,000, fueling the panic.

The run on SVB was not an overreaction. If people did not react the way they did, it would have just taken more time for the inevitable. The tight market conditions meant these companies needed to withdraw more and more cash, which made SVB close out on the government treasuries, which were now worth less because of the higher interest rate.

PM: The White House moved very quickly to bail out a couple banks and their customers. In your view, is it better in the long run for taxpayers to come to the rescue of the culprits and head the “risk of contagion” off at the pass, or should those responsible be left to suffer the consequences of their own bad decisions? To what degree is a “moral hazard” situation being created here?

CAN: Regulators moved quickly to bail out the customers because allowing the bank to fail completely would have created a systematic risk that would have affected the global economy.

Bailing out the banks regularly would create a moral hazard situation that incentivizes them to take more risks. The reasoning behind this is bank executives know they will benefit from profits, and taxpayers will bear the losses. It is essential to strike a balance between preventing a systematic failure and avoiding the creation of moral hazard. This can be done through a mix of banking regulation and oversight.

PM: The banking crisis has initiated a national debate, often between those of differing political persuasions, about whether our financial institutions need more oversight or less. Is there too much government regulation, too little, or is it just about right? Is a Dodd-Frank Act helpful or hurtful in avoiding situations like this one?

The problem with too much regulation is it can create a situation where U.S. banks are at a competitive disadvantage

CAN: Currently, the banking regulations in place are about right. We can observe this by how strong the big banks are. Companies that had accounts with the troubled regional banks moved their money to the big banks like JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America and the like. The problem with too much regulation is it can create a situation where U.S. banks are at a competitive disadvantage compared to their counterparts overseas. The most effective way of preventing this problem in the future is for regulators to perform more stress test accounting for high-interest rate scenarios.

I would say the Dodd-Frank Act has been helpful in avoiding situations like this. The act created stricter capital requirements for financial institutions engaging in risky behavior like derivatives. It also created a consumer protection agency.